Yesterday the Supreme Court handed down its first opinion of the 2015 Term, Maryland v. Kulbicki. In a per curiam opinion, the Court reversed a Maryland Court of Appeals decision that had ordered post-conviction relief for Kulbicki based on his counsel’s ineffective failure to challenge flawed Composite Bullet Lead Analysis (CBLA) testimony. Over at the Forensics Forum, Professor Brandon Garrett offers good analysis on why the Court’s decision is flawed and unnecessarily stingy, especially when compared to last Term’s per curiam decision in Hinton v. Alabama. To facilitate further discussion, I offer two maps that provide Kulbicki‘s doctrinal context.

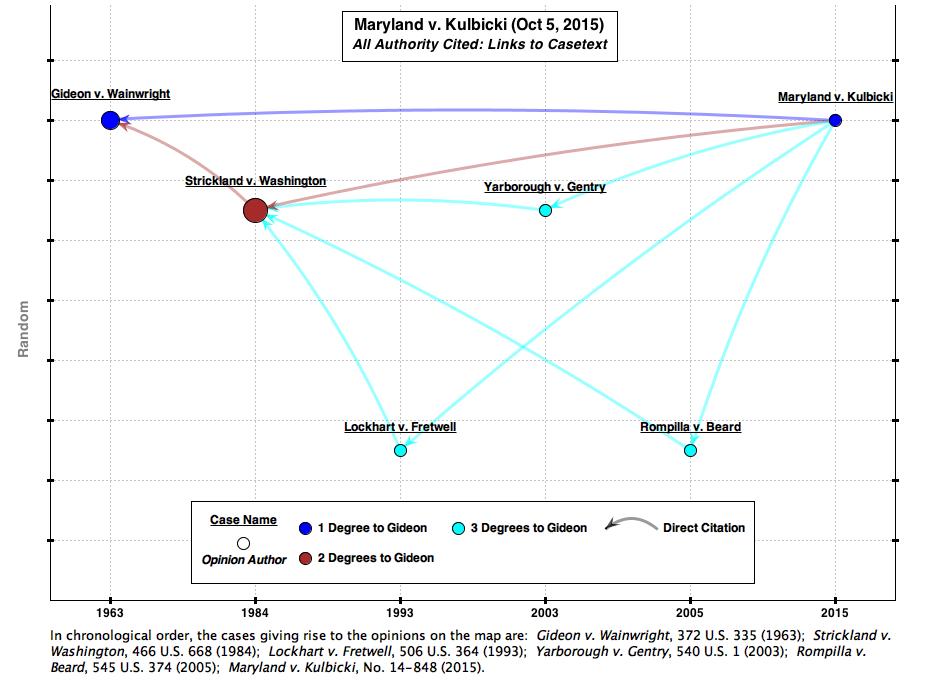

As this first map shows, Kulbicki only cites five other Supreme Court opinions to justify its analysis. Citation analysis shows the cases form a tight family network. Consider that the earliest case Kulbicki cites is 1963’s Gideon v. Wainwright, the seminal right-to-counsel case. The next earliest case invoked is Strickland v. Washington, which lay the foundation for modern Ineffective Assistance of Counsel (IAC) doctrine. Strickland itself cites Gideon. Finally, Kulbicki cites three more recent IAC cases, all of which cite Strickland, which cites Gideon. Thus, Kulbicki connects every case in its network to Gideon at a maximum of three degrees.

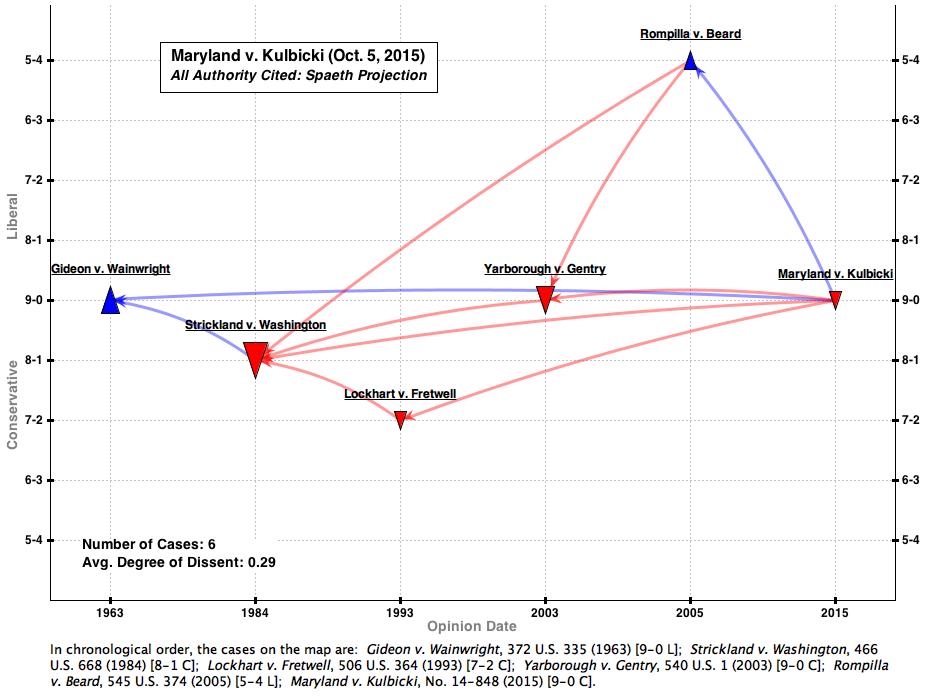

Another way to visualize Kulbicki‘s network is pictured above. It uses a Spaeth Projection that shows both votes for outcome for cases and whether the cases “liberal” or “conservative” according to Spaeth. Interestingly, the average “degree of dissent” in this network is very low (0.29). For reference, a 9-0 case is said to have a 0 degree of dissent; a 8-1, a 0.25, a 7-2, a 0.5, a 6-3, 0.75, and a 5-4 a 1.0. Thus, this map shows the opinion largely cited uncontroversial authority in support of what the Court presumably hoped would be an uncontroversial conclusion.

Of course, the Kulbicki court does cite one 5-4 decision, 2005’s Rompilla v. Beard. Yet this too is a savvy rhetorical choice. In granting IAC relief, the Rompilla majority observed that failure to look at a file the prosecution says it will use is ineffective, unlike “looking for a needle in a haystack, when a lawyer truly has reason to doubt there is any needle there.” In Kulbicki, the Court denies IAC relief and cites Rompilla for the affirmative proposition that lawyers don’t have to look for needles. The message is: even in a close-call case not too long ago, the liberal majority agreed that lawyers don’t have to look for needles; that’s how today’s unanimous Court sees this case. One need not agree with the outcome in Kulbicki to appreciate its doctrinal rhetoric.

very complex explanation. thanks for the information

Kulbicki connects every case in its network to Gideon at a maximum of three degrees. this is fact by the way

tq, good article

thanks for information

Good article. Thanks for your article

Thanks for sharing