Volume 84 of the Tennessee Law Review features an article entitled “The Persistence of the Confederate Narrative” by Peggy Cooper Davis, Aderson Francois, and Colin Starger. The article has a special online Companion Atlas that you can find here.

Persistence of the Confederate Narrative – Atlas Now Online

Fourth Amendment Atlas Now Available

Interested in Fourth Amendment doctrine? Check out this Fourth Amendment Doctrinal Atlas!

CALI, Coding, and a Network Viewing Experiment

Last week I attended my first CALI conference — CALIcon16 at Georgia State University School of Law. Props to the organizers for putting together such an excellent program! For those that don’t know already, CALI is the Center for Computer-Assisted Legal Instruction and it’s a pretty amazing outfit. Standing at a critical intersection between legal technology, educational theory, and access-to-justice, CALI sponsors tremendous innovation in teaching and learning while promoting great social values.

Since CALI is also one of the few gatherings where you’re likely to encounter law professors that code, I decided to dip my own toes into the bitstream. I’ve been slowly trying to learn the basics of HTML, CSS, and Javascript over the past year. (This has also meant trying to come to terms with frameworks like Bootstrap and JQuery and getting used to the Sublime text editor and Chrome’s developer tools. Coding these days seems to mean swimming in environment soup…) And I presented the results of my fledgling coding efforts in my CALIcon16 talk.

Specifically, I put together a four webpages designed to showcase SCOTUS Maps created with the free tool hosted on CourtListener. Each page focuses on a basic network theme and is designed to permit the visitor to switch easily between maps that demonstrate that theme. One page highlights small SCOTUS networks. Another looks at big SCOTUS networks. A third page gives examples of low dissent networks. And the final page features high dissent networks. I’m not sure if this format worked well for others, but I liked it. If folks are interested in looking at networks through this lens, follow the links above and judge for yourselves! As always, I’d love to hear feedback.

Meanwhile, if you’d like to watch my entire talk in which I explain the CourtListener tool and the overall SCOTUS Mapping Project, check out the link to my entire talk right here.

The Big Picture: 2014 and 2015 Term Collections

Every year, a few Supreme Court cases make big headlines. Headline cases generally involve major constitutional issues or key disputes between actors on the socio-political stage or some other kind of drama that rivets the attention of the mainstream media. Such media attention can help educate the public of important legal issues, but it can also distort public perception of the Court. For the truth is that most cases decided by the Court every year do not burn with drama. Considered as a whole, the Court’s yearly docket trends obscure and dry. Yet for SCOTUS die hards, even non-headline case material is fascinating.

If you are a die-hard, then you should check out two collections of doctrinal networks that we curate here at the SCOTUS Mapping Project. These collections give you a way to see the big picture of the Court’s docket — not just the headline grabbing major cases (though the networks can help you with those cases too). The first collection covers every case decided by the Court in its 2014 Term. The second collection covers the current 2015 Term — and it is regularly updated as the Court releases new opinions.

The two collections follow the same basic format. The collection is a sortable table where each row represents one case decided in the 2014 or 2015 Term. For each case, a doctrinal network has been created by connecting the new SCOTUS case to an earlier one (the “network anchor”). Links to the doctrinal network saved on CourtListener are provided, as are links to the relevant SCOTUSBlog entry for each case. Each row names the law at issue in a particular case and also features data on the size and degree of dissent for the doctrinal network.

The only formal difference between the 2014 Term collection and the 2015 Term collection concerns scope. I defined the 2014 Term collection based on all the cases from that term that were coded by the Supreme Court Database (aka Spaeth) — 71 cases. Since the Spaeth entries for the current 2015 Term are not yet available, I am simply creating a network for every opinion released by the Court on its 2015 Term Opinions webpage. (This difference in scope has resulted in a few anomalies in the 2015 Term collection for in cases when the Court releases one-line “opinions.” Such opinions — like those where the judgment below is affirmed by an equally divided Court or where the writ of certiorari is dismissed as improvidently granted — do not cite precedent and cannot be used to create a doctrinal network.)

Between the two collections, there are now over 100 maps of SCOTUS doctrinal networks. Some networks are very small — such as the two-case network in the 2015 Term case OBB Personenverkehr. Some networks are YUGE — such as the 68-case network from last Term’s Obergefell blockbuster. Whether small, large, or somewhere in between, the choice of network anchor is justified in the “Description” field for each network so that readers can judge for themselves the validity and/or usefulness of the precedent map. And of course, the network also provides direct links the the full text of all opinions and to the Spaeth entry for all the cases (barring the as-yet uncoded 2015 Term cases themselves).

In short, there is plenty to look at and explore. Please let me know if you have questions, comments, or ideas about how to improve these collections.

Grokking Welch

Who’d a thunk it? The Orioles have the best record in the American League and retroactivity is batting a thousand at the Supreme Court this Term. It’s all very surprising.

This strange streak started back in January. In Montgomery v. Louisiana, the Court decided by a 6-3 vote that Miller v. Alabama‘s prohibition on Juvenile Life Without Parole (LWOP) applied retroactively. Then yesterday, the Court broke with custom and released the opinion on a Monday. In Welch v. United States, the justices agreed 7-1 on the suitability of retroactive application of Johnson v. United States‘s judgment that the Armed Career Criminal Act’s (ACCA) residual clause is unconstitutionally vague. Only Justice Thomas dissented.

How to grok what’s going on? Over at the Sentencing Law and Policy Blog, Professor Berman makes a compelling case that Montgomery and Welch are Teague make-up calls. In an age where just about everybody recognizes that there are just too many damn people in prison, perhaps zeitgeist demands the Court narrowly construe Teague‘s miserly limit. Though it conflicts with my natural pessimism, I like this line of thinking. Let’s look a little closer.

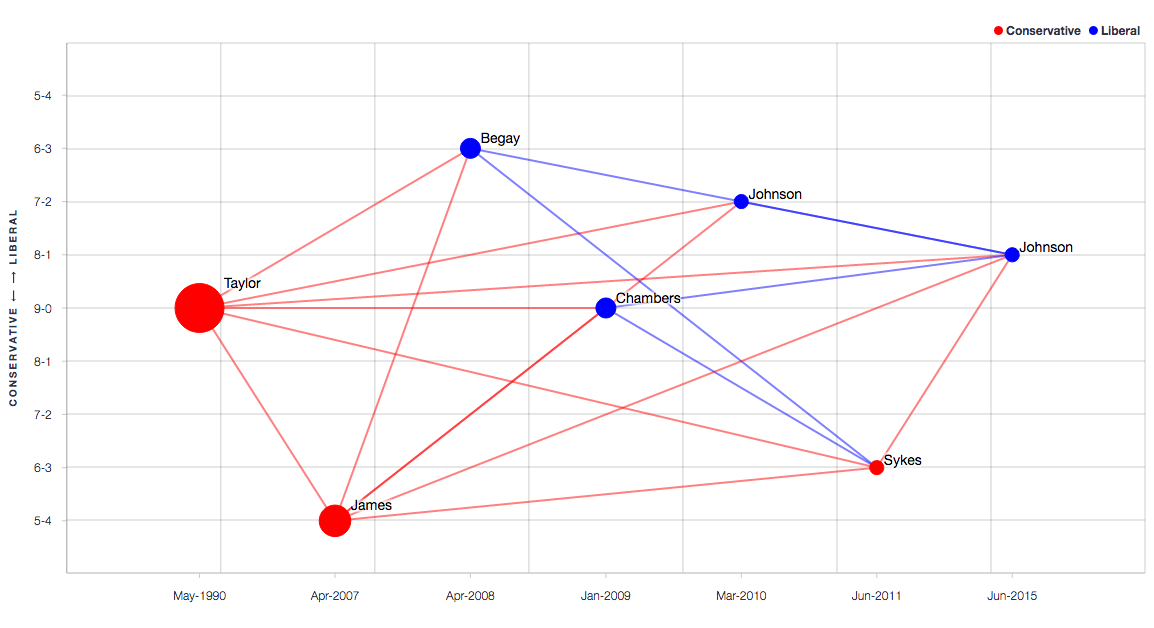

Figure 1 above shows 2-degree citation network connecting last Term’s Johnson decision back to the Court’s first ACCA case, 1990’s Taylor v. United States. (To see an interactive version of the map, click the image). As Justice Alito noted in his Johnson dissent, the majority’s decision in that case is probably best seen as the culmination of a long campaign spearheaded by Justice Scalia to rid the ACCA of its residual clause. Per Alito, the campaign began with Scalia’s dissent in James and continued with his dissent is Sykes. Alito may have bemoaned the Court’s infidelity to stare decisis in Johnson, but Justice Scalia’s war had been waged in plain sight and his reasoning finally won the day.

Figure 2 shows the 2-degree citation network connection Welch back to Teague. This means that is shows all the cases cited in Welch that in turn cited Teague. (Once again, you can view an interactive version of the map by clicking the image). Though Justice Alito dissented in Johnson, he did not do so in Welch. This is interesting to me because Alito joined Justice Scalia’s dissent in Montgomery decrying retroactive application of Miller. And Justice Thomas dissented from the narrowing of Teague in both Montgomery and Welch. In other words, it appears that Justice Alito “switched” on retroactivity even though he had strong views on the incorrectness of Johnson itself.

To me, this is additional prima facie evidence of the new reality on Teague retroactivity doctrine noted by Professor Berman. Justice Alito professes support for stare decisis and it seems that he now respects the force of Montgomery even though he disagreed with that decision when it came down. No doubt there are other ways to read these tea leaves, but it’s hard not to feel heartened by two retroactive applications in a row of constitutional decisions that were themselves hotly contested.

Scalia’s Lament: Two Looks at Anti-Abortion Speech Doctrine

In 2014, the late Justice Scalia concurred in judgment in a case called McCullen v. Coakley. Judgment was in fact unanimous — invalidating under the First Amendment a Massachusetts law which criminalized standing on a public road or sidewalk within thirty-five feet of a reproductive health care facility. Though satisfied with decision to strike down the law, Justice Scalia bucked at the means taken to the end. His concurrence opens with these words:

Today’s opinion carries forward this Court’s practice of giving abortion-rights advocates a pass when it comes to suppressing the free-speech rights of their opponents. There is an entirely separate, abridged edition of the First Amendment applicable to speech against abortion.

Justice Scalia then dropped a cite to the cases he saw as proving his point:

See, e.g., Hill v. Colorado, 530 U.S. 703 (2000); Madsen v. Women’s Health Center, Inc., 512 U.S. 753 (1994).

So what was Scalia talking about? Well, it turns out that this particular “separate, abridged edition” of First Amendment doctrine is extremely easy to map. And mapping this doctrine helps explain a little about the new tool the good folks at Free Law Project and I have recently released to the world and also helps explain a little about the underlying First Amendment controversy. Consider then two looks at the citation network.

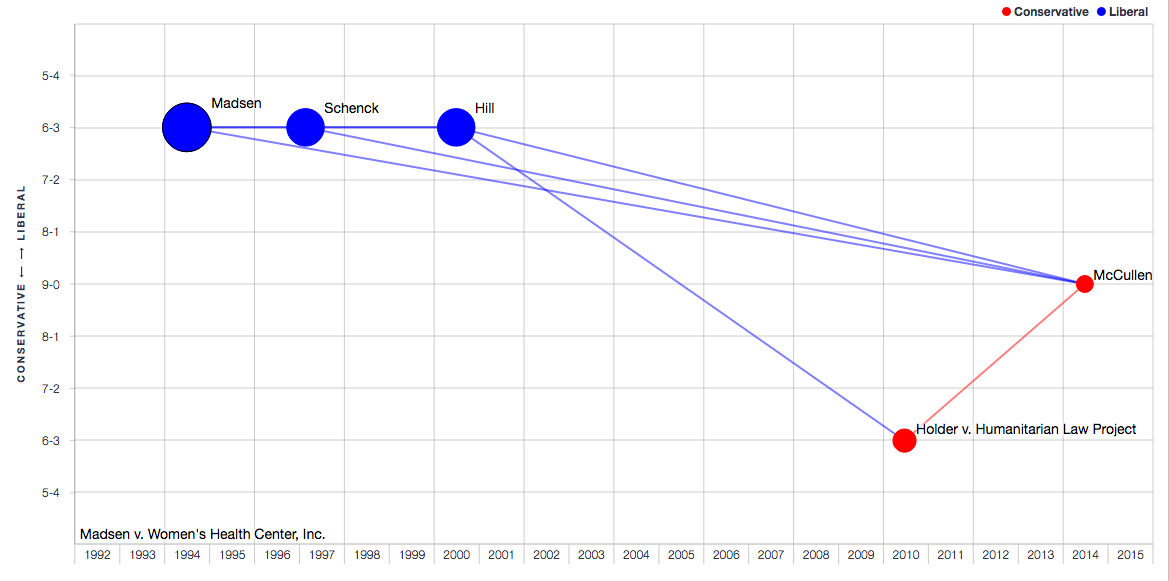

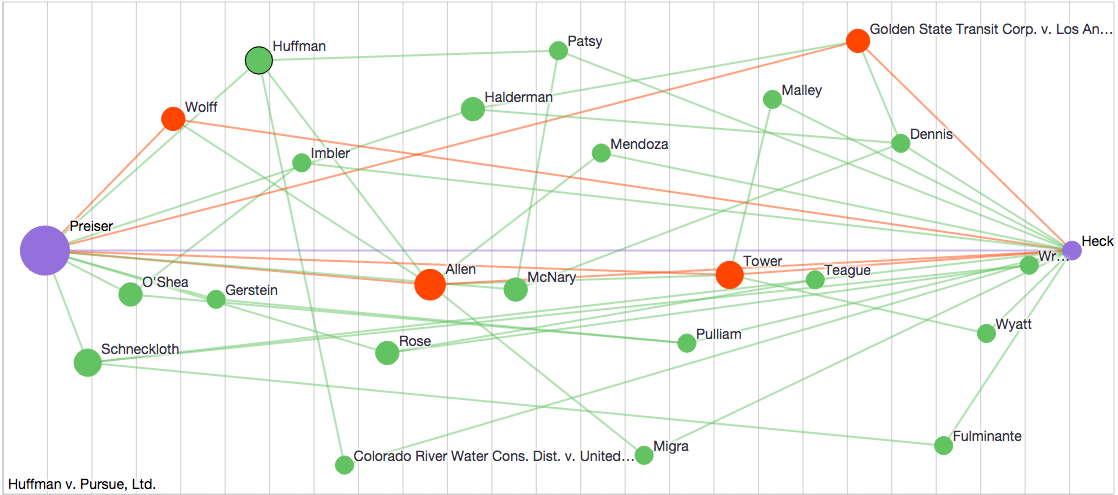

Every network created using the tool needs two endpoints — an “earliest case” and a “latest case.” The user must specify the endpoints. The screenshot above shows the basic three-degree network connecting McCullen v. Coakley and Madsen v. Women’s Health Center (click the image to open an interactive version in a separate window). In this instance, I chose McCullen as the latest case for the network because that’s the one with the key Scalia quote. I then chose Madsen as the earliest case because it was the earliest example Scalia cited as exemplifying the “abridged” First Amendment.

Purple circles on the map represent the endpoints. They are connected at 1-degree. This means that McCullen directly cites Madsen. The two red cases — Schenck v. Pro Choice Network of Western NY and Hill v. Colorado — represent 2-degree connections. Hill is a 2-degree connection because it links McCullen to Madsen at 2 degrees, i.e., McCullen cites Hill, which in turn cites Madsen. The 2-degree network picks up Hill since Scalia cited Hill as an example of an anti-abortion speech case. Hill cited Madsen since that was an earlier anti-abortion speech case. A similar logic explains the presence of Schenck in the network. Though Scalia failed to cite it, Schenck stands as another example of the phenomenon he laments. In that case, the Court upheld restrictions on anti-abortion speech against a First Amendment challenge. The tool picks up Schenck as a 2-degree case because Chief Justice Roberts cited it in his majority opinion (and of course, Schenck in turn cited Madsen).

The final case in the network is Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project. This is a 3-degree case because McCullen cites it (1), it cites Hill (2), and Hill in turn cites Madsen (3). What makes Humanitarian Law Project (HLP) interesting is that it is the only 3-degree case in the network. Although it was not an anti-abortion speech case, HLP did make an important pronouncement on content-basis analysis under the First Amendment. In his McCullen majority opinion, Chief Justice Roberts cited HLP to support his conclusion that the challenged Massachusetts law was not content-based”:

Whether petitioners violate the Act “depends” not “on what they say,” Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project, 561 U.S. 1, 27, 130 S.Ct. 2705, 177 L.Ed.2d 355, but on where they say it.

As it happens, this gets to the heart of Scalia’s disagreement with the majority’s analysis. By Scalia’s lights, the Massachusetts law was indeed content-based. He therefore thought that the Massachusetts law should be struck down under strict scrutiny (rather than under intermediate scrutiny as Chief Justice Roberts argued). At this point, it bears emphasis that all the justice in HLP agreed that the material-support-for-foreign-terrorist-organizations law was seen as content-based. However, the law actually survived strict scrutiny in a majority opinion written by Chief Justice Roberts and joined by Justice Scalia.

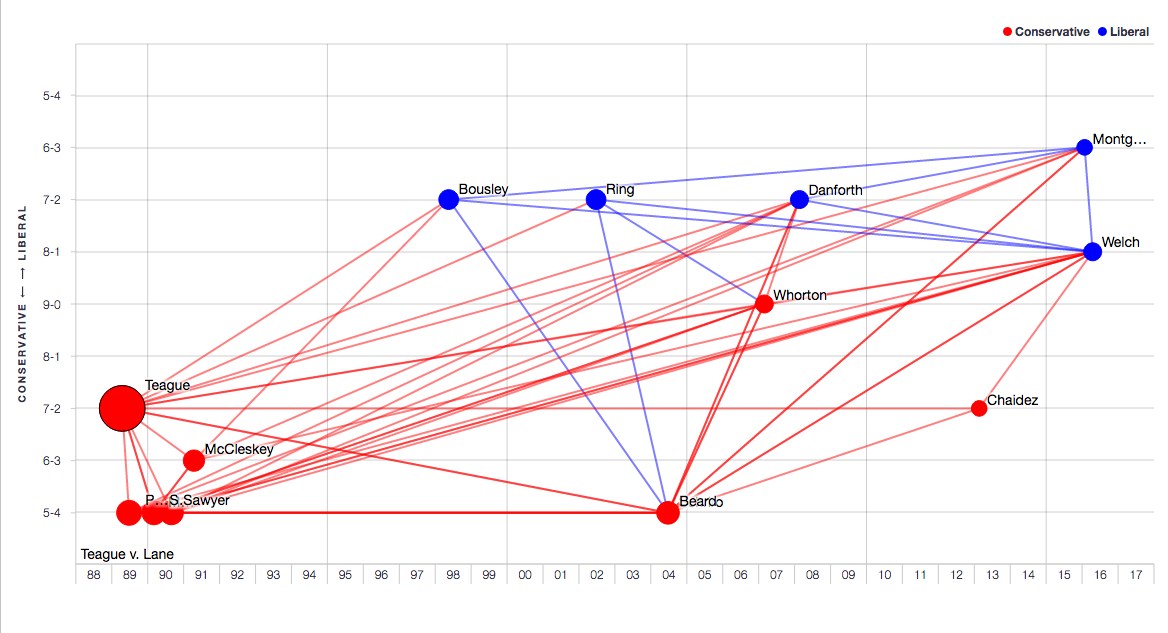

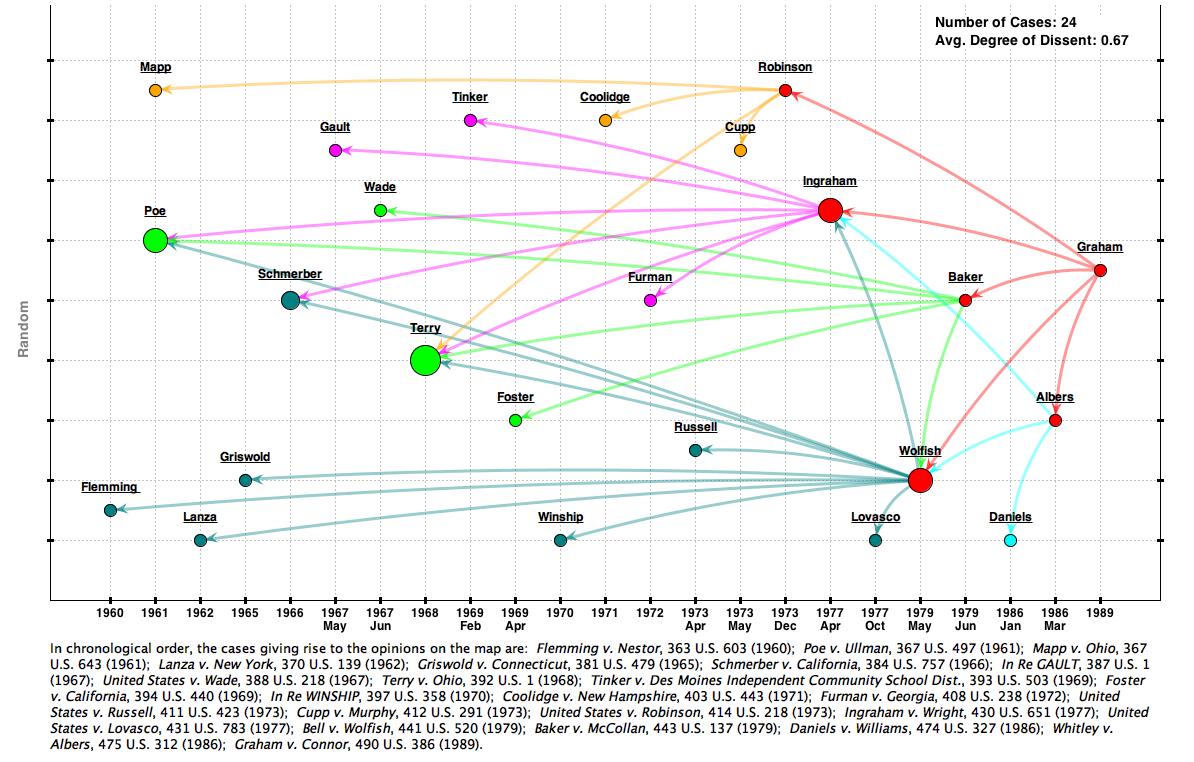

The map above depicts the same citation network as in the first map but using a schema that leverages data from the Supreme Court Database (Spaeth). The Y-axis in this second look tracks both the votes for outcome (9-0, 8-1, etc) and the decision direction (liberal/conservative) according to Spaeth.

This rendering of the network shows that all three of the initial anti-abortion speech cases — Madsen, Schenck, and Hill — had “liberal” results. On Spaeth’s coding, “liberal” decisions in this area are ones that upheld laws restricting anti-abortion speech. On the other hand, McCullen itself is coded as “conservative” because it struck down the law restricting anti-abortion speech.

I deliberately employed scare quotes in the paragraph above because Spaeth’s coding decisions are sometimes controversial — and often decisions coded as “liberal” or “conservative” do not fit with conventional understandings of those words. In this case, however, the Spaeth codes do align with conventional understanding. This is confirmed by HLP‘s classification as a “conservative” decision. In that case, as noted above, the material-support-for-foreign-terrorist-organizations survived strict scrutiny. As the map shows, that decision was a 6-3. All the conservative members of the Court joined the majority opinion, as did Justice Stevens.

In the end, analysis of this network reveals that First Amendment doctrine does not easily break down into “conservative” or “liberal” camps. Questions about content-basis and tiers of scrutiny are answered differently by justices who — in popular imagination at least — were viewed as coming from the same ideological camp. Readers interested in diving deeper into this interesting little corner of First Amendment theory should interact directly with the network on CourtListener. There you can tweak the looks, access to the full text of all the opinions, and examine the relevant Spaeth data. While you’re there, consider making your own new network!

Mapping Mistakes (of Law)

Last week, we launched our new online SCOTUS mapping tool and noted that we had also created collection of citation networks for every case decided in the Court’s 2014 Term. Today’s post introduce this network collection by examining just one of its networks.

The collection renders networks for each of the 2014 Term cases coded by the Supreme Court Database (Spaeth). Last term, there were 71 such cases. The first was Heien v. North Carolina, in which the Court held that a police officer’s reasonable mistake of law gives rise to reasonable suspicion that justifies a traffic stop under the Fourth Amendment.

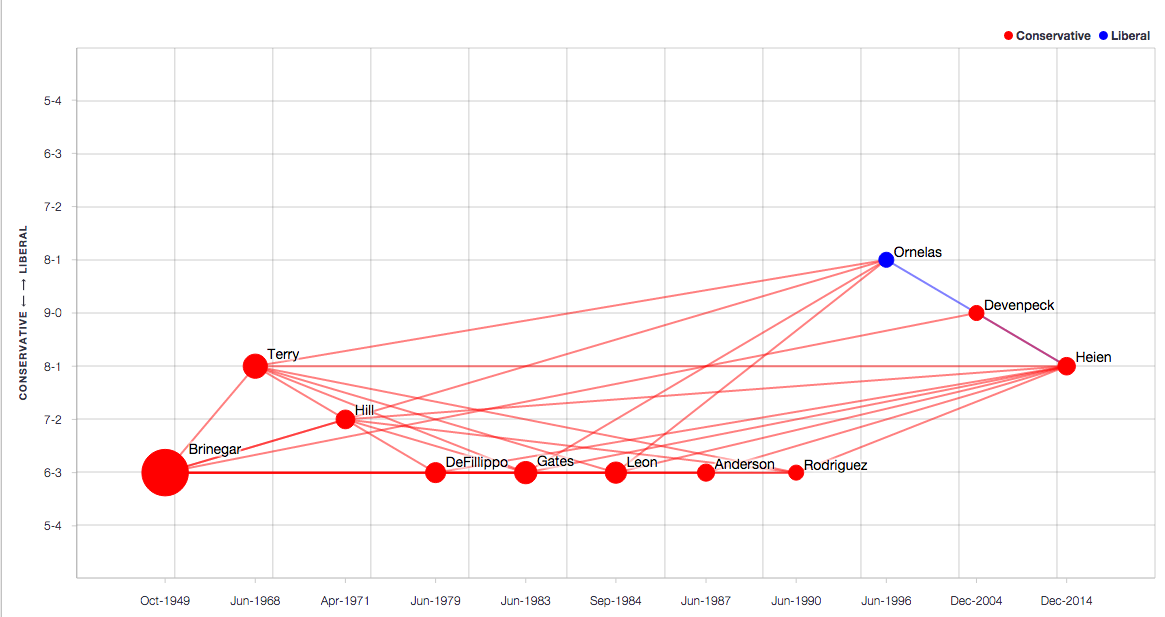

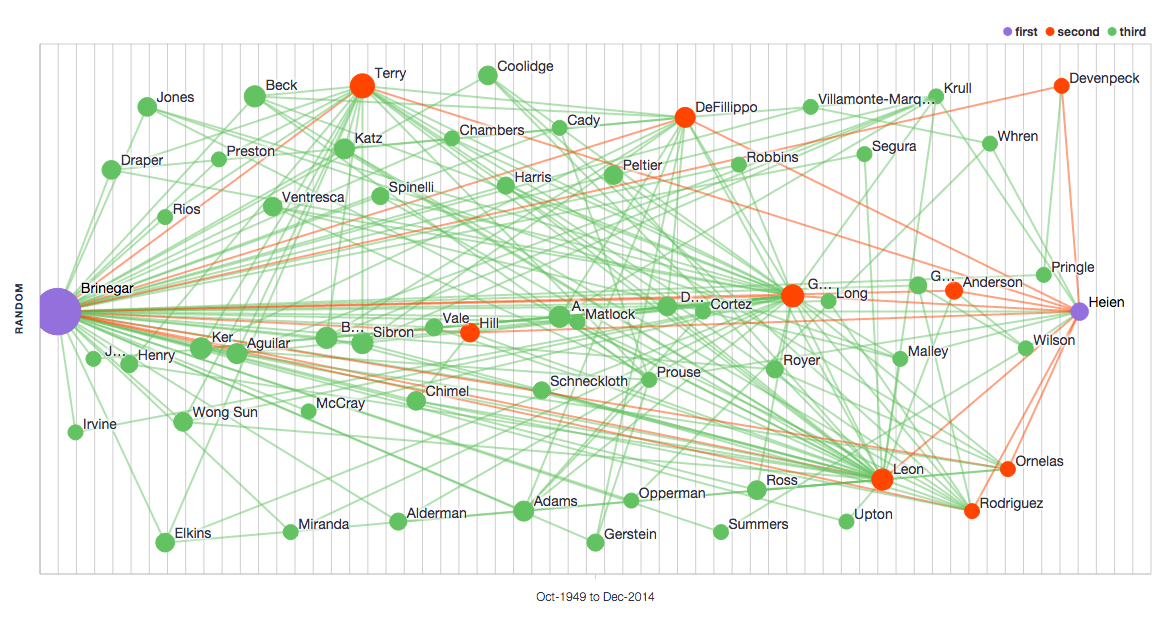

The map above shows both the citation network linking Heien back to a 1949 case called Brinegar v. United States and the Spaeth vote count and decision direction for each cases in the network.

Like every case in the collection, the choice of anchors (in this case Heien and Brinegar) is justified in the “Description” field of the network. Quite obviously, Heien serves as the “latest case” anchor because it is the case we are examining. Brinegar was chosen as the “early case” anchor this network based on textual analysis of Heien. Specifically, Brinegar is cited this way in Heien:

To be reasonable is not to be perfect, and so the Fourth Amendment allows for some mistakes on the part of government officials, giving them “fair leeway for enforcing the law in the community’s protection.” Brinegar v. United States, 338 U. S. 160, 176 (1949).

Note that the map above shows the two-degree network. This means that all the cases Heien cites that in turn cite Brinegar are shown. Since all the cases shown in the map above were cited by Heien and themselves cited Brinegar, one would expect the network as a whole to be largely concerned with mistake-of-law doctrine.

Although the two-degree network is most likely to contain relevant cases, the tool also generates a three-degree network. This would include cases citing Brinegar that are cited that Heien cites. The three-degree network is visualized this way:

While the two-degree network has only 11 cases (purple + red), the three-degree network has 61 cases (purple + red + green). This three-degree network will likely mostly include other Fourth Amendment cases; far fewer of them will be mistake-of-law cases.

Hopefully, this quick treatment gives interested folks an idea of what is contained in the 2014 Term collection. To review: Every 2014 Term case is linked to an earlier case to create a network. The choice of early anchor is specifically justified by analysis of the text of the 2014 Term case. Two- and three-degree networks are created and can be viewed by reference to the Spaeth data. Of course, links to the complete text of every opinion are also provided.

Next time: Quantitative analysis of SCOTUS citation networks.

New Online Mapping Tool Launches Today!

After months of hard work, we here at In Progress are proud to announce the launch of a new online Supreme Court doctrinal mapping tool. A collaboration between the SCOTUS Mapping Project at the University of Baltimore and Free Law Project, the tool enables anyone to create doctrinal maps similar to those that have been featured on this blog for the past year and a half. Use of the website is 100% free and the entire project is open-source.

Folks interested in checking out the tool can go here. We’ve also put together plenty of resources to help lawyers, law students, professors, and others interested in learning more about this innovative form of legal research. Resources include:

- A revamped Libguides library of maps that now features embedded networks created with the tool.

- A blog post that explains the basic features of the tool via a timely analysis of Justice Scalia’s 4th amendment jurisprudence.

- A collection of citation networks for every case decided in the Court’s 2014 Term. The collection offers an in-depth example of the potential of doctrinal mapping.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll examine maps created with the tool and explore what they can teach us about Supreme Court doctrine. For now, however, we’ll just pop the champagne and celebrate the launch!

Conference Alert: Fate of Legal Scholarship March 31-April 1, 2016

Citations Can Be Pretty

Baltimore these days gets dark early. Most of the trees have no leaves. Rather than get depressed, In Progress counsels color. Enjoy a pretty citation network! (Click image to open full-sized version).

And if you like your pictures moving, enjoy this GIF of the same network growing node by node…

To download a full size version of the gif as a quicktime movie, click HERE.

Want to know what these maps mean? Next time!