As Professor Anna Roberts noted in a popular recent tweet, 1Ls often ask why they read concurrences and dissents. An answer, Prof. Roberts suggested, can be found in this quote from our article “Beyond the Confederate Narrative“:

History has repeatedly shown that brooding in concurrence or dissent can eventually help correct constitutional understandings. Our highest Court has held that states could bar women from the practice of law and that people of African descent were commodities to be bought and sold rather than people in the constitutional sense of “We the People. . . .” It has denied that Jim Crow segregation was a method of subordination and therefore unlawful. It has held that gay and lesbian lovemaking could properly be punished as crime. It has approved the sterilization of persons presumed to be unfit to populate our nation with their progeny and sanctioned the execution of children. The constitutional understandings that led to these results have been challenged and revised. In each case, the challenges were foreshadowed and the revisions modeled by “bubblings-up” in dissents or measured concurrences.

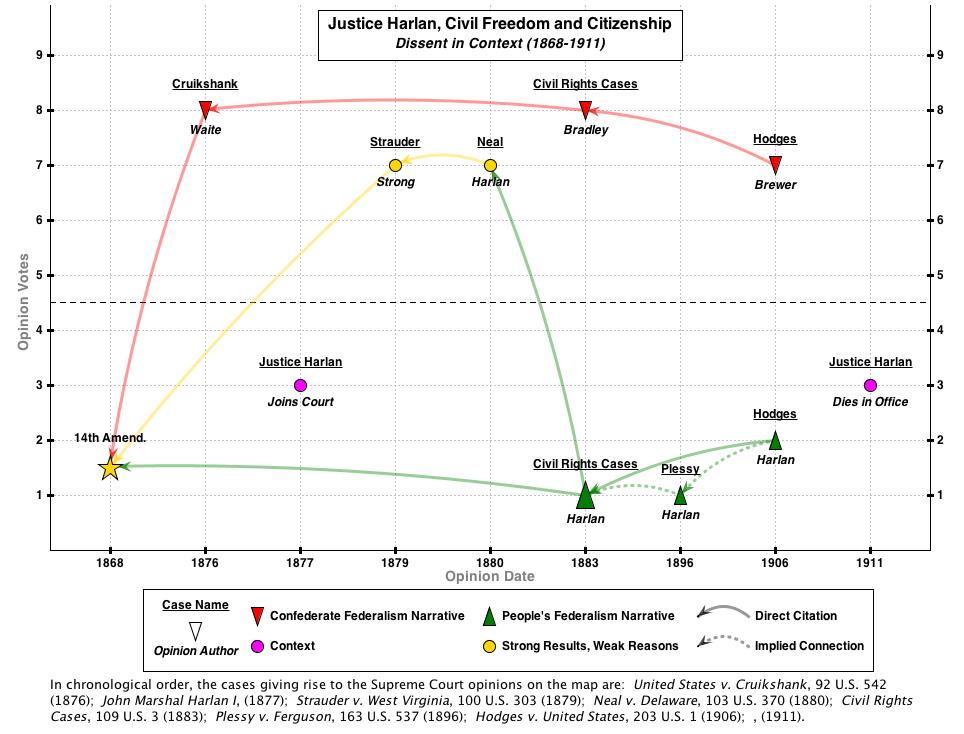

In today’s post about our article (prior posts in this series are here and here), we look at a map of the origins of a vital dissenting tradition that stands in opposition to the Confederate narrative of state power. We call this alternate tradition “the People’s narrative” and hope that its wisdom will eventually prevail just as the wisdom of prior dissents decrying our most infamous constitutional misunderstandings eventually prevailed.

As shown in Map 3 above, the first champion of the People’s narrative tradition was the first Justice John Marshall Harlan. (Click on the image above to get a full-sized image with links to Casetext). Although the Court as a whole reached good results in Strauder (1879) and Neal (1880) by striking down statutes that overtly discriminated against African Americans in jury service, the majority opinions justified their results on very narrow grounds without discussing the deeper meaning of the Reconstruction Amendments. Yet Justice Harlan did expound on that vital deeper meaning when writing in dissent.

Many are already familiar with Harlan’s dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson since it was vindicated 58 year later by Brown v. Board of Education which finally overruled Plessy‘s “separate but equal” doctrine. Unfortunately, Harlan’s dissents in the Civil Rights Cases and Hodges are not nearly as well known. Yet we argue that these dissents are just as important and prescient. They should be read and studied because, in those dissents, Justice Harlan recognized that Reconstruction created a new fundamental right of civil freedom inhering in American citizenship. This understanding, if taken seriously and debated in doctrine, could defeat the ghosts of the Confederate narrative still haunting the Court’s civil rights jurisprudence.

In my next post, I’ll examine how Justice Harlan’s analysis was taken up and extended by some advocates and even some Court justices in during the 1960s civil rights era. Stay tuned!

“infamous constitutional misunderstandings”, oh boy, a little understated, perhaps?