All nine Justices of the Supreme Court voted the same way in last Term’s much-anticipated Confrontation Clause decision, Ohio v. Clark. All agreed that the admission at trial of an out-of-court statement made by a 3 year-old to his teacher identifying his abuser did not violate the Sixth Amendment rights of the accused. However unanimous the vote for outcome, the Clark court was deeply divided on the justification for this result. Indeed, Clark stands as latest salvo in longstanding doctrinal war over the meaning of the Confrontation Clause and the reach of the Crawford line of cases. In this post, I map out the lineage of this bitter war’s competing sides.

To understand the battle lines, recall first that Crawford was decided in 2004 and it overruled a 1980 case called Ohio v. Roberts. Justice Scalia wrote Crawford and he has jealously guarded Crawford‘s doctrinal development ever since. Justice Alito, a former prosecutor, wrote the majority opinion in Clark. In his separate Clark concurrence, Scalia pointedly rejects Alito’s reasoning:

The opinion asserts that future defendants, and future Confrontation Clause majorities, must provide “evidence that the adoption of the Confrontation Clause was understood to require the exclusion of evidence that was regularly admitted in criminal cases at the time of the founding.” This dictum gets the burden precisely backwards—which is of course precisely the idea. Defendants may invoke their Confrontation Clause rights once they have established that the state seeks to introduce testimonial evidence against them in a criminal case without unavailability of the witness and a previous opportunity to cross-examine. The burden is upon the prosecutor who seeks to introduce evidence over this bar to prove a long-established practice of introducing specific kinds of evidence, such as dying declarations [] for which cross-examination was not typically necessary.

Revealingly, Scalia then continues:

A suspicious mind (or even one that is merely not naïve) might regard this distortion as the first step in an attempt to smuggle longstanding hearsay exceptions back into the Confrontation Clause—in other words, an attempt to return to Ohio v. Roberts. But the good news is that there are evidently not the votes to return to that halcyon era for prosecutors; and that dicta, even calculated dicta, are nothing but dicta. They are enough, however, combined with the peculiar phenomenon of a Supreme Court opinion’s aggressive hostility to precedent that it purports to be applying, to prevent my joining the writing for the Court.

Here Scalia transparently accuses Alito the prosecutor of trying to subvert Crawford and reinstate the deposed rule of Ohio v. Roberts. And Scalia is quite right to make this accusation.

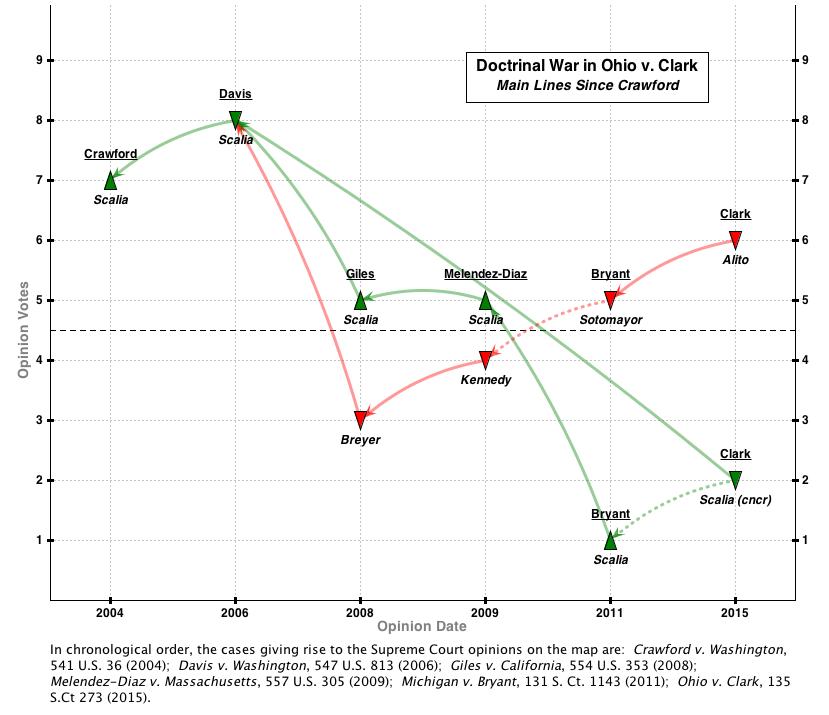

As I’ve previously written, Crawford doctrine has had its bashers since at least 2008’s Giles v. California. Although the Crawford-bashing school remained in dissent in Giles and 2009’s Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts, the insurgency captured a majority in 2011’s Michigan v. Bryant (over Scalia’s dissent) and now again in Clark. This basic story is visualized in Map 1 below (click on map — and all maps in this post — to open full-sized image with links to opinions in Casetext).

In Map 1, the “Scalia line” asserting a robust Confrontation Clause vision is pictured in green while the “bashing line” is in red. Arrows pointing up indicate opinions where the author concluded the Sixth Amendment was violated, whereas downward-pointing arrows represent arrows where the author concluded no violation occurred. The number of votes any opinion received is represented by its position on the Y axis.

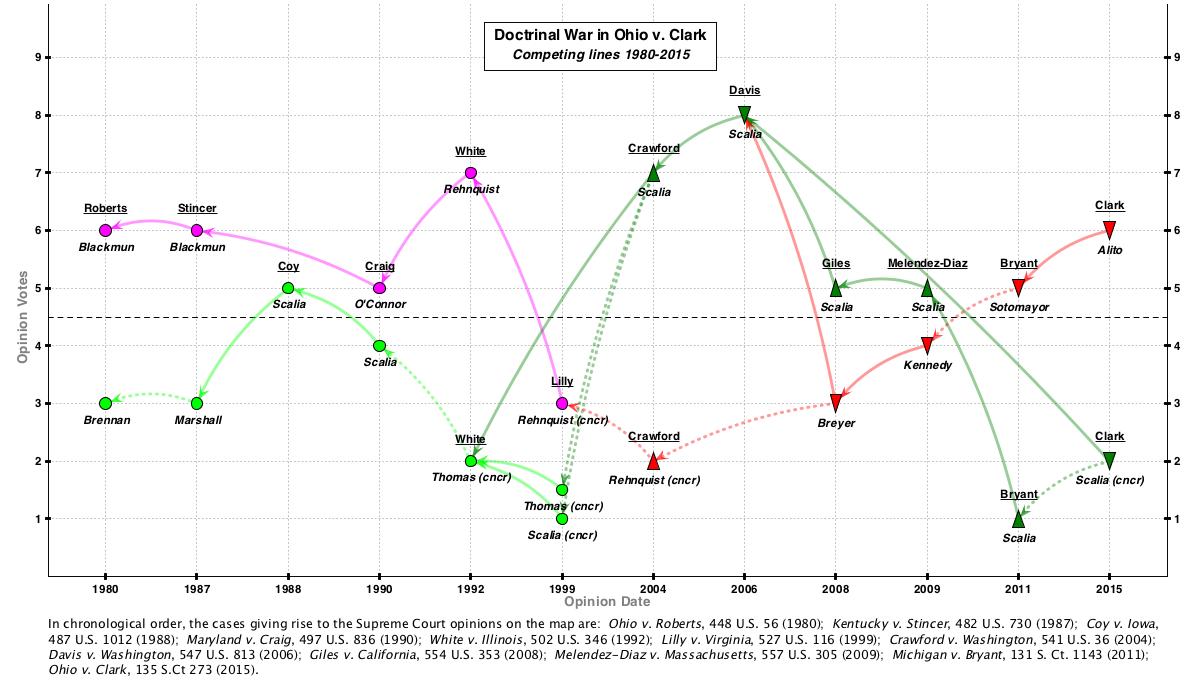

While Map 1 presents a simplified picture of the main competing lines since Crawford, it would be wholly inaccurate to suggest that Crawford marks the beginning of the doctrinal war. As mentioned, Crawford overruled Roberts and the overruling campaign took over two decades to succeed. Map 2 provides a glimpse at the longer dialectic.

In Map 2, we see Crawford‘s ancestral line pictured in lime green while the deposed Ohio v. Roberts line is represented in magenta. Dotted lines connecting opinions on the map indicate implied connections rather than direct citations. The map suggests a continuity between Alito’s majority opinion in Clark and Justice Blackmun’s majority opinion in Roberts 35 years ago.

Crawford‘s ancestry is fascinating. Scalia was not yet on the Court when Roberts was decided in 1980. He had joined by the time Kentucky v. Stincer was decided in 1987. Interestingly, Scalia joined the majority in that case (opinion again written by Blackmun). Justice Marshall dissented in Stincer and was joined by Brennan and Stevens. Then Scalia apparently had a change of heart. In 1988’s Coy v. Iowa, Scalia wrote the majority opinion. He was joined by Brennan, White, Marshall, Stevens. The old guard dissented — O’Connor wrote with Blackmun and Rehnquist joining. Remarkably, Scalia cited Marshall’s Stincer dissent in his majority opinion. This signaled the beginning of a beautiful relationship. From then on, Scalia, Brennan, Marshall, and Stevens became best of friends in the Confrontation Clause arena.

Consider Maryland v. Craig, decided in 1990. Those four strange bedfellows (Scalia, Brennan, Marshall, and Stevens) all dissented. Scalia writing for his new gang. And the doctrinal war was on in earnest. The old guard saw O’Connor pen the majority opinion joined by her comrades Rehnquist, White, Blackmun and Kennedy. The plot thickened even more in 1992’s White v. Illinois. At this juncture, the old guard still retained control. Though Chief Justice Rehnquist authored the White majority opinion, newcomer and upstart Clarence Thomas issued a prescient separate concurrence. Thomas presented an originalist theory of the Confrontation Clause and Justice Scalia joined him.

Change was in the air. By the time Lilly v. Virginia was decided in 1999, the Court was fractured. The lead opinion was written by Justice Stevens and only got four votes. More importantly, Justice Rehnquist’s concurrence only garnered O’Connor and Kennedy’s votes. Scalia and Thomas both separately concurred proclaiming their allegiance to the vision set down in Thomas’ White concurrence. Then the revolution happened in Crawford. Chief Justice Rehnquist wrote separately to say that he disapproved of overruling Roberts. Though O’Connor joined him, the old guard was clearly deposed. Blackmun and White had left. Kennedy had waffled. And so a new era was ushered in.

Now, of course, the pendulum may be swinging back towards the old era. Scalia is clearly worried in Clark that Alito is trying to reinstate the deposed Ohio v. Roberts line to the doctrinal throne. Only Ginsburg is solidly aligned with Scalia at the moment. Only time will tell if Alito’s campaign will win the necessary votes.

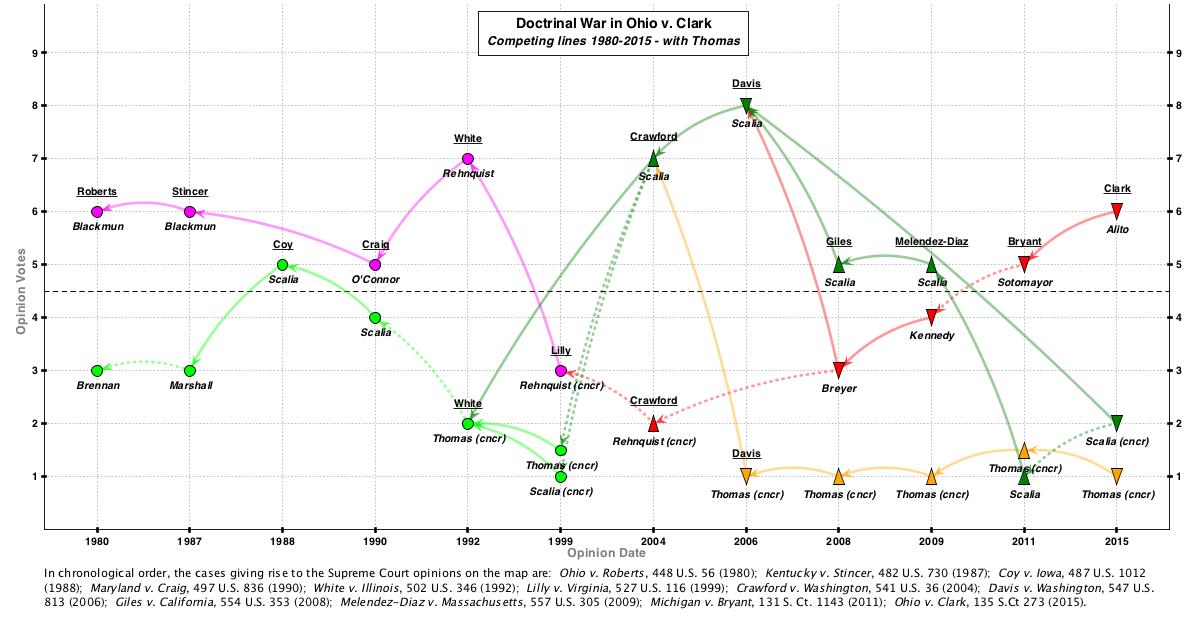

Readers interested in taking a deeper dive can to explore the opinions in detail. Hopefully, the maps can help readers navigate the complex doctrine while Casetext can provide a way for folks to annotate and muse about meaning. Before signing off, however, I want to present one final map. It is Map 3 below.

Map 3 is the same as Map 2 except that it adds in Justice Thomas’ post-Crawford opinions. Although many might find Thomas’ solo efforts quixotic, I have previously suggested that he has often played the swing-vote role in this area. Moreover, as shown above, Thomas’ concurrence in White exerted a an important influence on the doctrine’s development. Love him or hate him, the man deserves some props. And sometimes it is the quietly consistent voices that can take command of a doctrine and shape its destiny.

I appreciate this valuable info.