Today the Supreme Court will hear argument in Elonis v. United States, the Facebook “true threats” case. Given the buzz over this case, I’m going to interrupt my current series on the Confrontation Clause in order to briefly consider the doctrinal network at issue in Elonis. Let’s jump right in.

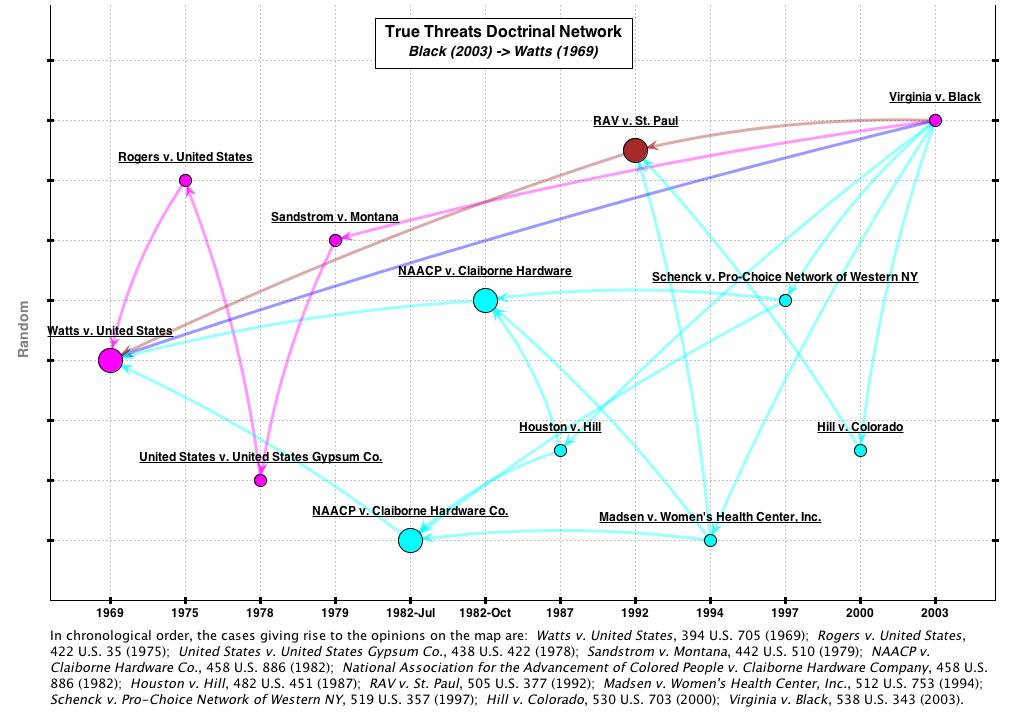

According to the 3rd Circuit opinion under review, the Supreme Court “first articulated the true threats exception to speech protected under the First Amendment in Watts v. United States (1969).” The latest SCOTUS true threats case is Virginia v. Black (2003). The specific doctrinal question in Elonis is whether the true threats exception requires a jury to find the defendant subjectively intended his statements to be intended as threats. The 3rd Circuit concluded that no subjective intent was required. Based on the Black and Watts endpoints, we can easily generate a simple network.

As shown in the map above, Black directly cites Watts (1 degree connection). Black also cites RAV v. St. Paul, which in turn cites Watts (2 degree connection). All the light blue cases form the 3-degree network. The magenta case line is a very specific 4-degree connection to Rogers v. United States. I wanted to include this because the 3rd Circuit in Elonis made reference to Justice Marshall’s concurring opinion in Watts to buttress its view on subjective intent.

Of course, not all the cases in the network above directly concern threats. In order to have a sharper view of the doctrine at issue, I ran the network above through a text filter using Courtlistener’s API. Specifically, I asked the Mapper to display only those cases where the “threats” appeared in opinion text. Here is the result.

Although I have not read the cases in this map, I strongly suspect that the doctrinal analysis/debates contained in these cases will come into play in the Court’s Elonis deliberations. Readers interested in checking out the cases can do so easily by clicking on the images above and then clicking on any opinion — the Courtlistener page will pull right up.

Hopefully, this map demonstrates one application of using network theory to study Court doctrine. It can quickly generate “potential reading lists” for advocates and scholars interested in surveying any given doctrinal area based on given case endpoints. Of course, generating real insights requires reading the texts closely. And that is as it should be.