This week I start teaching First Amendment law for the very first time. It should be great fun. For the class textbook, I have adopted Kathleen Sullivan & Noah Feldman, First Amendment Law (5th Ed). (This textbook is basically just the last 750 pages of Sullivan & Feldman, Constitutional Law (18th Ed.)). As I prepped the first line of cases explored in the text — “clear and present danger” from Schenck (1919) to Brandenburg (1969) — it occurred to me that the textbook’s materials could be usefully mapped and hyperlinked.

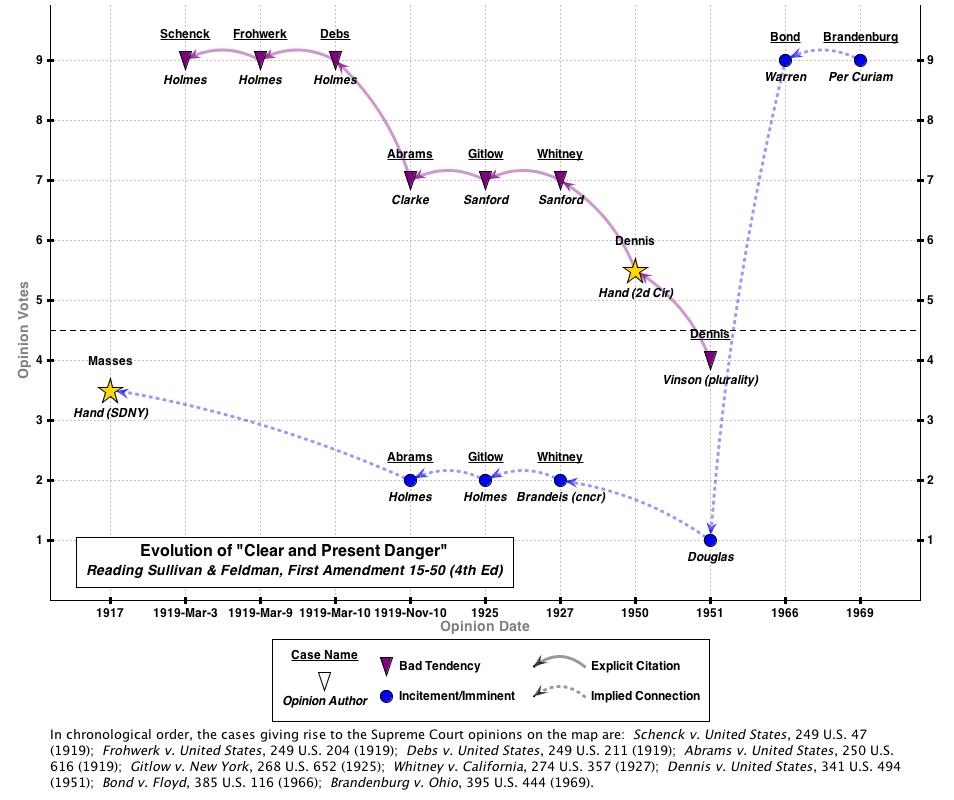

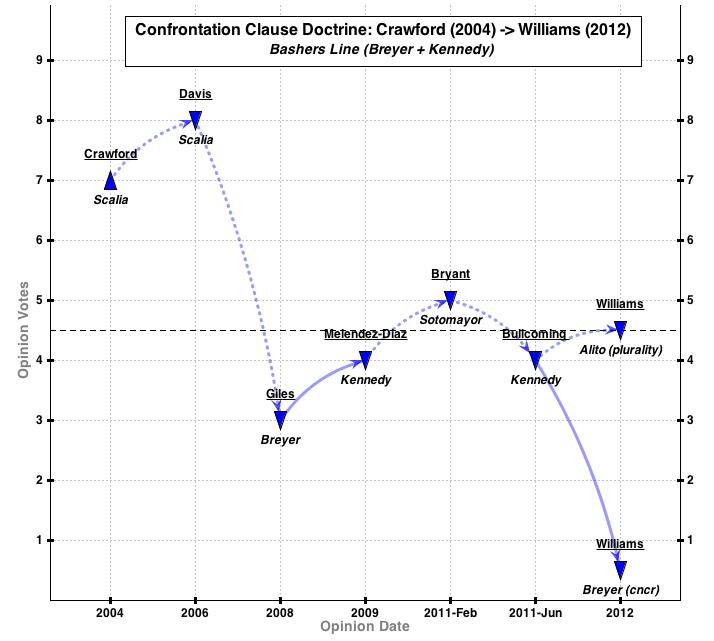

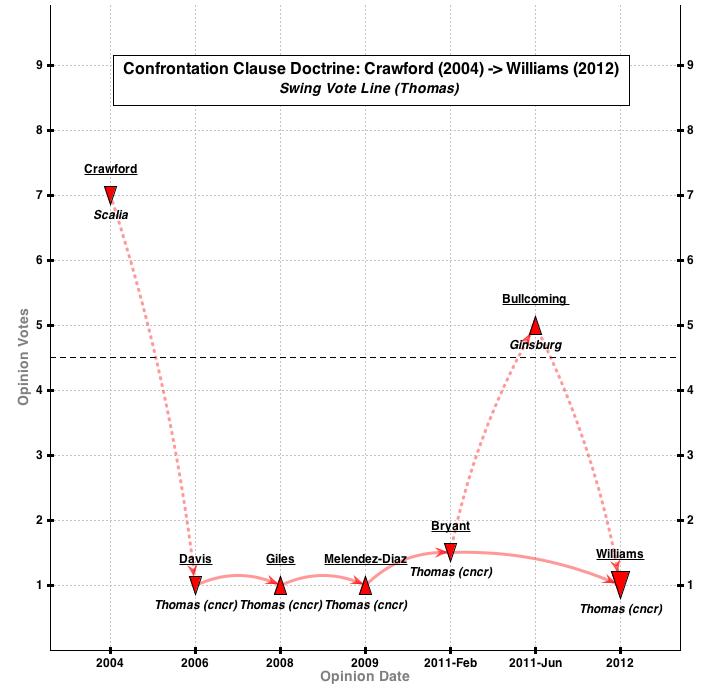

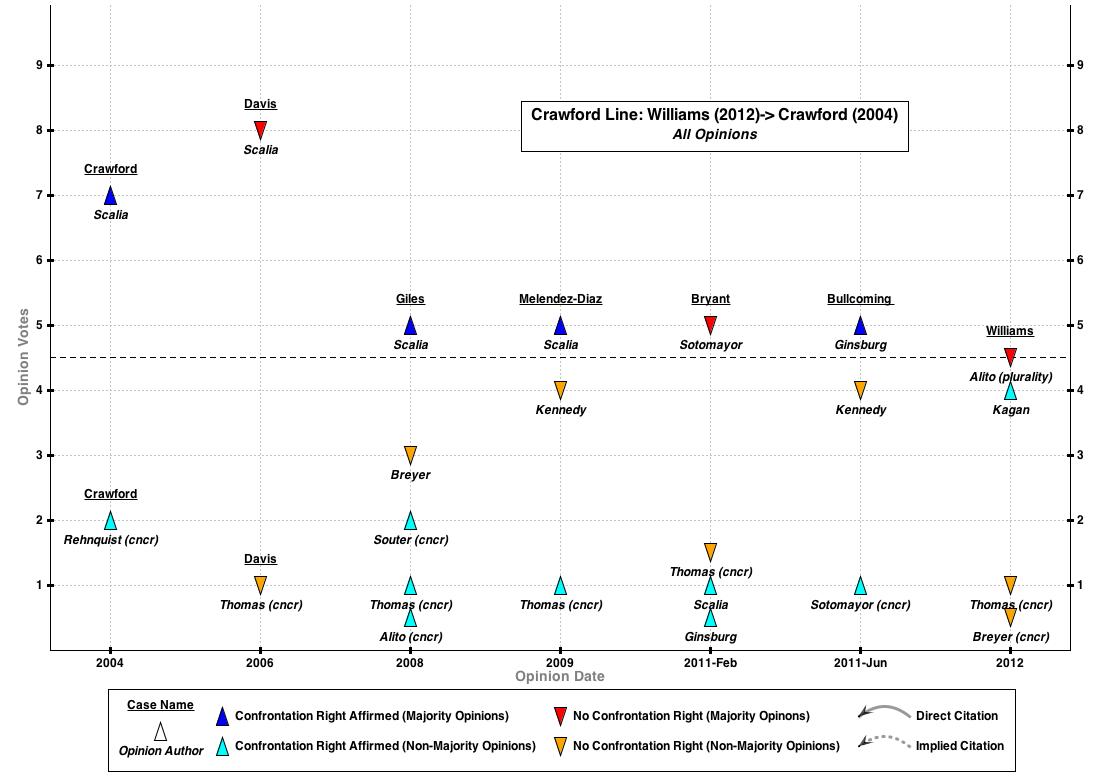

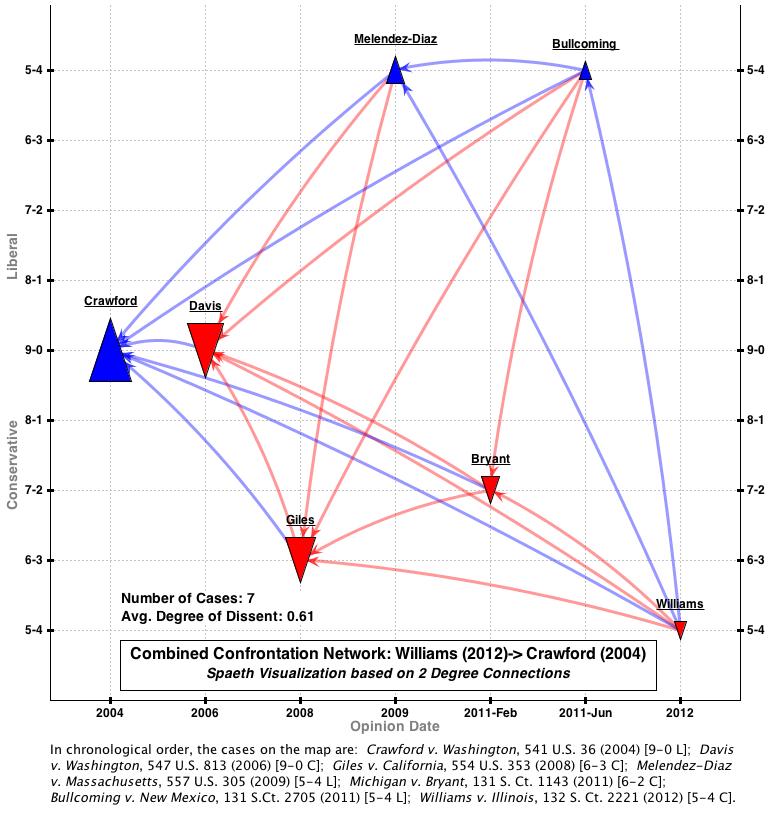

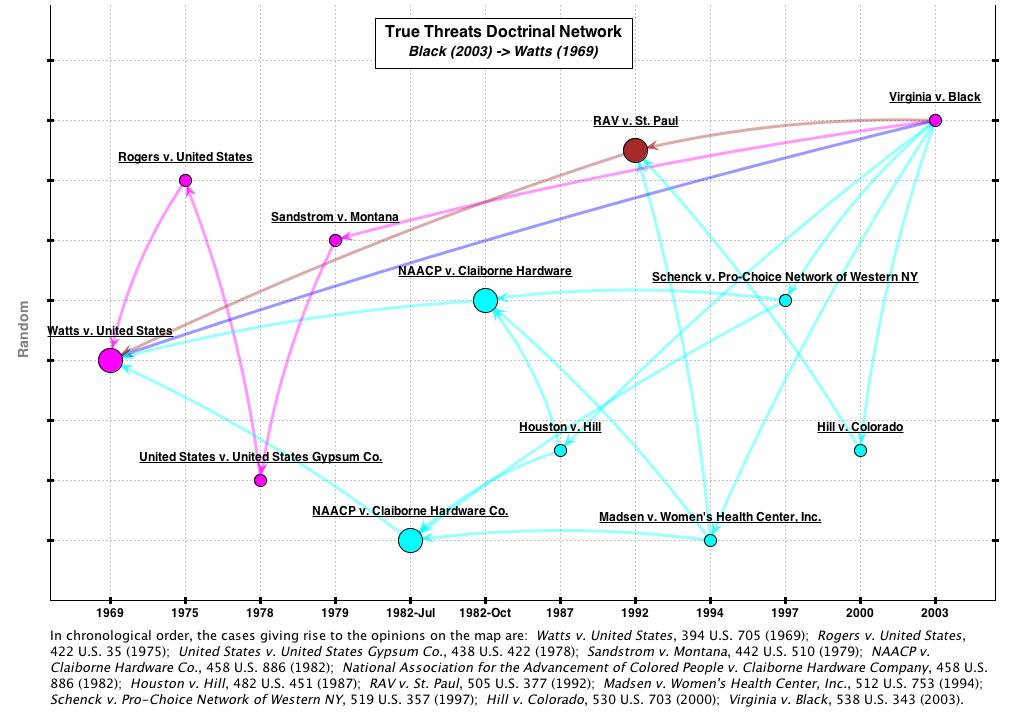

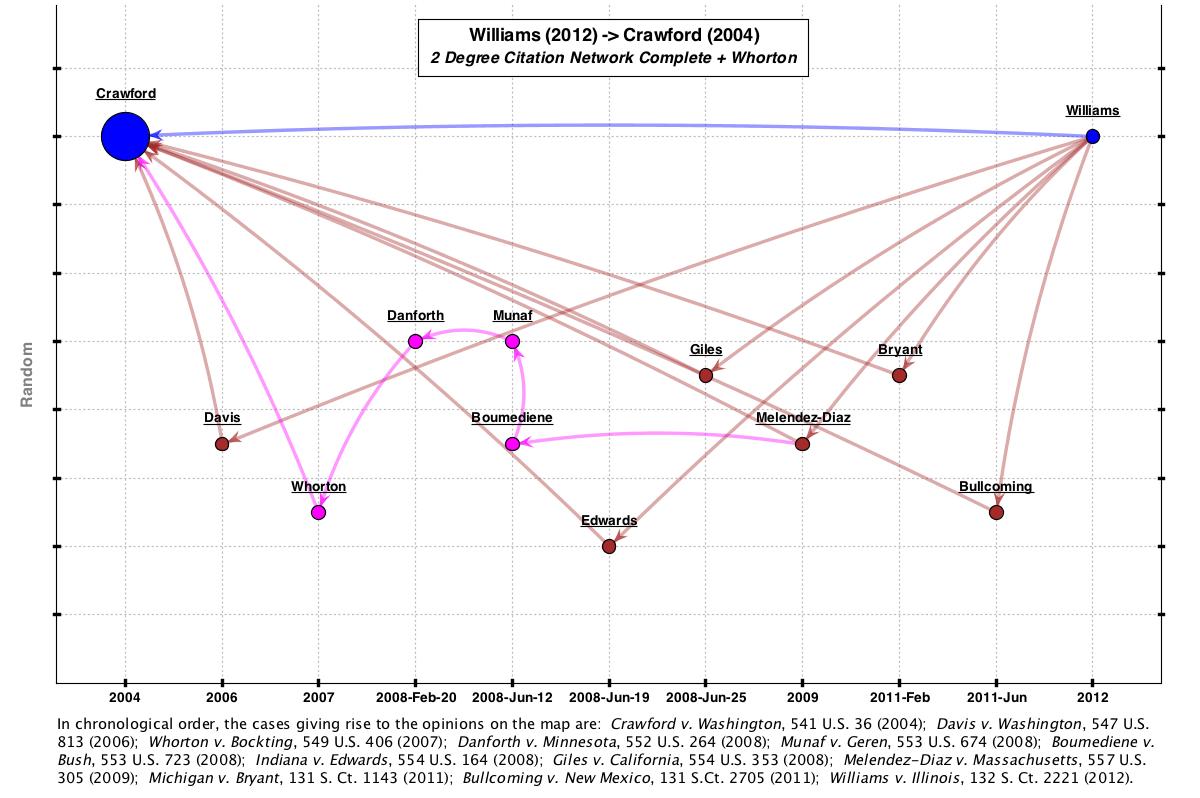

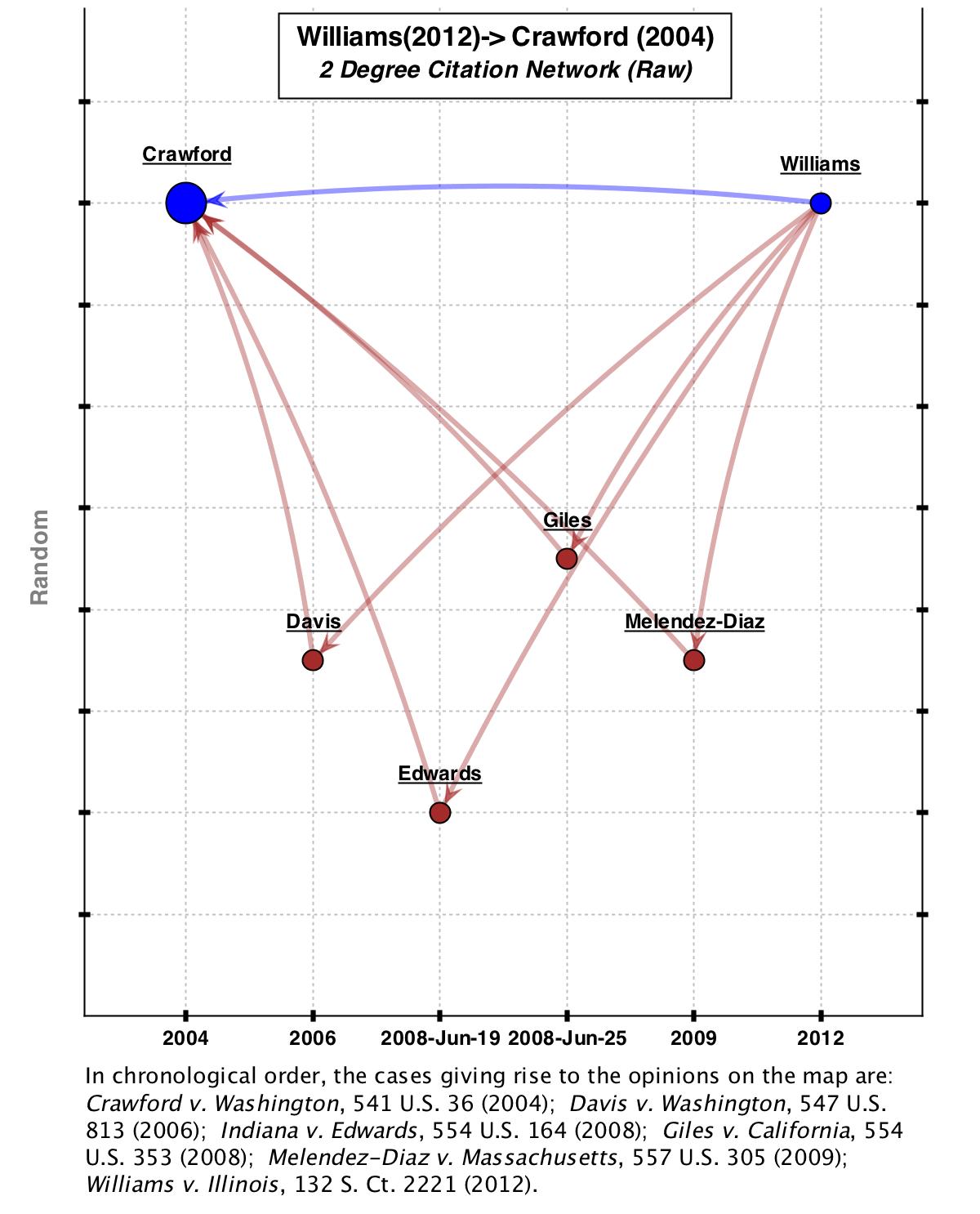

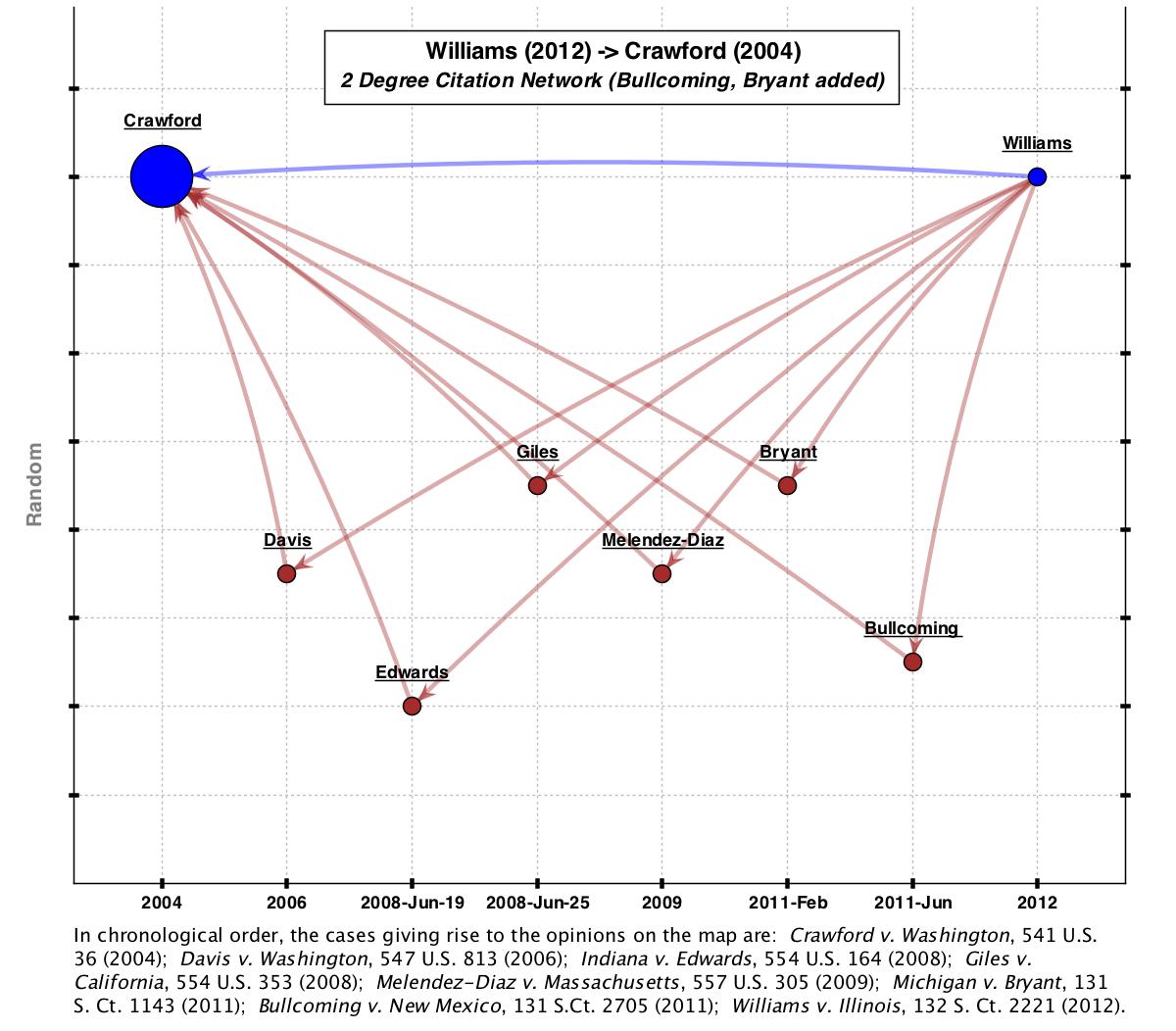

The map above represents my initial attempt at charting the clear-and-present danger cases discussed from pages 15-50 of the Sullivan & Feldman text (pp. 899-934 of Con Law 18th Ed). Briefly, I interpret the doctrine during this period as having two competing lines of opinions. The dominant line (represented by purple downward-facing triangles) permitted suppression of speech if it promoted “bad tendencies” in audiences. The dissenting tradition (represented by blue circles) advocated a more permissive standard for free speech, permitting suppression only where the speech imminently incited unlawful conduct. The “bad tendency” line effectively held sway until Brandenburg redeemed the famous early dissents of Holmes and Brandeis.

At this juncture, I am less interested in discussing the content of the map than its form (in my next post, I’ll return to the substance and make a First Amendment argument). In this map, I am experimenting with a potential way to “deliver” Con Law textbooks or perhaps online supplements. Though the map above looks like a standard SCOTUS doctrinal map — Y axis shows votes for an opinion, etc — if you click on the image above and then click on the opinions, you’ll see something different.

What I’ve done is simple. Each opinion links to a page that features discussion of the opinion as prompted by the Sullivan & Feldman text. The page also contains links to other resources such as the full opinion text via CourtListener, oral argument and summary via Oyez, political science data via the Supreme Court Database, and other historical and contextual information via Wikipedia. Go on, try it out! I’ll wait…

Admittedly, my execution at this point is very rudimentary. I created the opinion drop pages using Word’s html editor. So it could look a lot prettier. And the content could use editing for sure. But I’ll confessing to liking the overall idea. The map basically serves as a way to organize a hyperlinked textbook portion. Given that so much of Con Law turns on lines of Supreme Court cases, it seems to me that this form might have broader application. At least visual learners might appreciate seeing the big picture while working their way through the edited texts.

The proof, I suppose, is in the pudding. I will direct my new students to this map when the semester starts and report back on how they react. Meanwhile, and as always, I’d love to hear any comments or ideas from readers. Could this form work to aid teaching con law?