This week I’ve been mapping out the Supreme Court’s “clear and present danger” doctrine. Post #1 visualized the 50 years from Schenck (1919) to Brandenburg (1969) according to the narrative in Sullivan & Feldman’s leading Con Law textbook. Post #2 examined an apparent gap in that narrative between Dennis (1951) and Brandenburg. Based on a citation network analysis, I hypothesized that the key shift from weak to strong free-speech protection occurred between Communist Party of USA v. Subversive Activities Control Board (1961) and Gibson v. Florida Investigative Commission (1963). Today I wrap up this series with a new map that illustrates the thesis that the Court’s modern era of liberal incitement jurisprudence began with Justice Frankfurter’s departure and replacement by Justice Goldberg.

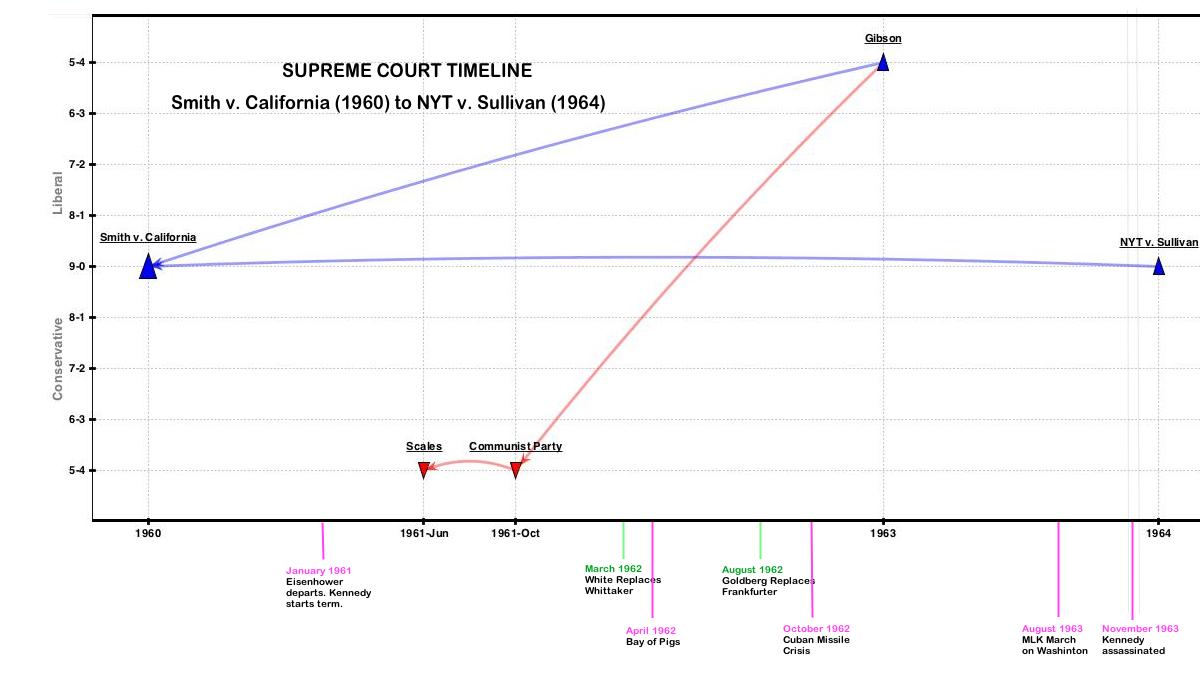

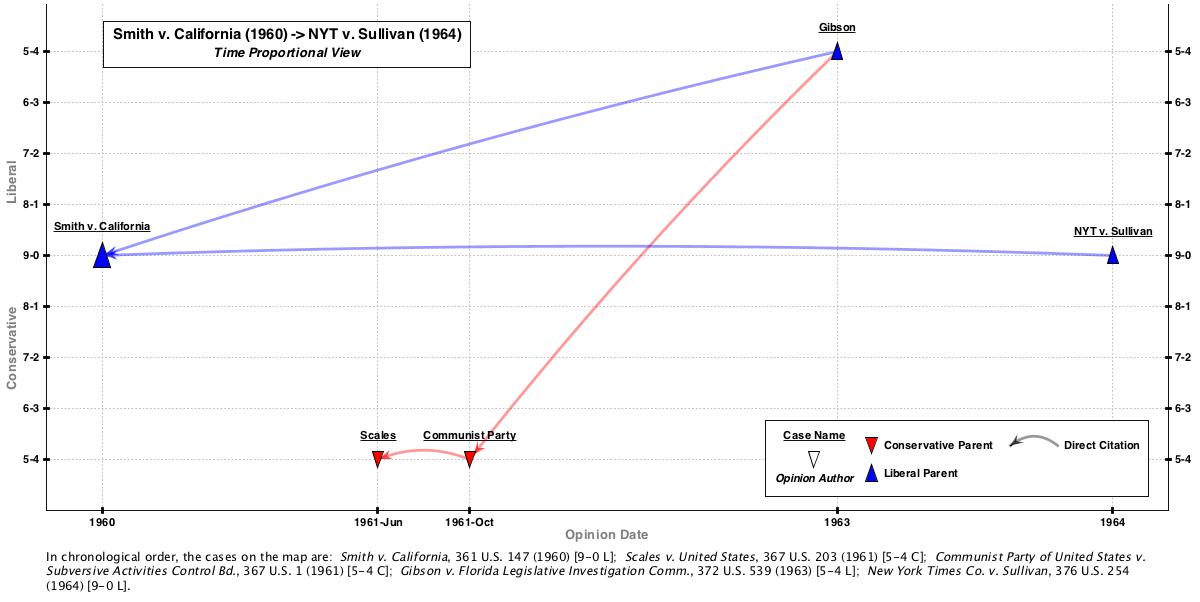

To set the stage, let’s zoom in on the period in question. Here is a snippet of the Dennis to Brandenburg network from 1960 to 1964.

Note first how the opinions above are proportionally spaced along the X-axis. Unlike the usual evenly-spaced-opinion schematic, this is a genuine timeline view.

The key part of the map is the movement along the line from Scales (1961) to Communist Party (1961) to Gibson (1963). (Smith, the earliest case on the map concerns obscenity not incitement/subversion. I include it simply to help define chronological boundaries.) Oversimplifying just a bit, Scales and Communist Party were both 5-4 decisions where the majority effectively acquiesced to McCarthyism. The majority and dissenting lineups were the same in both cases: [Majority] Frankfurter, Clark, Harlan, Whittaker; [Dissent] Black, Douglas, Warren, Brennan. Notably, Frankfurter wrote the majority opinion in Communist Party. [To see lineups on Oyez, click here for Scales and here for Communist Party].

Then came turnover at the Court. In March 1962, Justice Whittaker was replaced by Justice White. As we’ll see, this change did not turn out to be significant. In August 1962, Justice Frankfurter was replaced by Justice Goldberg. Then the Court handed down Gibson, which effectively pushed back on anti-communist investigations by a state subversive-activities type board. Not coincidentally, Justice Goldberg wrote the Gibson opinion. The new “strong free speech” majority consisted of Warren, Brennan, Goldberg, Black and Douglas. The dissenters were Clark, Harlan, Stewart, and White. Thus we see that White followed the same “weak free speech” line that Whittaker did in Communist Party. [Gibson lineup via Spaeth here].

We can visualize the sequence just described using a timeline map. Click on it to open a full-sized image in a separate window.

The green lines at the bottom of the map indicate when Whittaker and Frankfurter left the Court. To amplify the timeline concept, I also added magenta lines to display important political events of the time.

The green lines at the bottom of the map indicate when Whittaker and Frankfurter left the Court. To amplify the timeline concept, I also added magenta lines to display important political events of the time.

The map reminds us how intense this period was. Eisenhower left office in 1961 with his famous “military-industrial complex” speech. The Court handed down Scales and Communist Party after President Kennedy took the reins. Then you see the replacement of Whittaker and Frankfurter interspaced with the Bay of Pigs and Cuban Missile crises. After Gibson, you have the March on Washington and Kennedy’s assassination. The times they were a changing!

It probably comes as no surprise to First Amendment scholars that Frankfurter’s departure was a key development in this doctrine. After all, he wrote the majority opinion in Gobitis (1940) which upheld the compulsory saying of the Pledge of Allegiance. Frankfurter then dissented in Barnette (1943), which reversed Gobitis and now stands as another classic statement of modern First Amendment values. Frankfurter was a patriot and a tireless advocate of judicial deference. This served him well often, but not so much on First Amendment questions. At least that is how I see it.

Even if my substantive First Amendment analysis misses the mark, I hope there is some use to the Timeline form explored above. I think visualizing the Court’s relationship to events of the day — placing its doctrinal decisions in political context — is a fruitful endeavor. As always, I’d love to hear what others think. What other visualizations have you seen that put Court doctrine in political context?

Amazing conceptual work, Colin!

Thanks Dennis!

Yes! The timeline approach is wonderfully promising. Can’t wait to use it. The interpretive possibilities are endless. Also, it’s nice to see Goldberg getting his due. Very important across the board in civil rights, I think.