Who’d a thunk it? The Orioles have the best record in the American League and retroactivity is batting a thousand at the Supreme Court this Term. It’s all very surprising.

This strange streak started back in January. In Montgomery v. Louisiana, the Court decided by a 6-3 vote that Miller v. Alabama‘s prohibition on Juvenile Life Without Parole (LWOP) applied retroactively. Then yesterday, the Court broke with custom and released the opinion on a Monday. In Welch v. United States, the justices agreed 7-1 on the suitability of retroactive application of Johnson v. United States‘s judgment that the Armed Career Criminal Act’s (ACCA) residual clause is unconstitutionally vague. Only Justice Thomas dissented.

How to grok what’s going on? Over at the Sentencing Law and Policy Blog, Professor Berman makes a compelling case that Montgomery and Welch are Teague make-up calls. In an age where just about everybody recognizes that there are just too many damn people in prison, perhaps zeitgeist demands the Court narrowly construe Teague‘s miserly limit. Though it conflicts with my natural pessimism, I like this line of thinking. Let’s look a little closer.

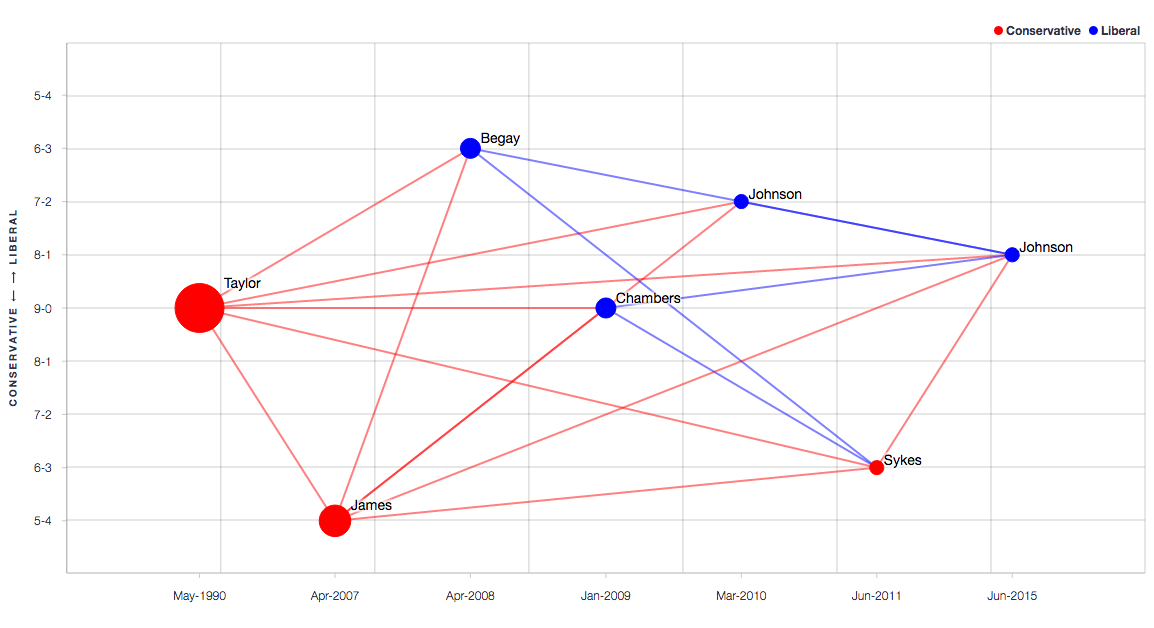

Figure 1 above shows 2-degree citation network connecting last Term’s Johnson decision back to the Court’s first ACCA case, 1990’s Taylor v. United States. (To see an interactive version of the map, click the image). As Justice Alito noted in his Johnson dissent, the majority’s decision in that case is probably best seen as the culmination of a long campaign spearheaded by Justice Scalia to rid the ACCA of its residual clause. Per Alito, the campaign began with Scalia’s dissent in James and continued with his dissent is Sykes. Alito may have bemoaned the Court’s infidelity to stare decisis in Johnson, but Justice Scalia’s war had been waged in plain sight and his reasoning finally won the day.

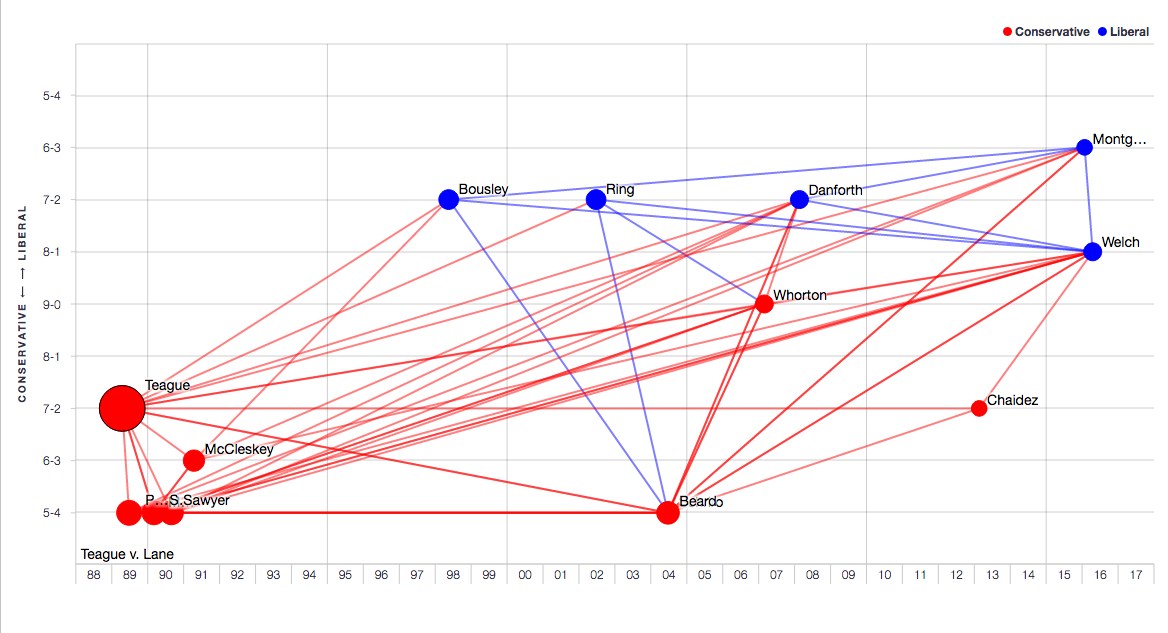

Figure 2 shows the 2-degree citation network connection Welch back to Teague. This means that is shows all the cases cited in Welch that in turn cited Teague. (Once again, you can view an interactive version of the map by clicking the image). Though Justice Alito dissented in Johnson, he did not do so in Welch. This is interesting to me because Alito joined Justice Scalia’s dissent in Montgomery decrying retroactive application of Miller. And Justice Thomas dissented from the narrowing of Teague in both Montgomery and Welch. In other words, it appears that Justice Alito “switched” on retroactivity even though he had strong views on the incorrectness of Johnson itself.

To me, this is additional prima facie evidence of the new reality on Teague retroactivity doctrine noted by Professor Berman. Justice Alito professes support for stare decisis and it seems that he now respects the force of Montgomery even though he disagreed with that decision when it came down. No doubt there are other ways to read these tea leaves, but it’s hard not to feel heartened by two retroactive applications in a row of constitutional decisions that were themselves hotly contested.