In its second opinion of the 2015 Term, Mullenix v. Luna, the Court held a police officer immune from liability for his role in killing a fleeing suspect. This is how Justice Sotomayor’s solo dissent describes the conduct ultimately protected by the Court:

Chadrin Mullenix fired six rounds in the dark at a car traveling 85 miles per hour. He did so without any training in that tactic, against the wait order of his superior officer, and less than a second before the car hit spike strips deployed to stop it. Mullenix’s rogue conduct killed the driver, Israel Leija, Jr.

Per Sotomayor, clearly established Fourth Amendment doctrine dictates that “an officer in Mullenix’s position should not have fired the shots.” So, she concludes, immunizing the officer’s use of deadly force was dead wrong.

Although Sotomayor’s argument is powerfully stated, it suffers from a fatal flaw. This fatal flaw is perfectly stated in the per curiam opinion:

The Court has [] never found the use of deadly force in connection with a dangerous car chase to violate the Fourth Amendment, let alone to be a basis for denying qualified immunity… The dissent can cite no case from this Court denying qualified immunity because officers entitled to terminate a high-speed chase selected one dangerous alternative over another.

Alas, these words do not lie. The Court’s car chase cases have uniformly sanctioned the use of deadly force. Sotomayor’s dissent fails to adequately deal with this doctrinal reality.

Of course, just because it is reality doesn’t mean that the Court’s current deadly force doctrine is well reasoned or just. Indeed, Sotomayor’s dissent fairly characterizes the Court’s opinion as blessing of a ” ‘shoot first, think later’ approach to policing.” While Sotomayor’s dissent appears in tune in with the times, the per curiam opinion seems utterly tone deaf to today’s maelstrom over police violence. At the same time, doctrinal reality is doctrinal reality.

So the real question becomes: can this reality change?

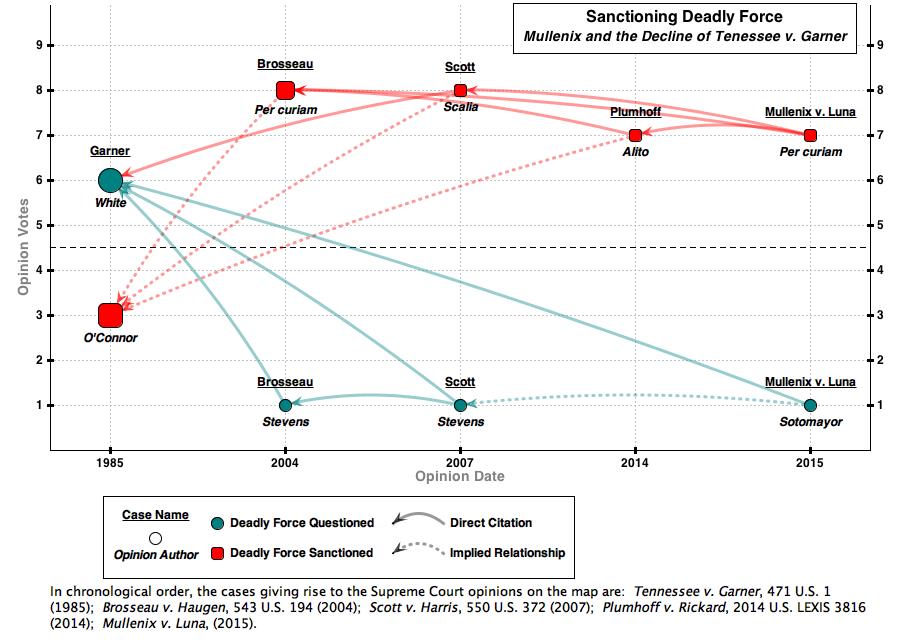

To answer this question, a quick review of relevant Fourth Amendment history is in order. Consider the following doctrinal map:

(Click on image to open full-sized version with links to underlying opinions).

As the map shows, deadly force doctrine was not always so bleak. The seminal early case is Tennessee v. Garner, which invalidated a law authorizing police deadly force exercised when apprehending even non-dangerous fleeing suspects. In a 6-3 opinion written by Justice White, the Court held that the Fourth Amendment prohibited such lethal force to effect a seizure unless the police had “probable cause to believe that the suspect poses a significant threat of death or serious physical injury to the officer or others.”

Critically, Garner‘s doctrinal formulation was contested from the outset. Justice O’Connor, joined by Chief Justice Burger and then-Justice Rehnquist, dissented. As the map shows, the views expressed in O’Connor’s dissent effectively came to rule the roost over time.

Close to twenty years after Garner, the Court decided Brosseau v. Haugen. In that case, the Court granted immunity to a police officer who shot a suspect in the back as he attempted to drive away from a parking lot. Although the opinion was per curiam, it is clear that two of the Garner dissenters — O’Connor and then-Chief Justice Rehnquist — were part of the coalition. Justice Stevens, the sole remaining member of the Garner majority then sitting on the Court, dissented. He saw the writing on the wall. After Brosseau, came Scott v. Harris. This time the Court found that the Fourth Amendment was not violated by police use of a “push bumper” maneuver to apprehend a speeder; the unarmed speeder was left paralyzed by the subsequent crash. Stevens again was the sole dissenter.

The last case before Mullenix is Plumhoff v. Rickcard. In that case, the Court exonerated a police officer’s killing of a suspect in a parking lot on both Fourth Amendment and Qualified Immunity grounds. By now, Stevens had left the Court and nobody dissented from the majority’s decision. (Justices Breyer and Ginsburg did not join every part of the opinion but did not write separately; Sotomayor was silent). Although the facts of Plumhoff were admittedly grim — the suspect nearly hit a number of cops with his car — it still seems a missed opportunity for Sotomayor. She could have done more to protest the erosion of Garner, which would have better set up her otherwise compelling dissent in Mullenix.

One lesson to be drawn from this narrative is that dissents can shape doctrine over the long run. O’Connor’s dissent in Garner evidently presaged the Brosseau per curiam opinion. Cheers to Stevens for flying the true Garner flag in his Brosseau and Scott dissents and boos to his colleagues — especially Breyer and Ginsburg! — for failing to join him. Yet Stevens’ prescient analysis need not be forgotten. His dissents offer a potent alternate interpretation of Garner more in keeping with that seminal case’s original vision. Praising Sotomayor’s Mullenix dissent is all good, but we can help the dissent survive and thrive by making explicit its connection to an older and deeper doctrinal struggle.