Does precedent determine how the Supreme Court will rule in any given case? Not necessarily. While past decisions should guide the Court’s resolution of new problems, justices may disagree on the scope of prior rulings. Justices may even disagree on whether undeniably on-point precedent should be overruled. Caselaw thus provides partial context for case resolution, but not the whole picture. Nonetheless, the precedent picture always matters. Today, I look at picture in Spokeo v. Robins, the standing case argued this past Tuesday.

In Spokeo, the question is whether respondent Thomas Robins has standing to sue petitioner Spokeo, Inc — an online “people search” company — for Spokeo’s alleged violation of the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCA). The basic story is that Spokeo published false information about Robins on the Internet. The standing problem arises because this false information really didn’t harm Robins in a concrete way. Oversimplifying, the question is whether such a minor violation of the FCA alone creates a cognizable “injury” for Article III purposes.

Here’s where precedent comes in.

Robins argues in his brief that the only way that the Court could fdeny him standing is if it overrules two prior cases — Havens Realty Corp v. Coleman and Public Citizen v. Department of Justice. Decided in 1980s, both Havens and Public Citizen involved “statutory standing” for violations of the Fair Housing Act (Havens) and the Federal Advisory Committee Act (Public Citizen). Robins asserts that these precedents essentially determine the outcome here. For more modern support, Robins points to the Court’s 2007 decision Massachusetts v. EPA as consistent with his interpretation of the doctrine.

Spokeo naturally disagrees. In its brief, Spokeo argues that the Court’s precedents demand a very concrete showing of “injury in fact.” According to Spokeo, this baseline Article III requirement is typified by cases like Warth v. Seldin and Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife. Furthermore, Spokeo accuses Robins of seeking the kind of speculative standing most recently rejected in the Court’s 2013 Clapper v. Amnesty International decision.

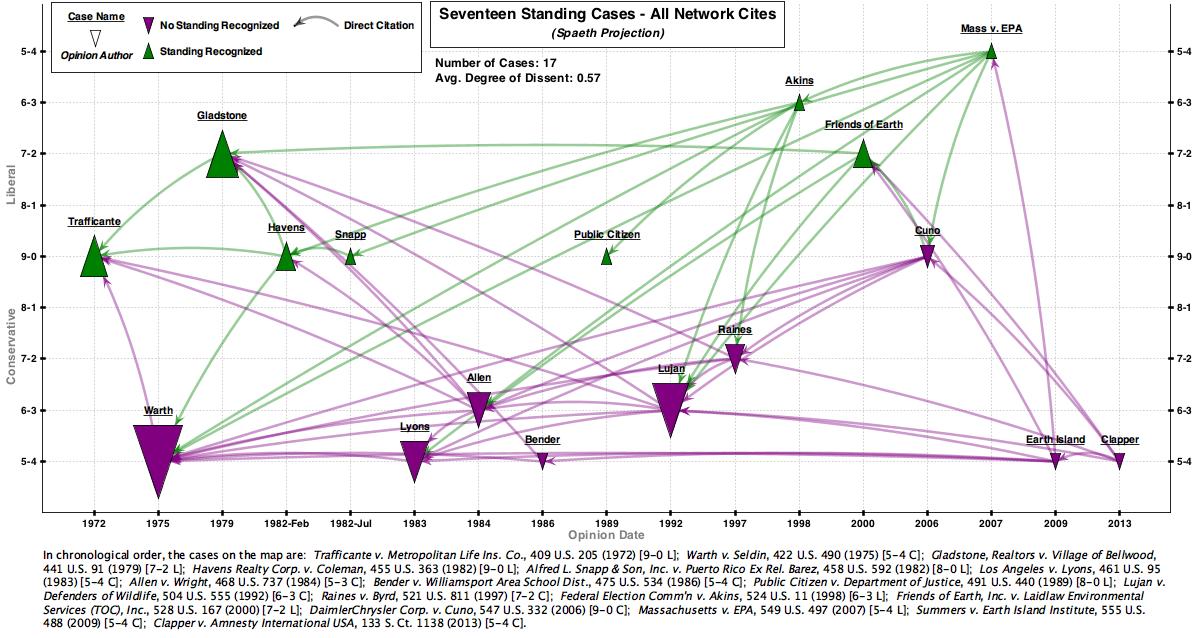

It perhaps goes without saying that both parties — and the various amici weighing in — cite a whole lot of standing precedent in their briefs. Is it realistic to think that any justice (or clerk) will review all the cases cited before arriving at a final decision or justifying their conclusion in an opinion? I doubt it. So what are the most important cases that the justices will look to? Consider seventeen prime candidates (click image for full-sized map).

Map 1 shows the citation network connecting seventeen standing cases that play major roles in the Spokeo briefing. This map uses a Spaeth Projection; cases are linked to the Supreme Court Database. Note that green upward-facing triangles represent cases where the Court found standing. By contrast, the Court rejected standing in those cases represented by purple downward-facing triangles. Unsurprisingly, Robins relies most heavily on green cases (including Havens, Public Citizen, and Mass v. EPA) while Spokeo places its eggs in the purple basket (with cases like Warth, Lujan, and Clapper).

Two points about this first map deserve emphasis. First, the triangles grow in size the more a case is cited by other cases in the network. Thus, the map shows that the two most relied-upon “no standing” cases are Lujan and Warth while the two most relied-upon “yes standing” cases are Gladstone and Tafficante. So if you want to get up to speed on the contours of the debate, try reading these cases first. Second, the map shows the Court has recently divided sharply over standing. The last three cases that came down the pike — Mass v. EPA, Earth Institute, and Clapper — were all 5-4s. In other words, it comes as no surprise that reports on the Spokeo argument indicate that we are probably in for another squeaker.

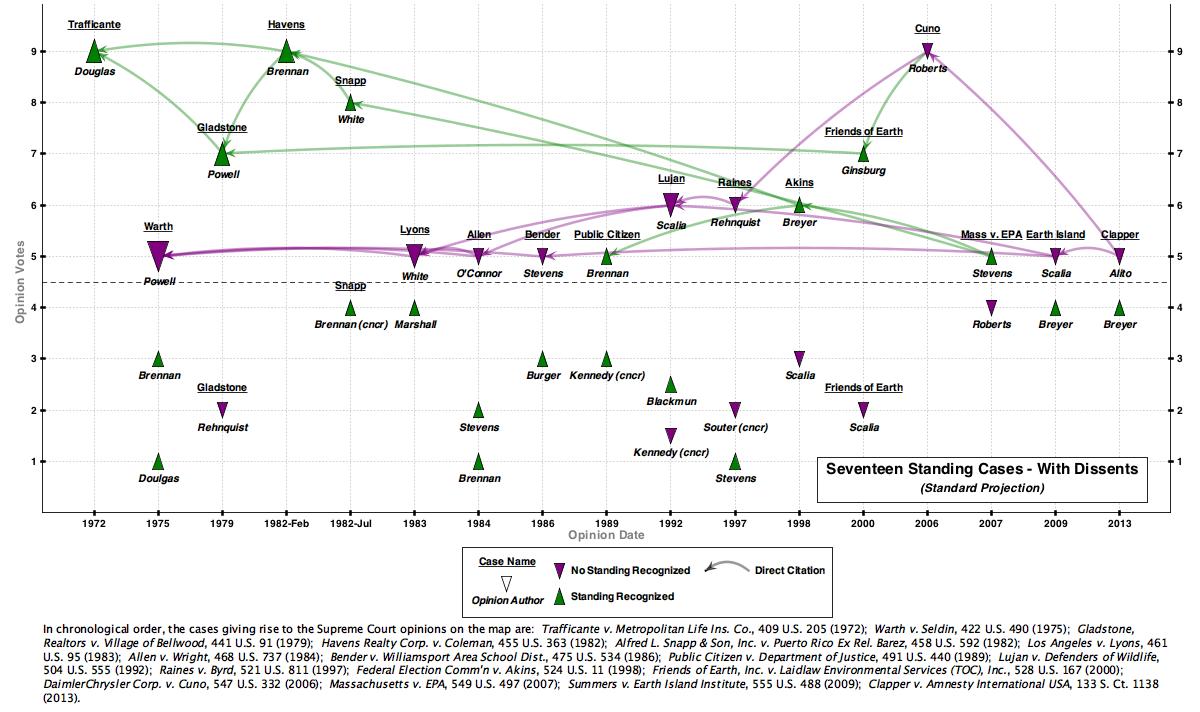

Let’s now visualize these same seventeen cases in a different way.

Map 2 focuses on “opinions” rather than “cases.” Links on this map are to opinion text on Casetext. Note that this uses what I call a “Standard Projection” — the Y-axis represents the number of votes a particular case opinion received. Therefore, all the opinions pictured below the dashed line across the middle of the map are dissents or concurrences. For ease of reference, names of the specific opinion authors appear below the triangle representing that opinion.

This second map presents a clearer picture of the ongoing constitutional conversation. It makes apparent that the traditionally more “liberal” justices are inclined to find standing where the more “conservative” one aren’t. Thus, the highly controversial majority opinion in Lyons, which found no standing for a victim of police chokeholds seeking prospective injunctive relief, was written by Justice Scalia. In dissent, Justice Marshall cried foul. More recently, Justice Scalia took a narrow view of standing in the Earth Island Institute case while Justice Breyer wrote the lead dissent.

So do the maps predict the resolution of Spokeo? Alas, no. As I stated at the top of this post, case outcomes are not determined by precedent alone. And key policy considerations will inevitably come into play in Spokeo since it has such broad implications about responsibility for inaccurate information on the Internet. With that said, I can’t help but notice that the best cases for Robins — those cases in green — are mostly older and mostly written by folks no longer on the Court. In my book, that doesn’t bode well for the respondent. Going on the picture of precedent alone, I’d predict a purple “no standing” outcome and victory for Spokeo.

It’s hard to come by experienced people in this particular topic,but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks