This is the second installment in a series charting out the Supreme Court’s famous “clear and present danger” line of decisions. In my first post, I proposed a map of this doctrine hyperlinked to the cases analyzed in Sullivan & Feldman, First Amendment (4th Edition). The resulting picture featured two competing lines: the “bad tendency” opinions versus the “imminent incitement” opinions. While the “bad tendency” line dominated the Court’s majority opinions during the early days, the epic “imminent incitement” dissents penned by Holmes and Brandeis eventually won the day. How did this happen? When did the “imminent incitement” school move from dissent to majority? Today I try to tackle these questions by turning to network theory.

As a starting point, let’s return to the Sullivan & Feldman text. The narrative in the text basically jumps from 1951 (when Dennis upheld a “bad tendency”-esque conviction) to 1969 (when Brandenburg announced the modern incitement test). This is a significant gap and all Sullivan & Feldman offer to bridge it is a brief squib to Bond (1966) as well as the observation that “[b]y the 1960s, the Court had become more protective of speech in connection with the civil rights movement, and the fear of domestic communism had abated politically.” In fairness, Sullivan & Feldman no doubt made the right pedagogical call. Their textbook gives students learning modern doctrine all the context they need. Yet we as scholars can still ask: what happened between Dennis and Brandenburg?

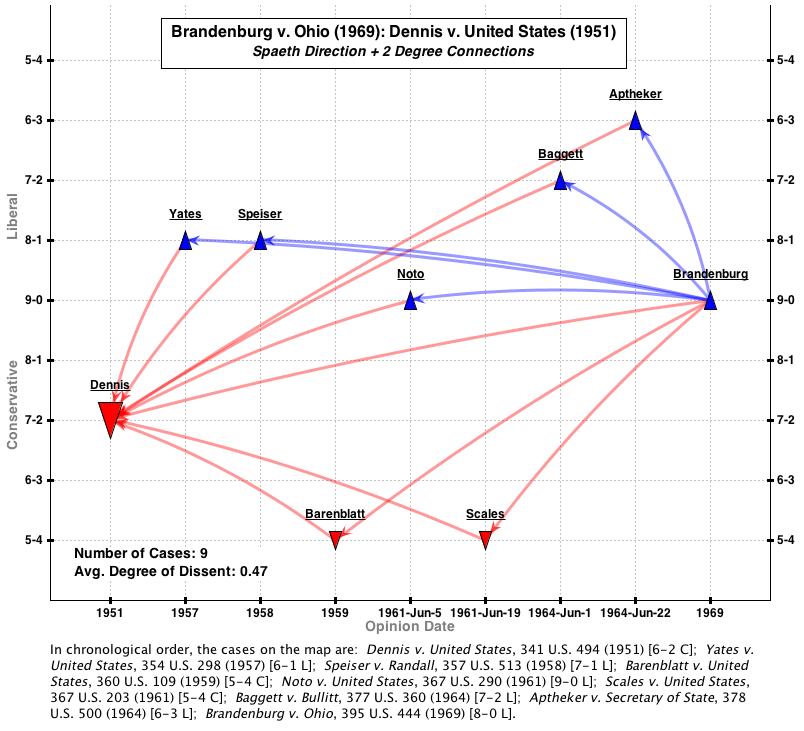

One way to answer this question is to construct a citation network. The map below is an automatically generated 2-degree citation network. This means that the network includes all the cases cited by Brandenburg that in turn cited Dennis.

Note that this is a Spaeth projection. Cases coded by the Supreme Court database as having “conservative” outcomes are red and occupy the lower half of the map; cases coded “liberal” are blue and occupy the upper half. The Y-axis shows the vote for outcome with unanimous judgments occupying the middle. (For a video explanation about Spaeth projections, see here).

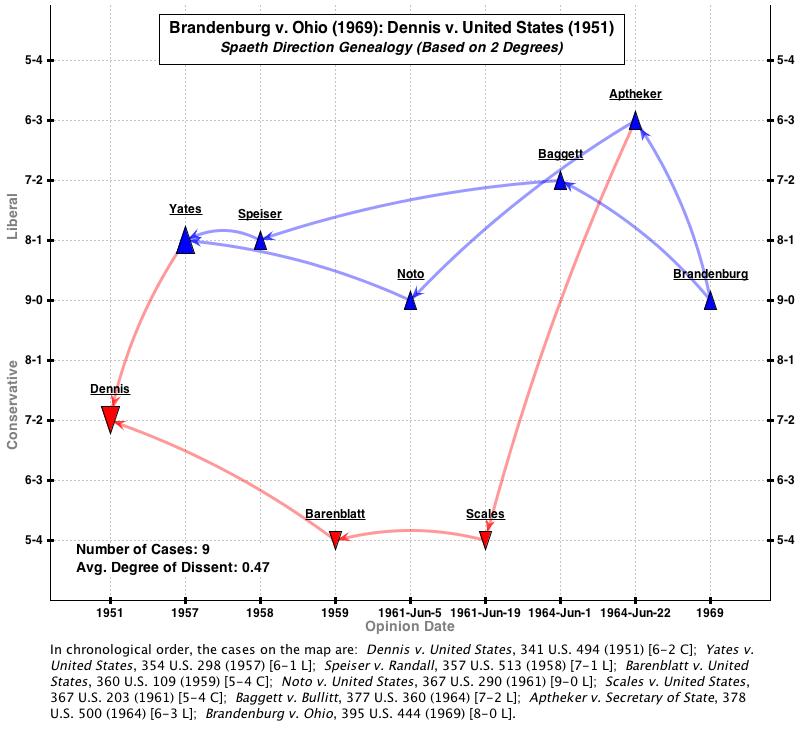

Under the Spaeth rubric, those decisions that uphold free speech rights are “liberal” and those that deny a free speech violation occurred are “conservative.” Looking at this map then, we can see that between Dennis and Brandenburg, the Court handed down 5 liberal/strong-free-speech decisions (Yates, Speiser, Noto, Baggett, and Aptheker) and only 2 conservative/weak-free-speech decisions (Barenblatt and Scales). Using what I call a “genealogy” algorithm, we can then display the citations between cases in the network to highlight the competing lines.

The map above shows cases going both ways after Dennis, but hints at some tension from 1959 through 1964. During this period you have two 5-4 conservative decisions (Barenblatt and Scales) followed by a 7-2 liberal (Bagett) and then a 6-3 liberal (Apthekar). We need to look closer. One way to do this would be to read the opinions. (Readers interested in this approach can click on the map and cases therein to access opinions directly). Another way is to dive deeper into the network. Let’s try that approach.

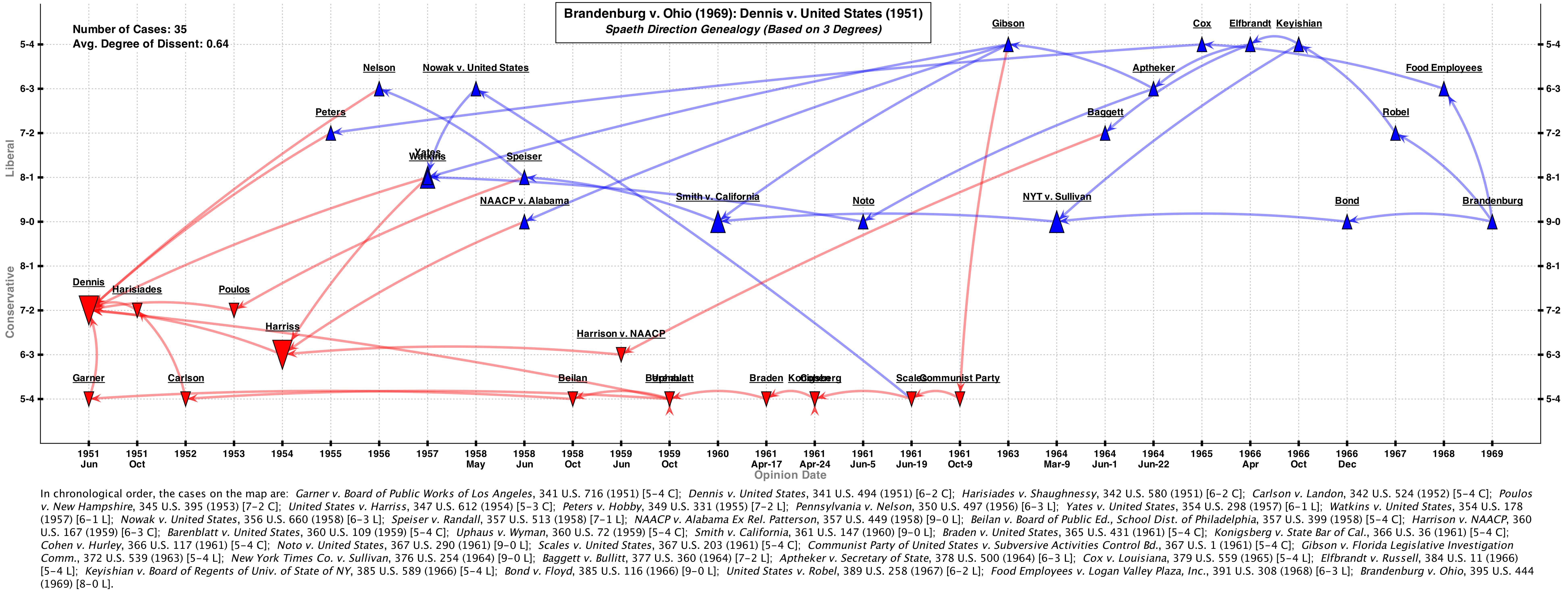

This third map is the 3-degree citation network connecting Brandenburg to Dennis. (To open a full-sized map in a separate window, click on the image). This network therefore includes all the 2-degree cases as well as 3-degree cases (i.e., cases cited by 2-degree cases that in turn cite Dennis). I also ran this network through the genealogy algorithm, which cleans up the network considerably.

One pattern emerges particularly sharply from this map. At the bottom, we see a whole series of linked 5-4 conservative decisions extending from 1951 (Garner v. Board of Public Works of Los Angeles) all the way to 1961 (Communist Party v. Subversive Activities Control Board). Yet after 10 decisions, this line abruptly stops. In 1963, we suddenly see a 5-4 liberal decision that cites Communist Party — Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigation Commission. The tide has turned. After Gibson, the network consists of exclusively liberal decisions all the way to Brandenburg. This pattern strongly suggests that something — or some things — happened between the Court’s decisions in Communist Party (1961) and Gibson (1963).

The network approach thus helps us shape an inquiry and sharpen our focus. We are able to identify many potentially relevant cases — 33 in the 3-degree network between Dennis and Brandenburg — and then narrow our gaze to a smaller subset based on an observed shift. This seems useful to me. Of course, work remains to be done. Creating the network does not end the inquiry so much as move it along.

In my next post, I will focus in on the key period between 1961 and 1963 identified through this network analysis. Until then, stay tuned!

** Note to First Amendment Researchers ** If you wish to read or examine the opinions in the 3-degree map above, you’ll have to use this link. Due to current technical limitations, this map is a little on the small side. However, when used in conjunction with this full-sized image, you should be able to figure out all you need to get the right links.