Last week, the Supreme Court heard argument in Montgomery v. Louisiana. Two issues were on the table. The first is whether the Court’s 2012 Miller v. Alabama decision — striking down mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juveniles to under the Eighth Amendment — applies retroactively to cases on collateral review. The second issue is whether the Court even has jurisdiction to hear Montgomery’s appeal. According to reports about the argument, the Justices seemed far more interested in, and confounded by, the second issue.

This is unfortunate. Relief for Mr. Montgomery (and those similarly situated) is only possible if the Court actually reaches the retroactivity question. And perhaps Mr. Montgomery deserves relief. Though he committed a terrible murder, he was only 17 years old when he did it. Though he killed a law enforcement officer, he did so way back in 1963 during a turbulent and tension-filled time. And Mr. Montgomery has been in prison ever since. That’s 52 years and counting. To me at least, that smells like cruel and unusual punishment.

So let’s imagine for a second that the Court does reach the retroactivity issue. On the surface, prospects here do not look good. According to the governing precedent of Teague v. Lane, new constitutional rules announced in criminal cases ordinarily do not apply retroactively to cases on collateral review. Teague envisioned two exceptions to this general rule. First, retroactivity is possible for “substantive” decisions — those changing the definition of what is criminal or or what punishment can be imposed. Second, retroactivity is also possible for new “procedural” decisions if those decisions announce “watershed rules” that re-conceptualize what constitutes basic fairness in a criminal trial.

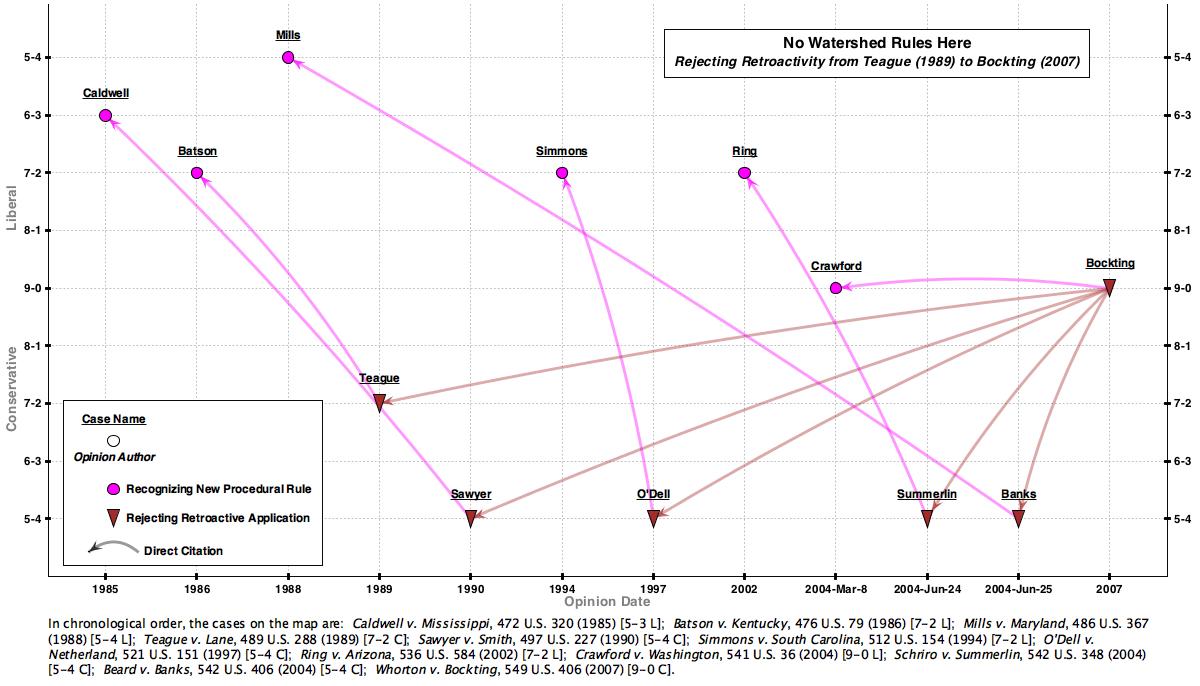

Although Mr. Montgomery and the parties supporting him argue that Miller laid down a new substantive rule thus invoking Teague‘s first exception, I want to focus on the second exception. For the “watershed rule of criminal procedure” exception demonstrates just how illusory justice can be for those trapped in our system of mass incarceration. The fact is that the Court has never recognized a watershed rule under Teague. As my colleague Garrett Epps quipped the other day: “Watershed rules are like Bigfoot; everybody’s heard of them, but nobody’s seen one.” Consider the following map.

(Click on the image to open a full-sized version of the map with links to the underlying opinions. To open the identical map with links to Supreme Court Database entries for each case, click here.)

The magenta circles on the map represent decisions where the Court announced important new procedural rules — Caldwell, Batson, Mills, Simmons, Ring and Crawford. Even though these decisions significantly changed the law and often concerned life-and-death issues, the brown triangles represent the Court’s universal subsequent rejection of retroactive application for the rules. No matter the rule, the Court decided that Justice did not require looking back.

Two cartographic points deserve mention. First, Summerlin and Banks were decided on the same day. The map only changes Banks‘ decision date for readability’s sake. Second, the map makes apparent that retroactivity very much divides the Court. As shown by the Y-axis (using a Spaeth projection), four of the decisions rejecting retroactivity — Sawyer, O’Dell, Summerlin, and Banks — involved 5-4 splits. Interestingly, Spaeth classifies all the decisions announcing new rules as “liberal” and all the decisions rejecting their application was “conservative.”

Is it possible that one day a watershed rule will emerge from this doctrinal desert? Perhaps. As mentioned above, it is not likely that Montgomery will be this case since jurisdiction stands in the way and the parties are angling relief under Teague‘s substantive exception. But advocates and scholars should not despair of ever finding a watershed rule. The persistence of 5-4 splits on retroactivity shows kinks in the Court’s armor. With the problem of mass incarceration now getting mainstream attention, the Court may realize that retroactive application of important new rules is one easy way to get very old men and women out of prison. And the time for that innovation is well past due.