By Hope Keller

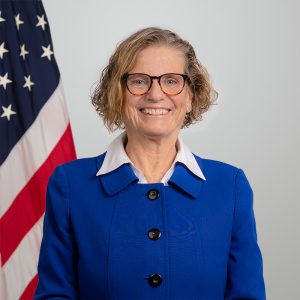

Tracey Forfa, J.D. ’91, was named the director of the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine in February 2023, becoming the first non-veterinarian to hold the position. The center regulates food, drugs and medical devices for pets, as well as for animals that produce meat, milk and eggs.

She is in good company at the center, which has been hiring lawyers regularly over the past several years, says Forfa, who has been with the FDA since 1993 and at the center since 2002.

“We have inside jokes that for every veterinarian or veterinary technician we hire, we hire another lawyer,” she says. “But all kidding aside, this is a good time to be a lawyer heading the center. There’s a lot going on.”

The law that gave the FDA its regulatory authority – the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938 – poses one of the greatest challenges to the agency, says Forfa. Designed to establish quality standards for food, drugs, medical devices and cosmetics made in the United States, the law has been amended over the years, but not often enough, she adds.

“We’re regulating products in 2023 using basically the same fundamental 1938 authorities that we were given by Congress,” Forfa says. “That is one of the reasons that I believe that my law degree is so foundational, to be able to help move the center into 2023 and beyond.”

One of Forfa’s current priorities is working with Congress on legislation to change the way the center reviews feed additives that address fundamental problems such as climate change.

“Under our existing authorities, we would have to regulate (feed additives) as a drug product,” Forfa says, explaining that the process would be lengthy. “We are looking for flexibilities within our existing framework, to be able to bring innovative products to market as quickly as possible, because we see them as the future of animal health and public health.”

‘We have inside jokes that for every veterinarian or veterinary technician we hire, we hire another lawyer.’

Certain feed additives would reduce the amount of methane that cattle produce during digestion. While cow burps might sound innocuous, they in fact contain a significant amount of methane that contributes to global warming.

“(Congress) in no way ever envisioned this type of product to address this type of problem,” Forfa says of the authorities granted the FDA in 1938.

She emphasized the center’s commitment to the FDA’s “One Health” strategy, which focuses on the intersection of human, animal and environmental health.

“Some things we discovered on the animal side impact both human medicine and the environment — certainly the methane reduction is an example of that,” she says.

Another primary concern for Forfa and the Center for Veterinary Medicine is the misuse of xylazine, an animal tranquilizer that is increasingly being mixed with street drugs such as fentanyl. The drug, intended for veterinary use, particularly in large animals, can cause gangrenous wounds in human users.

While the center has mechanisms in place to withdraw an animal drug if safety concerns are raised about its appropriate use, the inappropriate use of xylazine by humans is “an anomaly for us,” says Forfa.

“It remains a really important drug product for veterinarians, particularly veterinarians who work in the large-animal sector,” she says. “Imagine not being able to sedate a 1,000-pound cow who’s trying to kill you as you’re working on it.”

The Center for Veterinary Medicine has joined with the Drug Enforcement Administration and other agencies to help flag and examine imported shipments of the drug.

“It’s an all-government response, from the White House all the way through all of the agencies involved, including local law enforcement,” Forfa says. “We’re all extremely concerned about the horrific effects that happen when xylazine is combined with fentanyl.”

Hope Keller is a writer based in Connecticut.