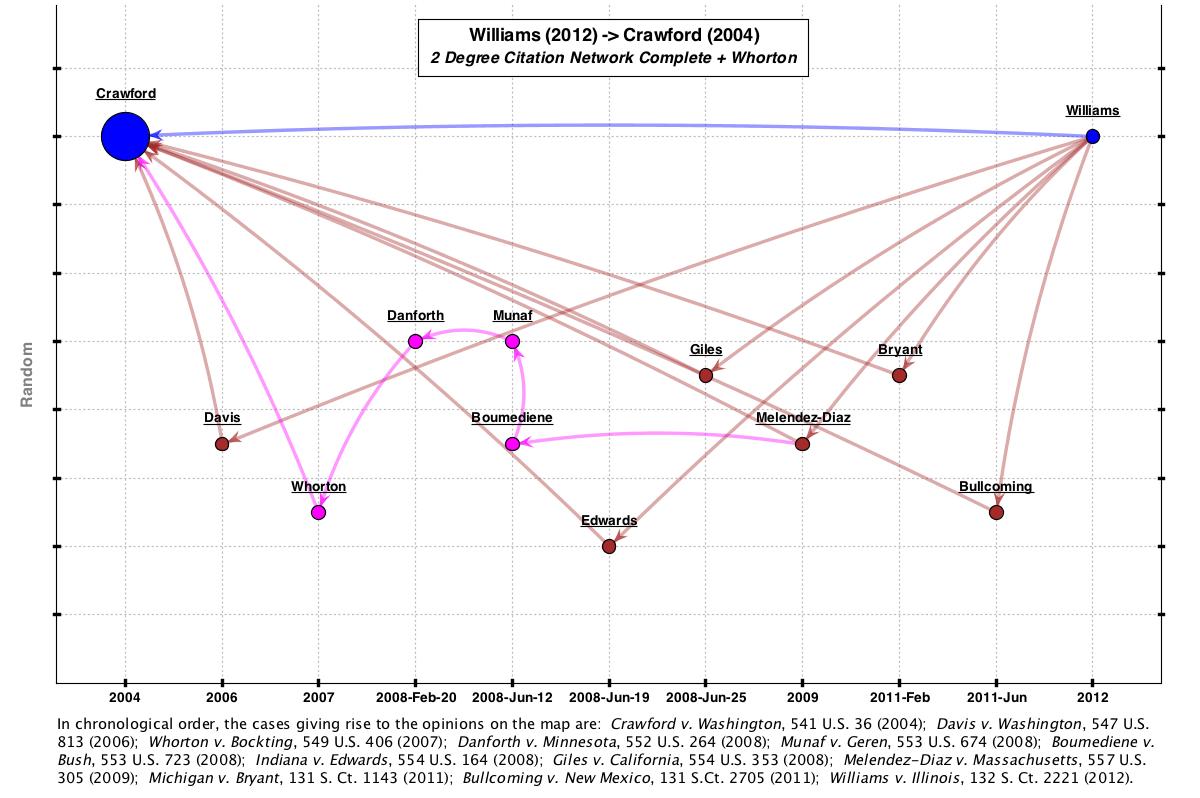

In celebration of Crawford v. Washington‘s 10-year anniversary, we’re looking at Supreme Court Confrontation Clause doctrine. In my last post, I generated a 2-degree citation network connecting the Williams v. Illinois (2012) back to Crawford. The 2-degree algorithm produced a network that included seven of the Court’s eight major post-Crawford rulings (as identified by Prof. George Fisher) and only included one case not apparently part of the main post-Crawford line. Although this network is relatively complete, the reasons for its under- and over- inclusiveness warrant further attention.

Let’s start with the under-inclusiveness problem. The 2-degree algorithm did not pick up 2007’s Whorton v. Bockting. This means that (a) Williams did not cite Whorton; and (b) no case cited by Williams itself cited Whorton. As it happens, there are also no 3- or 4-degree connections between Williams and Whorton. To link Williams and Whorton by citations actually requires 5 separate steps. Here’s what those steps look like (click for full-size with opinion links):

As shown by the pink line, the citation line from Williams to Whorton must pass through Melendez-Diaz (2009) to Boumediene (2008) to Munaf (2008) to Danforth (2008). Danforth finally provides a Supreme Court cite to Whorton.

So what’s the deal? Why doesn’t the Court ever cite to Whorton anywhere near its mainline Crawford cases? Here a simple explanation works: the only “Crawford issue” in Whorton concerned retroactivity. Specifically, Whorton unanimously held that Crawford did not apply retroactively. So once decided, Whorton had no bearing on the development of Crawford doctrine. There is no need to cite it anymore. Indeed, SCOTUS has only ever cited the case twice: once in a retroactivity case (Danforth (2008)) and once in a GVR arising out of Whorton itself.

Now let’s turn to the over-inclusivity problem. The 2-degree algorithm picked up Indiana v. Edwards (2008), a criminal case largely concerned with mental competency. The reason that Edwards shows up is because Justice Alito cited the case in his plurality opinion in Williams. Specifically, Justice Alito cites Edwards as one of a “steady stream of new cases in this Court” resulting from Crawford. To be honest, this cite is rather baffling since Edwards has nothing to do with confrontation.

To delve into this mystery, let’s look at Edwards. In his majority opinion in that case, Justice Breyer does very briefly cite Crawford while making a general point that the Court has generally “rejected an approach to individual liberties that abstracts from the right to its purposes, and then eliminates the right.” Breyer points to Crawford as an example of this general point (“although the Confrontation Clause aims to produce fairness by ensuring the reliability of testimony, States may not provide for unconfronted testimony to be used at trial so long as it is reliable.”). In context, this reference seems gentle dig at Justice Scalia who famously wrote Crawford, yet dissented in Edwards.

So why does Edwards subsequently get cited by Justice Alito in Williams? I have no real idea but am willing to hazard a wild guess. I’ll blame powerful search engines and imprecise argument. If someone — let’s say a clerk — was to search for SCOTUS cases that cited both cited Crawford and provoked a dissent from Justice Scalia, Edwards would come up. Since Scalia did not join the majority or plurality in Williams, this cite sort of serves as a dig at him (“you created this steady stream of cases, which are a mess”). It’s a wild theory, I admit. But it at least seems more generous than the other obvious explanation — plain old sloppy research.

In the end, I think our Confrontation Clause map is best viewed without Edwards. I just don’t see it as part of the “steady stream” of post-Crawford cases despite Alito’s cite. In my next post, I’ll consider an updated map that makes this edit and also incorporates the names of the justices/opinion authors into the picture. As hinted at by the discussion above, I think that it is unwise to visualize the post-Crawford line without considering the individual positions and strategic alliances of the Court’s justices. Next time I’ll explain more on this point.