In 2014, the late Justice Scalia concurred in judgment in a case called McCullen v. Coakley. Judgment was in fact unanimous — invalidating under the First Amendment a Massachusetts law which criminalized standing on a public road or sidewalk within thirty-five feet of a reproductive health care facility. Though satisfied with decision to strike down the law, Justice Scalia bucked at the means taken to the end. His concurrence opens with these words:

Today’s opinion carries forward this Court’s practice of giving abortion-rights advocates a pass when it comes to suppressing the free-speech rights of their opponents. There is an entirely separate, abridged edition of the First Amendment applicable to speech against abortion.

Justice Scalia then dropped a cite to the cases he saw as proving his point:

See, e.g., Hill v. Colorado, 530 U.S. 703 (2000); Madsen v. Women’s Health Center, Inc., 512 U.S. 753 (1994).

So what was Scalia talking about? Well, it turns out that this particular “separate, abridged edition” of First Amendment doctrine is extremely easy to map. And mapping this doctrine helps explain a little about the new tool the good folks at Free Law Project and I have recently released to the world and also helps explain a little about the underlying First Amendment controversy. Consider then two looks at the citation network.

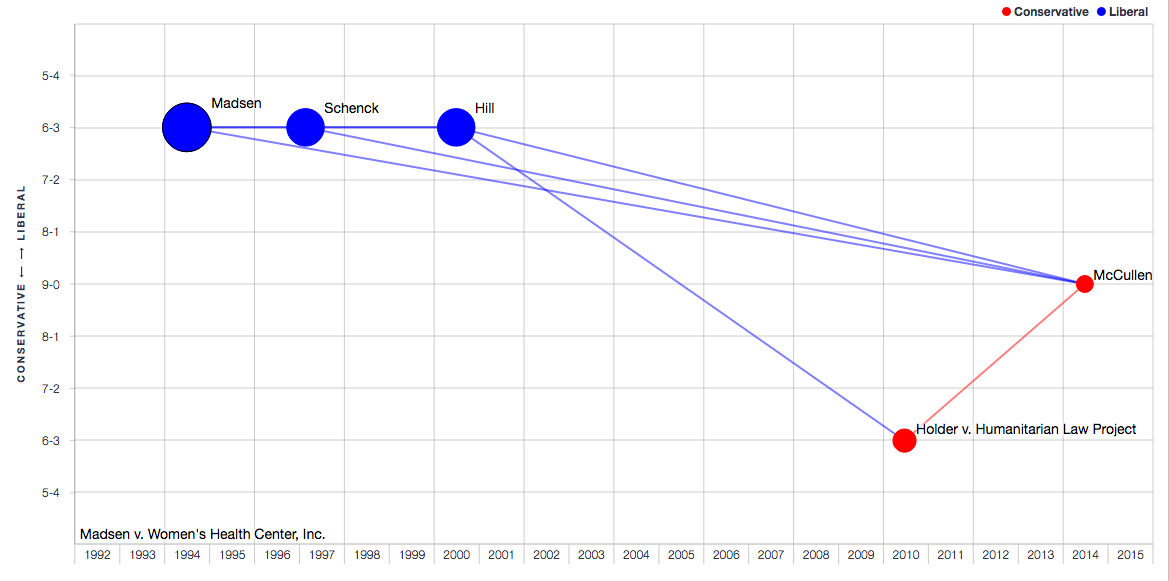

Every network created using the tool needs two endpoints — an “earliest case” and a “latest case.” The user must specify the endpoints. The screenshot above shows the basic three-degree network connecting McCullen v. Coakley and Madsen v. Women’s Health Center (click the image to open an interactive version in a separate window). In this instance, I chose McCullen as the latest case for the network because that’s the one with the key Scalia quote. I then chose Madsen as the earliest case because it was the earliest example Scalia cited as exemplifying the “abridged” First Amendment.

Purple circles on the map represent the endpoints. They are connected at 1-degree. This means that McCullen directly cites Madsen. The two red cases — Schenck v. Pro Choice Network of Western NY and Hill v. Colorado — represent 2-degree connections. Hill is a 2-degree connection because it links McCullen to Madsen at 2 degrees, i.e., McCullen cites Hill, which in turn cites Madsen. The 2-degree network picks up Hill since Scalia cited Hill as an example of an anti-abortion speech case. Hill cited Madsen since that was an earlier anti-abortion speech case. A similar logic explains the presence of Schenck in the network. Though Scalia failed to cite it, Schenck stands as another example of the phenomenon he laments. In that case, the Court upheld restrictions on anti-abortion speech against a First Amendment challenge. The tool picks up Schenck as a 2-degree case because Chief Justice Roberts cited it in his majority opinion (and of course, Schenck in turn cited Madsen).

The final case in the network is Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project. This is a 3-degree case because McCullen cites it (1), it cites Hill (2), and Hill in turn cites Madsen (3). What makes Humanitarian Law Project (HLP) interesting is that it is the only 3-degree case in the network. Although it was not an anti-abortion speech case, HLP did make an important pronouncement on content-basis analysis under the First Amendment. In his McCullen majority opinion, Chief Justice Roberts cited HLP to support his conclusion that the challenged Massachusetts law was not content-based”:

Whether petitioners violate the Act “depends” not “on what they say,” Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project, 561 U.S. 1, 27, 130 S.Ct. 2705, 177 L.Ed.2d 355, but on where they say it.

As it happens, this gets to the heart of Scalia’s disagreement with the majority’s analysis. By Scalia’s lights, the Massachusetts law was indeed content-based. He therefore thought that the Massachusetts law should be struck down under strict scrutiny (rather than under intermediate scrutiny as Chief Justice Roberts argued). At this point, it bears emphasis that all the justice in HLP agreed that the material-support-for-foreign-terrorist-organizations law was seen as content-based. However, the law actually survived strict scrutiny in a majority opinion written by Chief Justice Roberts and joined by Justice Scalia.

The map above depicts the same citation network as in the first map but using a schema that leverages data from the Supreme Court Database (Spaeth). The Y-axis in this second look tracks both the votes for outcome (9-0, 8-1, etc) and the decision direction (liberal/conservative) according to Spaeth.

This rendering of the network shows that all three of the initial anti-abortion speech cases — Madsen, Schenck, and Hill — had “liberal” results. On Spaeth’s coding, “liberal” decisions in this area are ones that upheld laws restricting anti-abortion speech. On the other hand, McCullen itself is coded as “conservative” because it struck down the law restricting anti-abortion speech.

I deliberately employed scare quotes in the paragraph above because Spaeth’s coding decisions are sometimes controversial — and often decisions coded as “liberal” or “conservative” do not fit with conventional understandings of those words. In this case, however, the Spaeth codes do align with conventional understanding. This is confirmed by HLP‘s classification as a “conservative” decision. In that case, as noted above, the material-support-for-foreign-terrorist-organizations survived strict scrutiny. As the map shows, that decision was a 6-3. All the conservative members of the Court joined the majority opinion, as did Justice Stevens.

In the end, analysis of this network reveals that First Amendment doctrine does not easily break down into “conservative” or “liberal” camps. Questions about content-basis and tiers of scrutiny are answered differently by justices who — in popular imagination at least — were viewed as coming from the same ideological camp. Readers interested in diving deeper into this interesting little corner of First Amendment theory should interact directly with the network on CourtListener. There you can tweak the looks, access to the full text of all the opinions, and examine the relevant Spaeth data. While you’re there, consider making your own new network!