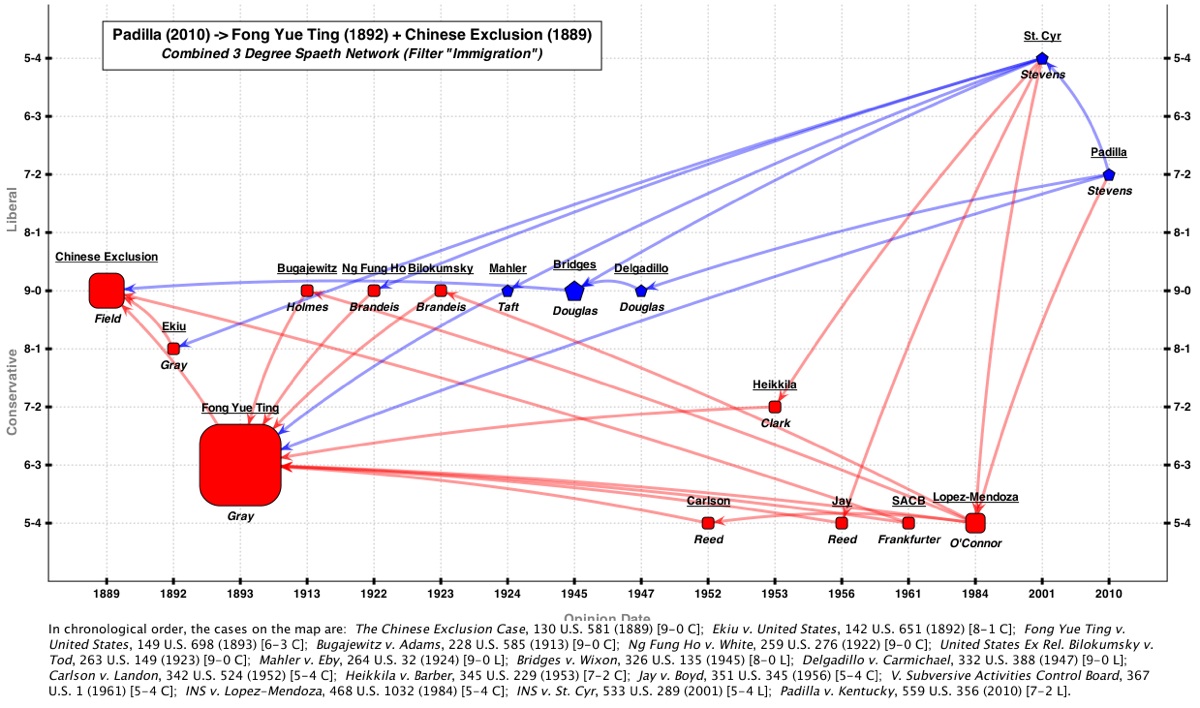

This week I’ve been working on improving a map of immigration doctrine. I created the original map by combining 3-degree citation networks connecting Padilla v. Kentucky (2010) to Fong Yue Ting (1893) and the Chinese Exclusion Cases (1889). In my last post, I updated the original map to include the “outcome votes” and “outcome directions” for the pre-1946 cases. I attempted to code these cases in a manner consistent with the Spaeth dataset, which does not include pre-1946 cases. Today, I begin the process of converting the map from a Spaeth visualization to a map that more effectively represents the competing traditions in immigration doctrine. These competing traditions form the basis of a doctrinal dialectic.

The first step in this process is to identify and display the authors of the majority opinions represented. This is an important step because it confronts and lays bare a bedrock fiction in Supreme Court discourse — the fiction that “the Court” issues opinions rather than individual justices. When referring to prior opinions, the standard convention is to say “the Court held this” or “the Court stated that.” Yet opinions all have authors. Knowing the identity of these authors becomes important when we seek to locate competing traditions in doctrine. Here is the same Spaeth map from last time with authors included (click on the map to see in full size).

Adding authors adds value. We see, for example, that Justice Stevens wrote both modern “liberal” opinions (Padilla and St. Cyr) while Justices Field and Gray wrote the foundational “conservative” opinions (Chinese Exclusion and Fong Yue Ting). We also see that the titans Holmes, Brandeis, Taft, and Douglas wrote the string of unanimous opinions from 1913 to 1947. The idea that this doctrine evolved as a long-running conversation among these justices becomes easier to swallow with the actual opinion authors displayed.

Yet the map needs work. Right now, it only shows half of the doctrinal story. The missing half concerns dissents. Dissenting opinions can exert massive influence over the development of Court doctrine even if they do not formally state “the law.” Thus, I believe that no truly careful study of any given are of Court jurisprudence can ignore dissents. Introducing dissents into the picture is thus the next step in the development of this map. Stay tuned!