Like many others, I cheered when South Carolina finally lowered the Confederate Flag from its capitol grounds last July. Though activists had been calling for the flag’s removal for most of the 54 years that it flew, their call was not finally acted upon until after the terrible June 17 massacre at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Now that the flag no longer flies, we might ask: “Has Confederate ideology finally been defeated?”

In a paper entitled “Beyond the Confederate Narrative”, Peggy Cooper Davis, Aderson Francois and I answer that question with a loud “No!”. We argue that a Confederate narrative continues to haunt the Supreme Court’s civil rights jurisprudence. This narrative has its origins as a state-power justification for the right to engage in human chattel slavery. In our article, we show how the Confederate narrative about federalism survived the Civil War and Reconstruction and then protected Jim Crow and other forms of human subordination. Although beaten back during the civil rights movements of 1960s, the Confederate narrative survived in doctrine and has reemerged to help defeat claims that certain fundamental human rights are federally guaranteed and federally enforceable.

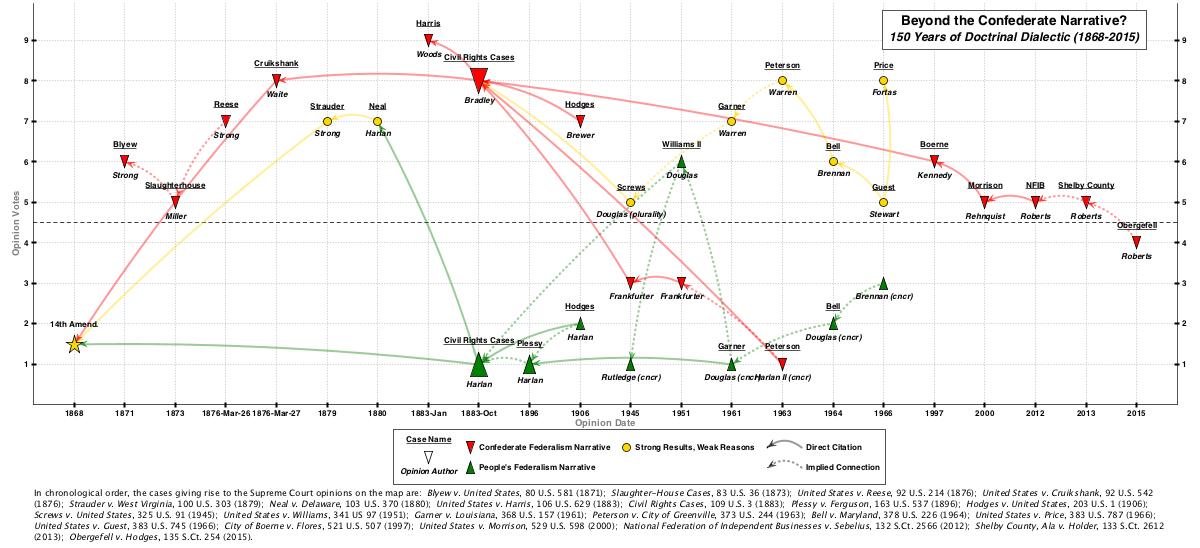

Since our argument proceeds from a thorough reading of Supreme Court cases and relevant historical documents and commentary, it is admittedly long and heavily footnoted. However, the basic arc of the argument is summarized in a serious of interactive doctrinal maps. (For the uninitiated, instructions on how to read these maps are here.) Over the next couple of posts, I’ll examine these maps.

To start, consider this top-level map that shows the basic sweep of the entire argument. (As usual, click to open the full-sized image a separate window).

Although the map covers the entire period from the end of the Civil War until 2015, the focus is really on three discrete sub-periods of Court doctrine: (1) Reconstruction cases from Blyew (1871) to Hodges (1906); (2) civil-rights era-cases from Screws (1945) to Price and Guest (decided on the same day in 1966); and (3) modern cases from Boerne (1997) to Obergefell (2015). Within these sub-periods, the focus in on cases that dealt with the balance of state versus federal power to enforce civil rights.

The cases embracing the Confederate narrative, as we see it, are shown in red. The map thus suggests that modern cases like the majority decisions in Shelby County (2013) and Morrison (2000) are linked ideologically and doctrinally to Reconstruction-eviscerating cases like Cruikshank (1876) and the Civil Rights Cases (1883). Some may find this claim of genealogical connection outrageous; others will see it as obvious. Either way, I’ll eloborate on the basis for our claim in forthcoming posts by looking at the three periods outlined above in more detail. Stay tuned!