By Adam Stone

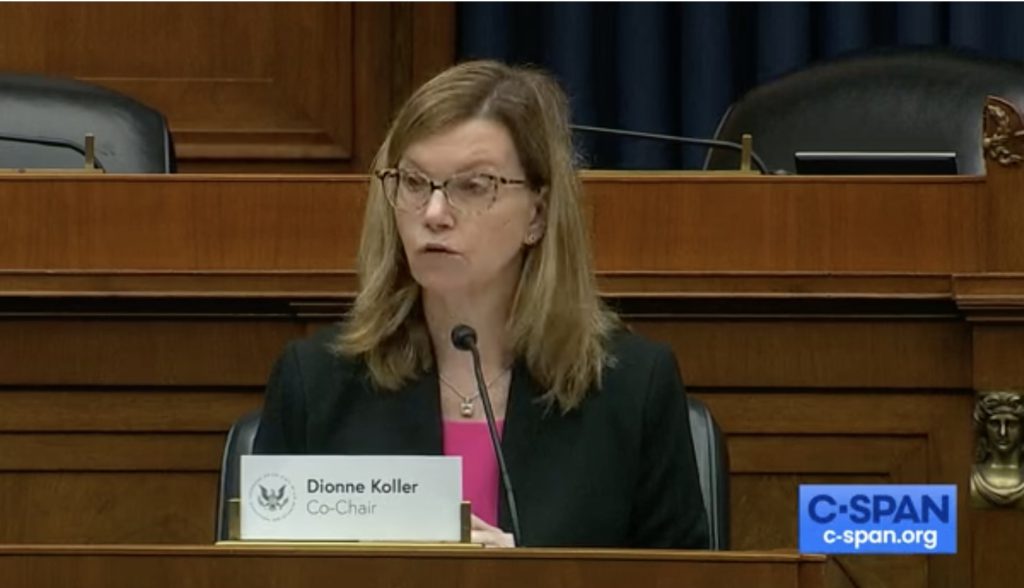

A gymnast in her youth, Dionne Koller knew intuitively what her career in the legal-academic world would look like.

“Sports was a very important part of my life experience. When I got into academia, that led me to have an interest in sports law, to see what sports law was all about,” she says.

But is there even such a thing as “sports law”? When Koller joined the UBalt Law faculty in 2006, the answer was a definite maybe. Since then, she has helped to put sports law on the map, and earned a reputation as one of the leading scholars in the field.

An emerging discipline

In the early 2000s, sports law wasn’t fully recognized within the legal academy as a separate academic discipline. “People would say: Certainly, there’s a lot of law that applies to sports — antitrust law, labor law, contract law. We apply a lot of law to sports, but there’s not a lot of law about sports,” Koller says.

Others took a different view. There were legal scholars who felt there was important work to be done to make sports law a field. Koller saw a professional window open up in that transitional moment. “My personal love for sports intersected with an opportunity to really take on important issues,” she says.

“When the University of Baltimore hired me, I made clear that I would want to go up for tenure with a sports law portfolio, that my scholarly record would be built on sports law and not some other recognized area,” she says.

She’s gone on to do just that, addressing urgent issues, especially around youth participation in sports. She was quoted widely when Larry Nassar, the former U.S. Women’s Gymnastics team doctor, was convicted of abusing hundreds of athletes. She recently co-chaired the Congressional Commission on the State of United States Olympics and Paralympics, and she was a member of the Aspen Institute Sport and Society’s Children’s Rights in Sports Work Group.

When it comes to youth sports, she says, there is much that needs fixing, and colleagues say Koller is uniquely qualified to drive those changes.

“She has been a pioneer in her teaching and her scholarship,” says Prof. Margaret Johnson, co-director of UBalt Law’s Center on Applied Feminism and director of the Bronfein Family Law Clinic.

Johnson notes that Koller has won the UBalt President’s Award for her teaching, scholarship and service, and has been recognized with the Association of American Law Schools’ 2024 award for significant contributions to the field of sports law.

“She models professionalism, hard work and commitment,” Johnson says. In her work at the law school, “She sees everyone for who they are, in a way that makes everyone feel good about being together in this shared enterprise.”

Focus on Youth

Koller’s first book, More Than Play: How Law, Policy, and Politics Shape American Youth Sport, is due out in 2025.

“The book mirrors my approach to sports law generally, which is to take something that we take for granted and illuminate areas that we maybe haven’t been paying attention to,” she says. The book challenges the unspoken assumption “that youth sport is good, it’s healthy, every kid should participate.”

The truth is somewhat more nuanced, she argues.

From a legal standpoint, there’s an operating assumption that sports should not be regulated. That has real-world impact. “We’re over-training kids, overworking them, burning them out. It has physical consequences, and it has mental consequences,” she says.

While Koller doesn’t lay out a program for fixing all this, she has some strong thoughts on the subject, guided in part by her understanding of how sports in other countries are regulated.

“There are countries like Norway that do things very, very differently,” she says. “They give children some rights, meaning children can decide how much time they’re going to spend on their sport. They’re going to decide if they want to travel to compete. Children have some say.”

A better system would also reflect the fact that “parents can’t always be neutral judges or arbiters of their children’s youth sport experience,” she says. “Parents get swept away in their children’s performances and youth sport experiences. They lose that healthy mental distance they might be able to use in other contexts.”

That’s an argument for more government regulation. Koller would like to see a national standard, with “baseline levels for safety, including regulations for those who coach, making sure that there are background checks, that there are minimum competencies that coaches have to possess,” she says.

That’s easier said than done.

There’s a general mindset that government has no place regulating the creative and competitive world of athletics. “That might make sense when you’re talking about professional football, where athletes are protected by their union. But to take that mentality and apply it to youth sports is problematic,” she says.

At the same time, parents’ rights advocates are for the most part in knee-jerk opposition to government involvement in youth sports. But the idea here isn’t to rob parents of their decision-making authority, Koller says: It’s to protect the kids.

“I regularly hear from parents who are shocked that nobody’s regulating this or making sure the coach has any ability to coach,” she says. “The government doesn’t need to run Little League in order to set some minimum safety standards for the people who do run Little League.”

As Koller looks to elevate these issues within the legal community, and with the public at large, she expresses gratitude to UBalt Law for giving her the freedom to pursue this once-unrecognized field.

“I have been able to do this scholarship because of the University of Baltimore law school’s support,” she says. “Because the University of Baltimore believed in me, I’ve really been able to develop as a scholar, and to contribute to the field. All of that is a result of the University of Baltimore’s standing behind me and encouraging me. I have the career that I have because of this institution.”

Adam Stone is a writer based in Annapolis.

Photo by Larry Canner.