The doorway: It’s a feature of any structure. Maybe it’s not where your eye goes first when you admire the architecture of a house or office building, maybe you don’t think about it much when you walk in or out. But doors, and the passages that support them, simply must be made right and installed correctly. In rough order, they must:

- be functional;

- look attractive;

- keep the internal environment in, and the outdoor elements out.

For UB’s new library, a well-made, long-lasting seal between the outside and inside is an essential part of the project. Not only do the front and rear entryways serve the critical function of human access, they also present the common challenge of how to keep the building warm or cool, depending on environmental conditions. Leaky windows, leaky doors―these are problems that keep architects and engineers awake at night.

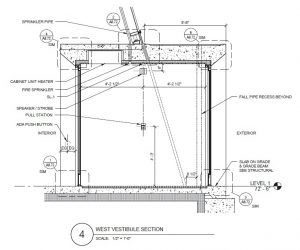

For this building―a re-skinned, rejuvenated facility created from the solid structure of the former library―the solution is a cube-like vestibule, located on both the front and rear sides. This clean, simple structure, made from cast concrete and surrounded by large glass panes, serves as an environmentally controlled break between outdoors and in. It’s lighted, ventilated, and fitted precisely into the overall structure of the building.

For this building―a re-skinned, rejuvenated facility created from the solid structure of the former library―the solution is a cube-like vestibule, located on both the front and rear sides. This clean, simple structure, made from cast concrete and surrounded by large glass panes, serves as an environmentally controlled break between outdoors and in. It’s lighted, ventilated, and fitted precisely into the overall structure of the building.

It’s that last piece―the precision of the layout―that stands out on this project: How did the builders make sure that the vestibules were positioned just right, so that the windows and their metal framing, plus the flooring and other integrated elements, could work together in harmony with the passageway? In other words, how did this enormous piece of concrete line up with its surroundings?

Darryl Richardson, project manager for the project’s principal contractor, Plano-Coudon Construction of Baltimore, has a straightforward answer:

“We drew it up. We talked a lot. We took measurements.”

Beyond correctly constructing the concrete forms for the in-place pour―in tight spaces only feet away from busy streets and in the midst of other heavy construction happening around the building―the difficult part of making the vestibule involved a channel that wraps around the top and sides of the piece. Richardson says this “thermal break” could not be cut into the passage after the concrete cured, because there is ventilation and lighting conduit, plus supportive rebar, built into the piece. Instead, the channels had to be part of the original pouring of the concrete.

This was not so difficult on the Maryland Avenue vestibule, Richardson explains, because on that side of the library the channel is a simple vertical element―it just had to be straight, level to the ground, and matched to the level window framing. Once the concrete was dried and the wood casting frames removed, workers installed the metal, glass and seals, creating a water- and airtight piece.

But the back side of the building proved to be more of a challenge. There, a glass and aluminum “curtain wall,” rising boldly from the ground to the roofline, sits at a steep pitch. The vestibule penetrates this wall near the Oliver Street side, again at an angle. At ground level, there’s a façade drain to keep water away from the wall, which sits at the bottom of a long, gradual hill.

But the back side of the building proved to be more of a challenge. There, a glass and aluminum “curtain wall,” rising boldly from the ground to the roofline, sits at a steep pitch. The vestibule penetrates this wall near the Oliver Street side, again at an angle. At ground level, there’s a façade drain to keep water away from the wall, which sits at the bottom of a long, gradual hill.

Richardson says there were many factors to consider for this passageway: how to establish a good seal; how to make the vestibule integral to the glass wall; how to site the casting so that the drain can do its job. For the engineers and builders, a leading concern was how to get the angle of the lapping channel correct. Again, this multi-ton structure was built in place; it could not be moved around or cut into if the angle wasn’t correct.

After days of consulting blueprints and conferring with the architects, engineers, and his own team of builders, Richardson says they made doubly sure that the channel angle was correct by marking the concrete form by hand.

“The window frames were right there, so we could use those as our guide,” he says. “It worked out well.”

Now, weeks after the concrete was poured and cured, both vestibules are fully exposed as workers finish the lighting and ventilation pieces. The framing is tightly wedded to the concrete, and it should last for years. A building that needs to be dry and quiet, plus cool in summer and warm in winter, should stay that way.

“It’s a finished look,” Richardson says. “It wasn’t an easy part of the project, but it was worth it.”