When it comes to same-sex marriage, it’s all about the children. Or so I thought when I first read Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion in Obergefell v. Hodges. Although “safeguard[ing] children and families” technically provided the “third basis” for “protecting the right to marry,” this justification really jumped off the page. Kennedy seemed close to anger when he bluntly concluded: “the marriage laws at issue harm and humiliate the children of same-sex couples.” The affront to children’s dignity was clearly a persuasive argument to Kennedy — as it is to me and so many others.

Imagine my delight then when Catherine Smith came to UB a few weeks ago. Professor Smith was Counsel of Record on the “Scholars of the Constitutional Rights of Children” amicus brief, which Kennedy cited as authority for that key “third basis” about safeguarding children. I loved that argument and wanted to hear her perspective. At her talk, I ended up learning of an area of constitutional law that was entirely new to me: the non-marital children cases.

If you are as ignorant now as I was then, let me give you the basic scoop. From the 1960s until the 1980s, the Court heard a series of Equal Protection challenges to discrimination against the children of non-married parents. Depriving children of property, insurance or other rights based the perceived immorality of having unwed parents has a long history. The non-marital children cases stand as significant victories against this discriminatory tradition. While Professor Smith cited to many different kinds of cases in her brief, non-marital children doctrine played a special rhetorical role.

Since it is not too widely known these days, non-marital children doctrine also affords a great opportunity to experiment with a new feature of the SCOTUS Mapper desktop software. This new feature leverages the Spaeth dataset (a.k.a. Supreme Court Database). For the uninitiated, Spaeth is a massive NSF-funded project that codes every Supreme Court decision from 1946 to the present. Critical variables coded include the issue, legal provision involved, votes, and decision direction. Although some legal scholars view Spaeth skeptically, I find its scheme sufficiently reliable to at least guide an initial inquiry into a new area of doctrine.

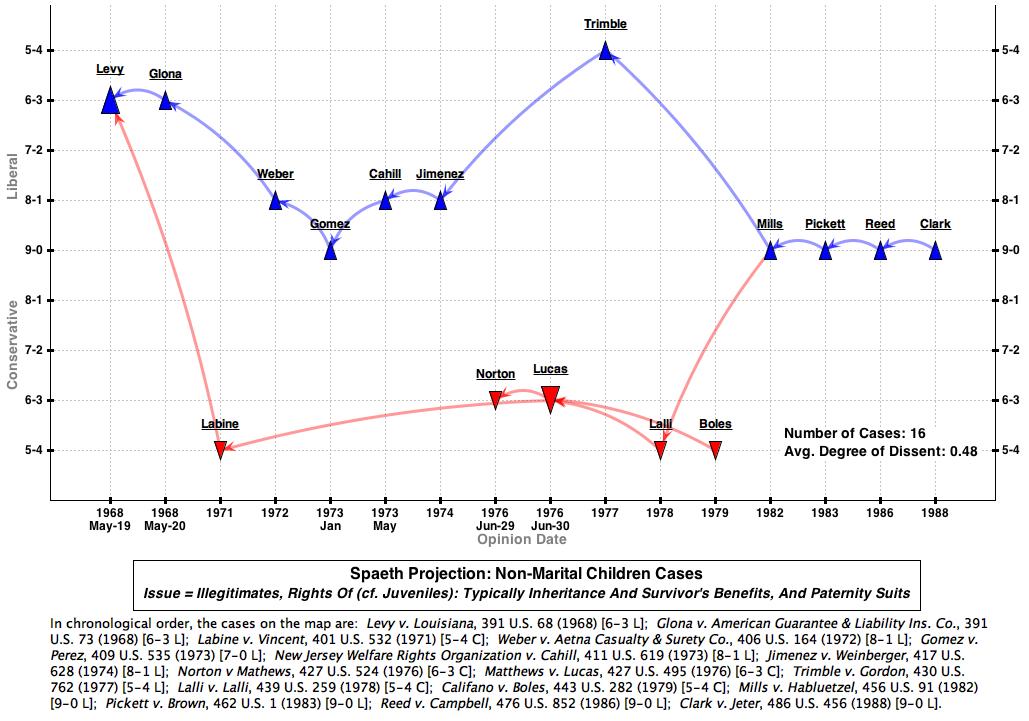

My strategy for mapping started with the Children’s Rights brief. Reading it, I learned that the first case in this line was Levy v. Louisiana (1968) and that the Court’s last pronouncement was in Clark v. Jeter (1988). I looked up both of these cases on Spaeth and found they shared the same codes for issue (“Illegitimates, Rights Of (cf. Juveniles): Typically Inheritance And Survivor’s Benefits, And Paternity Suits”) and for legal provision (“Fourteenth Amendment: equal protection”). Armed with this knowledge, I then searched for all the cases in Spaeth sharing that same issue and legal provision (I also included Fifth Amendment equal protection in my search). This search returned 16 cases.

The map above visualizes those 16 cases. It uses what I call a “Spaeth Projection” to display all the data. The Y axis in this map shows the vote for outcome and decision direction. Liberal-coded decisions occupy the top half of the map and are shown in blue. Conservative-coded decisions occupy the bottom half of the map and are shown in red. Cases displayed towards the middle of the map produced more consensus than those towards the top or bottom.

Readers interested in viewing all the Spaeth data for any case on the map can do so directly. Just click the image to open a full-sized map and then clicking on any case of interest. When examining the underlying data, one point about the Spaeth data bears emphasis. The decision direction codes for the cases — “liberal” versus “conservative” — should not be read politically. Rather, think of this variable as a label for who won or lost a case before the Court. In this particular area, “liberal” cases are those where the claims pressed on behalf of the non-marital child (or children) were successful and “conservative” cases are where the child lost.

According to Spaeth, the children won 11 out of 16 cases. Even more interestingly, we see that children won last four cases in the line 9-0. Without even reading any of the cases, it looks to me that the doctrine started to settle around a “liberal” view towards the middle 1980s. Of course, it would be a mistake to speak too confidently about any area of doctrine without actually reading the cases. I simply put forward this notion of “settling” to demonstrate the kinds of hypotheses Spaeth visualizations can inspire. In addition, my settling hypothesis seems supported by the fact no cases in this particular area appear since 1988.

Over the next few posts, I intend to test my hypothesis against the cases and relevant commentary. I will also build more refined maps of the doctrine. For now, I hope this map provides a useful starting point and big-picture view for any readers interested in pursuing their own studies in this area.