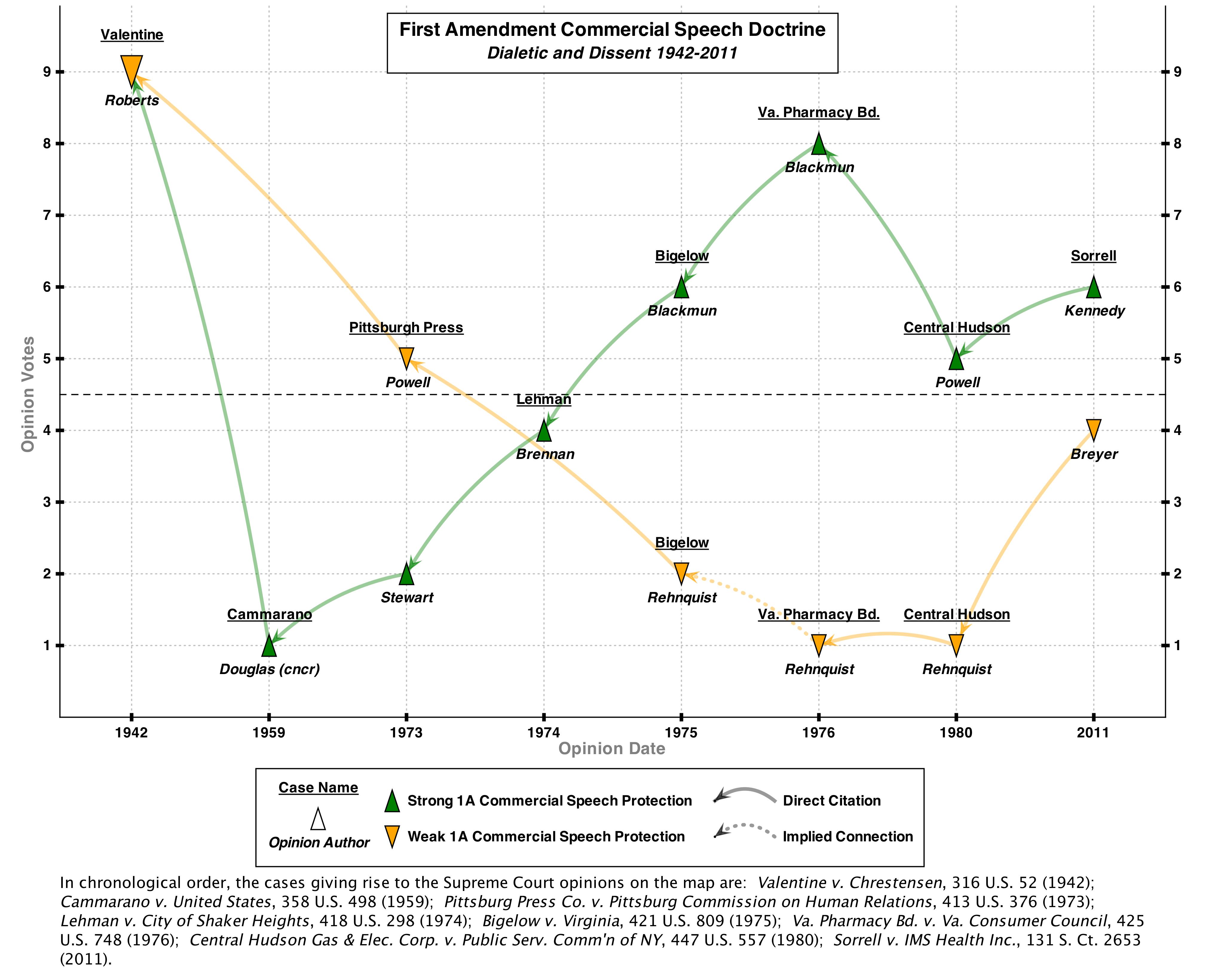

Earlier this week, I looked at the challenges of editing a Supreme Court citation network through the lens of the First Amendment line of cases pertaining to commercial speech. Today I want to fill in the doctrinal picture just a little and highlight a different kind of doctrinal map. Specifically, I use a standard vote-based map to illustrate how the doctrine-altering Virginia Pharmacy Board (1976) majority decision emerged from prior dissents.

By way of background, know that purely commercial speech (i.e. advertising) lacked explicit First Amendment protection until the Court’s Virginia Pharmacy Board decision. Prior to that, the non-protected status of commercial speech has been affirmed in a line of cases stretching back to a unanimous 1943 case called Valentine v. Chrestensen. So how did the doctrine change? Here’s a visual explanation:

The map above uses a “standard” display where the Y axis shows the number of votes a particular opinion receives. Unlike the Spaeth visualizations in my last post, this standard display makes room for dissents and concurrences and names the authors of opinions. As a result, the standard display better reveals the dialectics in Supreme Court doctrine.

The map illustrates that the Court’s formal decision to grant commercial speech First Amendment protection in Virginia Pharmacy Board was presaged by a series of dissents and concurrences. Justice Douglas, a member of the original unanimous majority in Valentine expressed doubt about that case’s viability in a 1959 concurrence (Cammarano). The turning-point case was Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Pittsburgh Commission on Human Relations (1973). The unprotected nature of commercial speech led to a result in that case the dissenters regarded as deeply problematic. The loud calls for reform by the dissenters eventually persuaded the rest of the Court except for then-Justice Rehnquist. As the maps shows, this dialectic continues. Justice Rehnquist kept flying a flag against strong protection for commercial speech in Central Hudson (1980) and this flag was lifted again by the dissenters in 2011’s Sorrell decision.

Based on the reactions of my students, this standard visualization is easier to grasp than the Spaeth visualization. This makes sense to me — the Y-axis is certainly easier to interpret and the overall arc of the doctrine is easier to follow. While I too generally prefer standard visualizations, it is important to realize that, at this stage of development, they are far more labor-intensive to produce. By their very nature, Spaeth visualizations leverage the coding done by the Supreme Court Database team. Citations are also automatically generated using the CourtListener API. By contrast, creating standard maps requires the user (usually me!) to read the cases individually and tease out the relevant cites. I enter the data into the software manually and it then creates the visualization.

Of course, it is also possible to generate some of the map automatically and then manually enter additional information. This is exactly what I did with all the cases from Virginia Pharmacy Board onward. Once again, the lesson here is that while computer-assisted network analysis is extremely valuable and efficient, it cannot yet entirely substitute for human reading and editing. The level of complexity in Supreme Court doctrine is simply beyond the capacity of current algorithms to completely capture.

Very informative article.