Now that Constitution Day is out of the way, I return to my serialized consideration of our recently SSRN-posted article entitled “Beyond the Confederate Narrative.” In the first post of this series, I introduced a map that visually summarized the Article’s essential argument — that contemporary civil-rights jurisprudence remains haunted by a Confederate narrative of state power that survived the Civil War. Today I want to zoom in and consider two maps that look at the Reconstruction period in more detail.

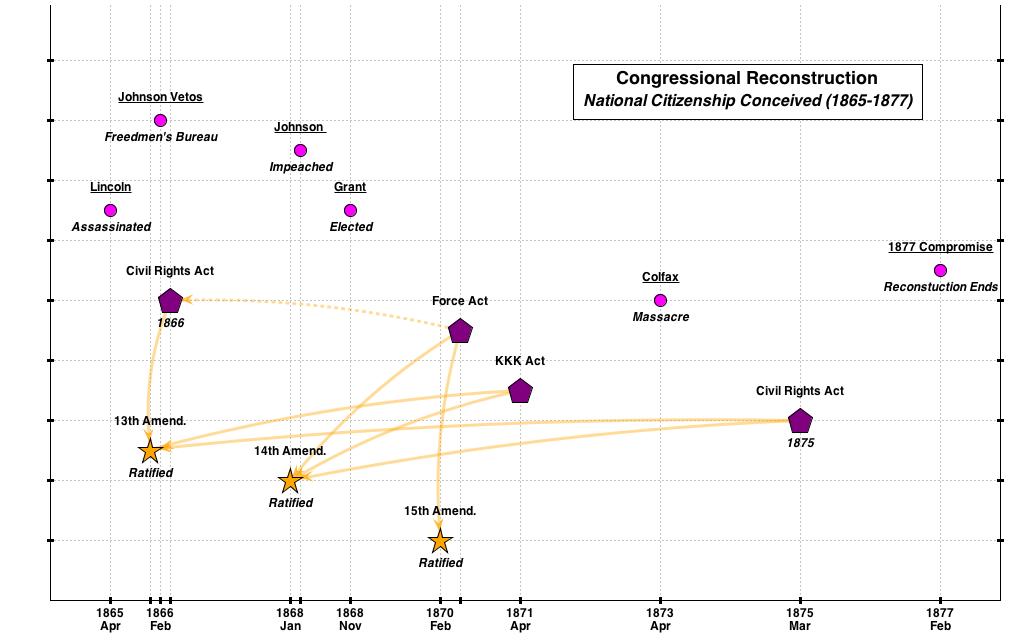

Map 1 above puts Congressional Reconstruction into its historic context. (Click on image to see full-sized map with links to underlying events/legislation). It was a very busy period in terms of legislation: three Amendments and four major Civil Rights Acts were ratified/passed in a single decade. Of course, it was also an extraordinary period period politically with Lincoln’s assassination, Johnson’s impeachment, and then the contested Hayes-Tilden election which led to the 1877 Compromise ending Reconstruction.

A few comments about this particular map are in order. First, this map is to chronological scale — the distance between points on the X axis is proportional. I did this to emphasize the frenzy of activity over such a short period. Second, since there are no Supreme Court cases on this map, the Y-axis on this map has no significance. The Y-axis layout is driven purely by visual considerations. Finally, note that the historic context points represented as pink circles link back to WikiPedia entries. This was a conscious choice — despite its many haters, I actually love WikiPedia. And I love WikiPedia because : (a) it is surprisingly accurate; (b) if not accurate, users have the ability to correct and/or add cites; and (c) I found all the particular entries linked to acceptable.

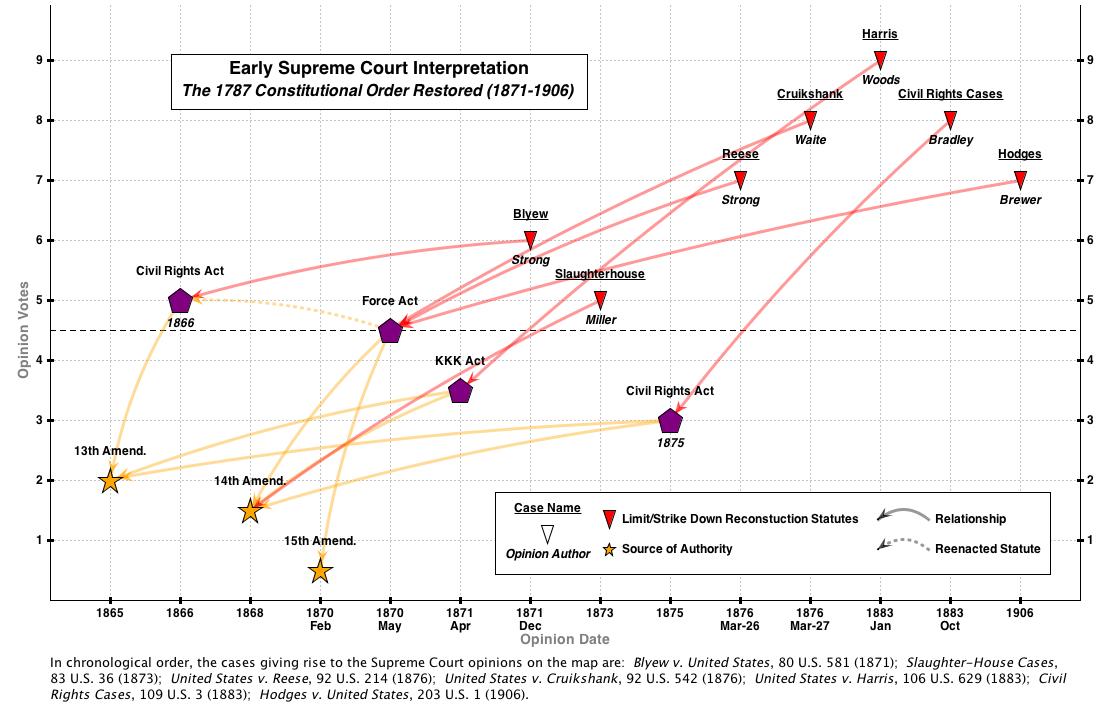

Map 2 visually summarizes our claim that the Supreme Court helped usher in the demise of Reconstruction. It did this by adopting a Confederate narrative of federalism that effectively restored the 1787 constitutional order. We know this claim is controversial, especially in light of recent scholarship by folks like Pamela Brandwein. However, as we state in the article:

Whether one abides by the conventional notion that the Supreme Court was hostile to equal citizenship and human rights for blacks or accedes to the revisionist scholarship of a Court sympathetic to the cause of Reconstruction, the fact remains that the Court’s Reconstruction era jurisprudence did establish three key principles that have had a profound impact on our understanding of the federal government’s role in articulating and protecting the people’s civil rights. First, the Court was reluctant to interpret the Reconstruction Amendments as a reconstruction rather than a narrow reform and restoration of the 1789 constitutional order. Second, the Court appeared unwilling to admit that this restored (rather than reconstructed) constitutional order carved out for the federal government an entirely new role vis-à-vis the states in defining and protecting civil and human rights. And last but not least, even in cases involving horrific anti civil rights terrorism, the Court regularly denied relief to civil rights proponents or granted relief on the basis of technicalities rather than on acknowledgements of federal power.

The cases linked to above — Blyew (1871), Slaughterhouse (1873), Reese (1876), Cruikshank (1876), Harris (1883), the Civil Rights Cases (1883) and Hodges (1906) provide the proof the three propositions asserted.

Whether folks agree or disagree with our readings of the cases, the map provides a novel way to foster discussion. Each Supreme Court case cited is linked to the opinion on Casetext, a fantastic new platform for crowd-sourcing legal research. Cases on Casetext can be linked to commentary and specific sentences or paragraph can be commented upon. It thus provides an extraordinary wiki-like platform to analyze text.

Though Casetext seems primarily targeted at practicing lawyers, I think the platform can also be of great use to scholars studying legal history. To test this theory, I have linked every Supreme Court case on every map in “Beyond the Confederate Narrative” back to Casetext and encourage folks who are interested in these cases to make their own comments and link their own scholarship using the platform. Perhaps it will be possible for us to literally locate our disagreement in interpretations at the level of sentence or paragraph in these profoundly important cases…