As legendary civil rights activist Bob Moses often reports, the sit-in demonstrators, freedom riders and voting rights activists of the 1950s and 60s enacted a freedom that they understood to be their birthright. Speaking in the voice of a Movement activist, Moses teaches that “We, as People of the United States claimed with our bodies the rights to occupy public space as civic equals and to be counted in the political process.”

This performance of citizenship brought Movement activists into conflict with both state and private actors who refused to recognize the equality of African Americans. Such conflicts often resulted in legal actions that pulled the Supreme Court into the heated national debate over civil rights and raised key questions about the appropriate reach of federal power. In our article “Beyond the Confederate Narrative” we analyze two kinds of claims that the Movement called upon the Supreme Court to adjudicate two kinds of claims- “enforcement” and “enactment”. (For visual summary of our analysis about how this civil rights debate played out post-Reconstruction, see part 1, part 2, and part 3 of this blog series).

In “enforcement” cases, the Federal government attempted to prosecute individuals for acts of domestic terrorism against civil rights advocates. The Court considered challenges to these federal prosecutions based on the ground that the national government had improperly usurped the States’ police power to prosecute private violence. On the other hand the “enactment” cases concerned prosecutions against Movement activists who broke state laws or customs by inhabiting public spaces on an integrated basis or attempting to diversify local political processes. In these cases, the Court heard challenges to prosecutions on the ground that activists could not be punished for exercising their national constitutional rights.

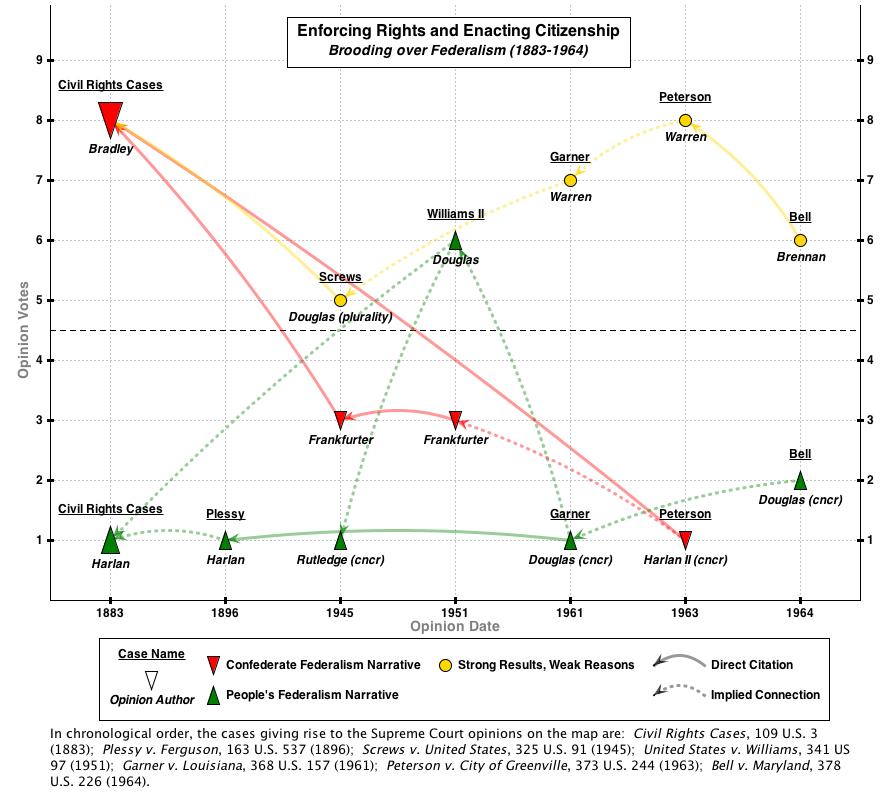

Cases in both the enforcement and enactment category tested the boundaries of the national government’s power to define and protect its People’s rights. Each case was a contest of state and federal power, with states claiming supremacy in the realm of policing human behavior and the national government claiming supremacy as a guardian of human rights. We present two maps that illustrate the most important cases that in this line.

In the map above, the enforcement cases are Screws (1945) and Williams (1951). Although neither of these cases actually concerned violence against civil rights activists, they both involved federal prosecutions against state law enforcement officers for violations of civil rights. Local cops had acted brutally and violently and local authorities had refused to prosecute their actions as crimes. In the Court, justices debated the limits of state versus federal power in a manner that perfectly captures the dialectic between Confederate and People’s narratives. The debate in Screws and Williams subsequently framed how the conversation turned when true Movement cases finally arrived at the Court.

Three key enactment cases — Garner (1961), Peterson (1962), and Bell (1963) — are also shown in this map. All three cases invalidated convictions of protestors trying to integrate state facilities. Although the result was pro-civil rights in each case, it was in the dissenting or concurring opinions of Justice Douglas in particular that announced the most progressive vision of federal power’s right to confront state apartheid. (Readers interested in the fascinating details of the cases can click on the map above to link directly to the underlying opinions via Casetext.)

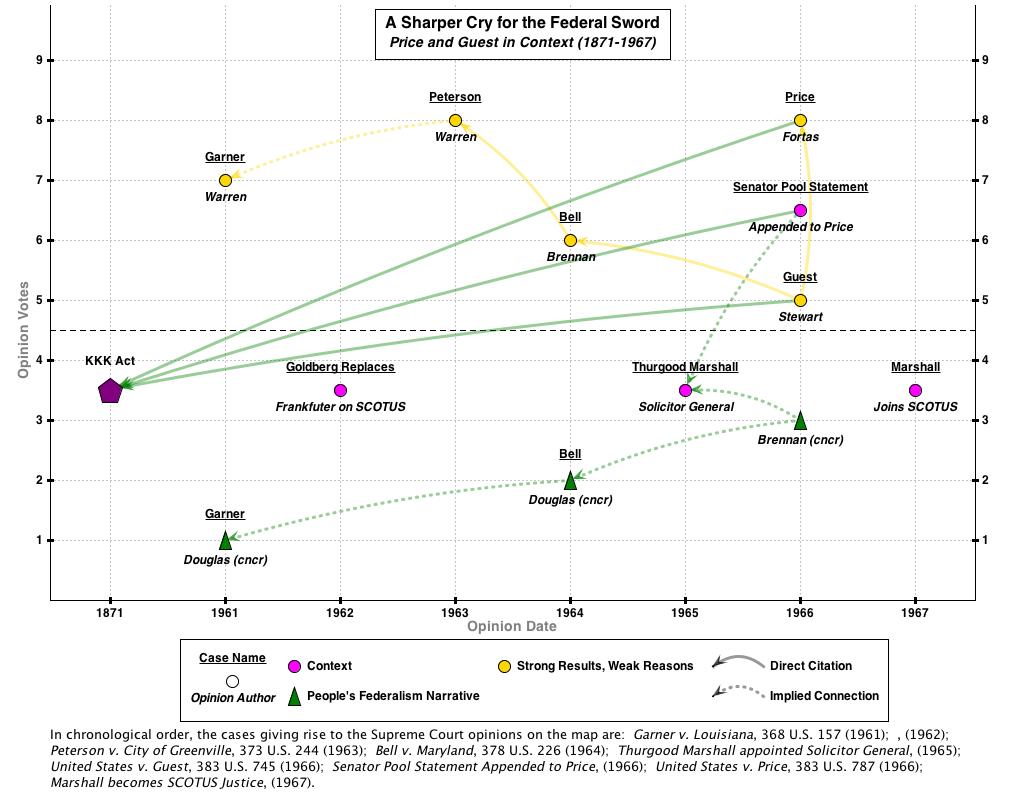

This second map focuses attention on two critical and too-often overlooked enforcement cases — Price and Guest. Decided on the same day in 1966, Price concerned federal prosecutions of those accused for the murders of James Cheney, Robert Goodman and Michael Schwerner while Guest concerned prosecutions against the accused murderers of Lemuel Penn, an African American army reservist. The map highlights vital role that then-Solicitor General Thurgood Marshall played in introducing key Reconstruction legislative history into federalism doctrine — Senator Robert Pool’s statement regarding the 1871 KKK Act. Of course, it was the language from this Act that provided the basis for federal prosecutions.

This map thus demonstrates the importance of the non-Confederate understanding of Reconstruction to justify federal prosecutions of private actors for civil rights violations. Thurgood Marshall grasped this understanding from his pioneering civil rights work and his careful study of history. Though our article, we seek to recollect and reclaim the tradition Marshall embraced then. Our maps chart the lineage and progression of this tradition in Court doctrine. Next time, I will finish up this blog series by examining with one final map. This last map will turn from history to more contemporary Court doctrine in order to advance the argument that the Confederate narrative still haunts our civil rights jurisprudence.