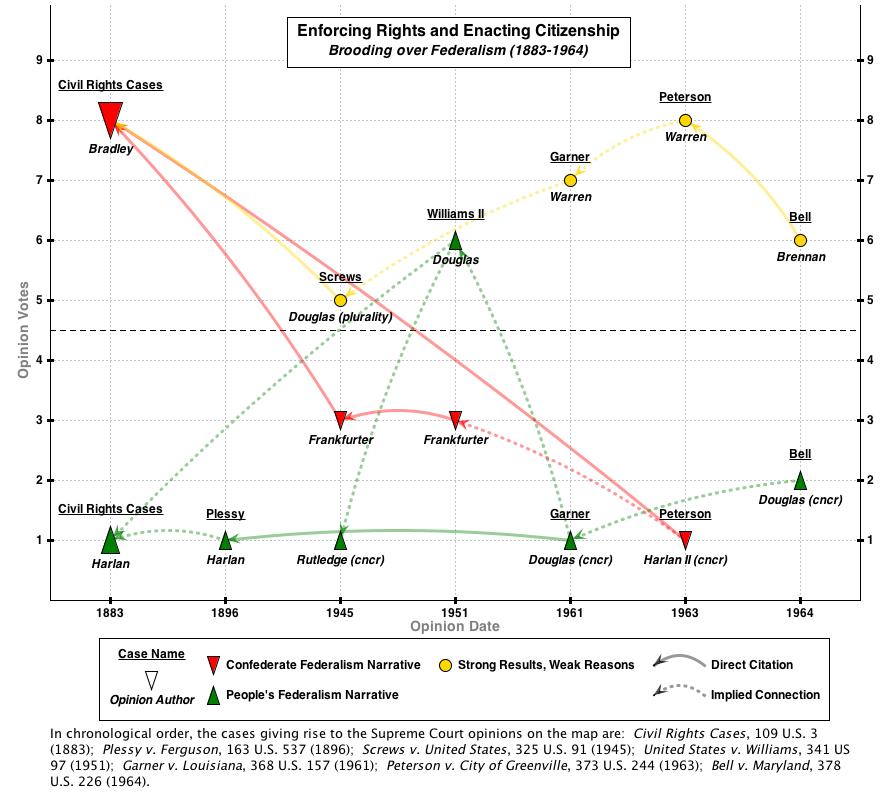

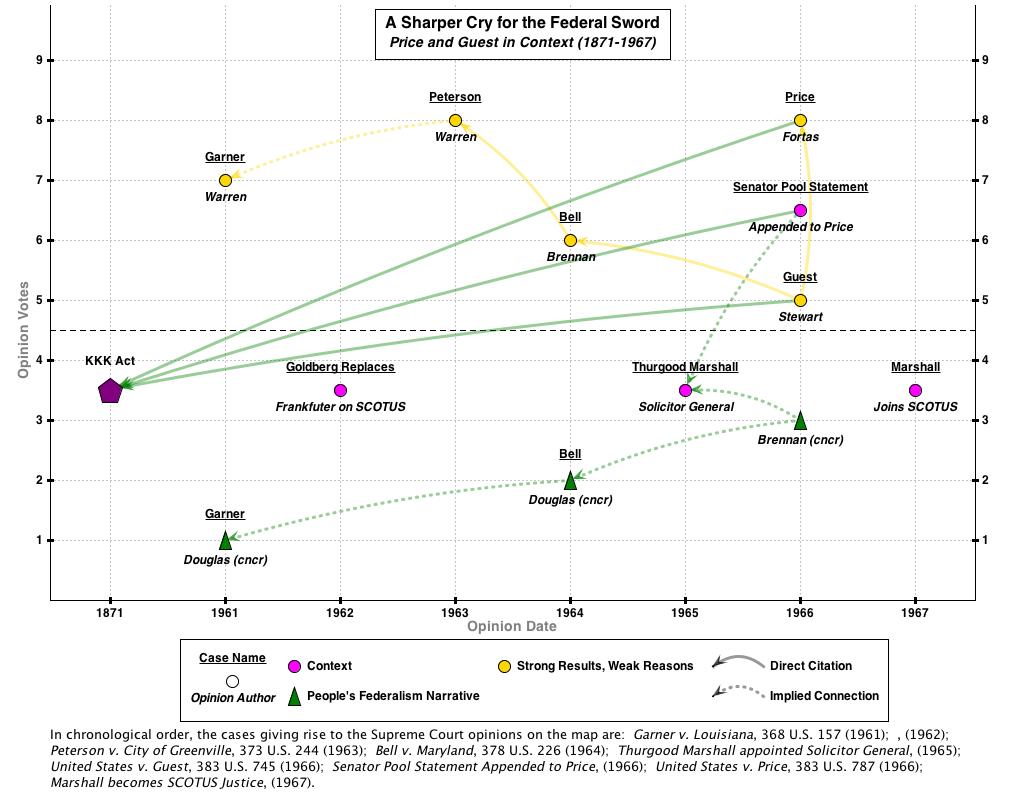

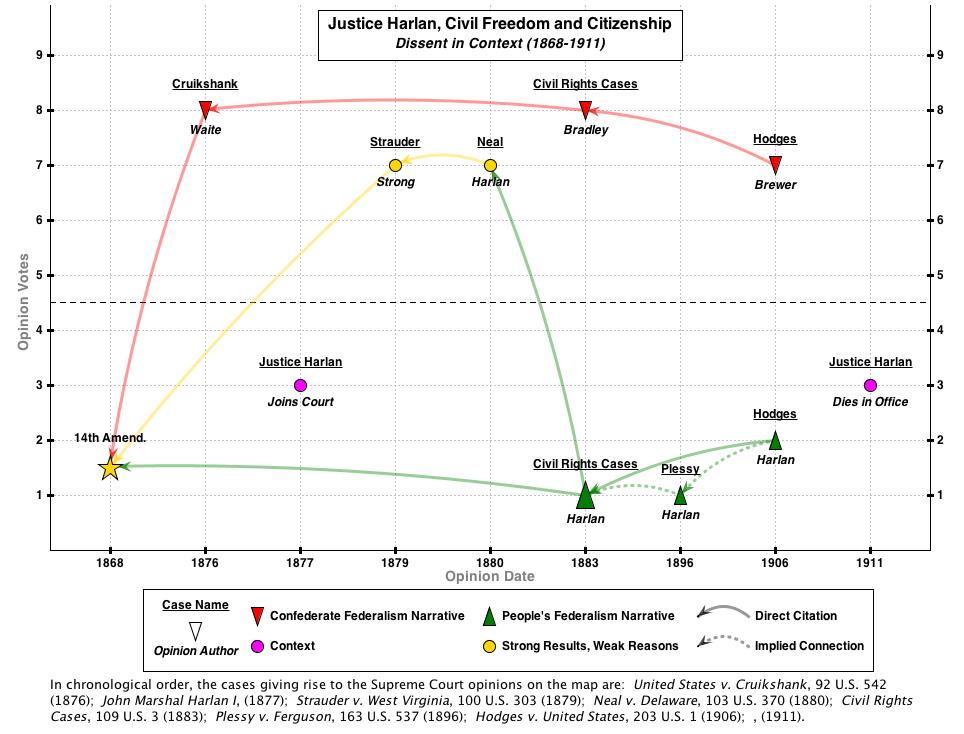

It’s time to wrap up and conclude this blog series on “Beyond the Confederate Narrative.” For context, recall the article’s argument as described in prior posts. The Confederate narrative started out as a state-power justification for slavery and then transformed into a Reconstruction-defeating jurisprudence (Part 1 ; Part 2), This narrative was influential yet always contested.Justice Harlan’s Civil Rights Cases dissent articulated a contrary “People’s narrative” (Part 3) and this doctrinal tradition helped shape the debate in key 1950s-60s era civil rights cases (Part 4). Today, this final Part will proceed by identifying the ghosts of the Confederate narrative that remain in Court’s civil rights and federalism doctrine. We conclude with a call for a doctrinal exorcism.

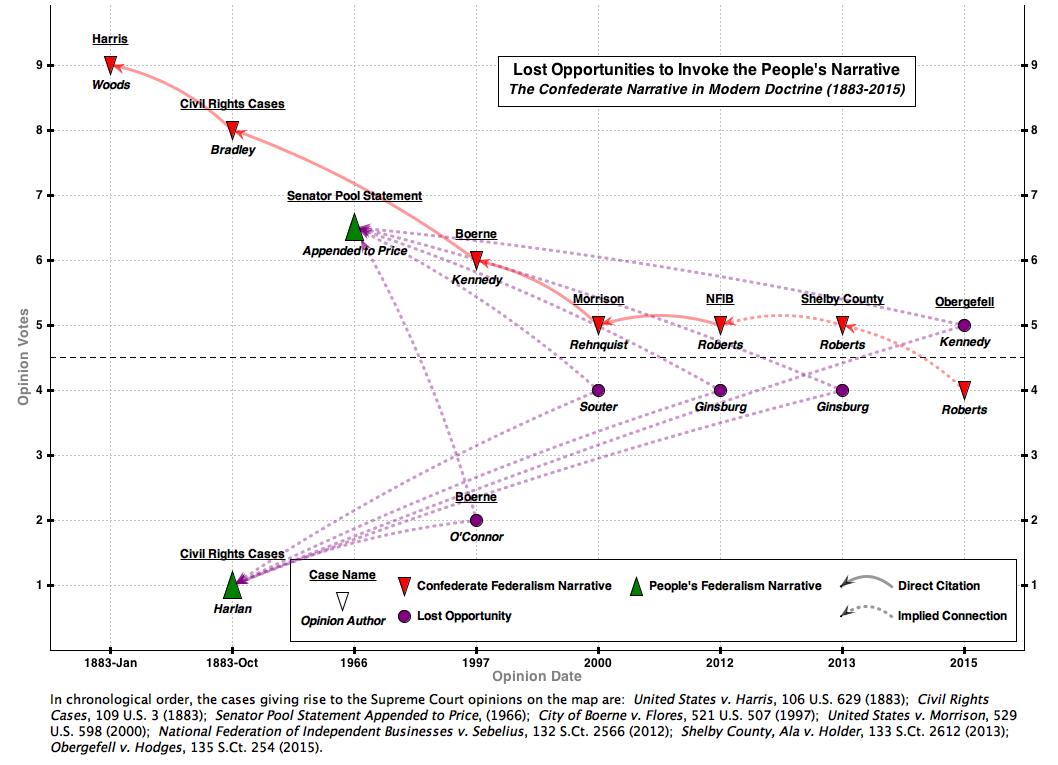

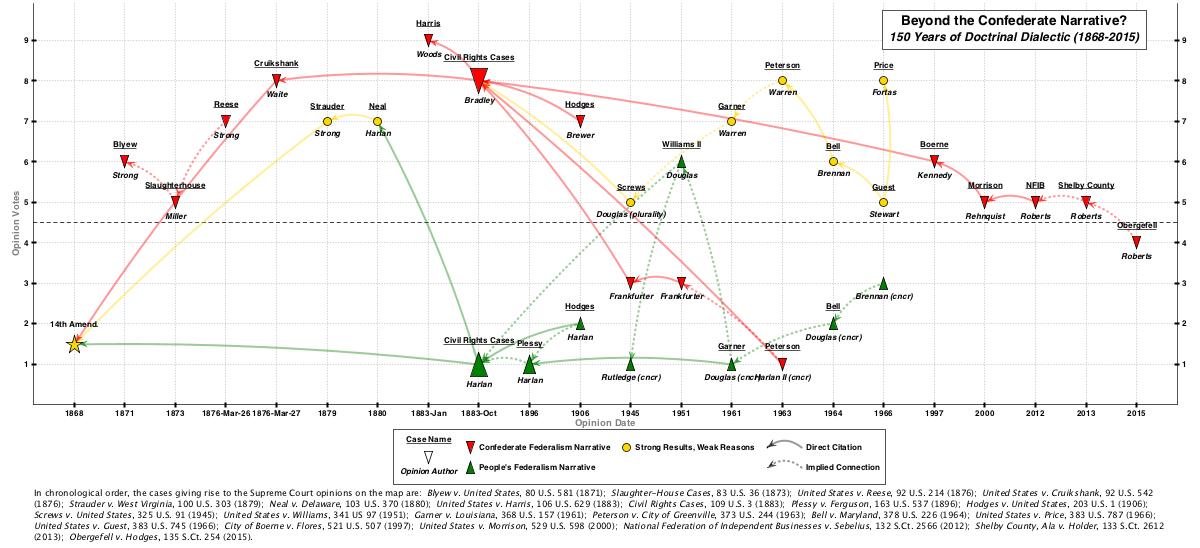

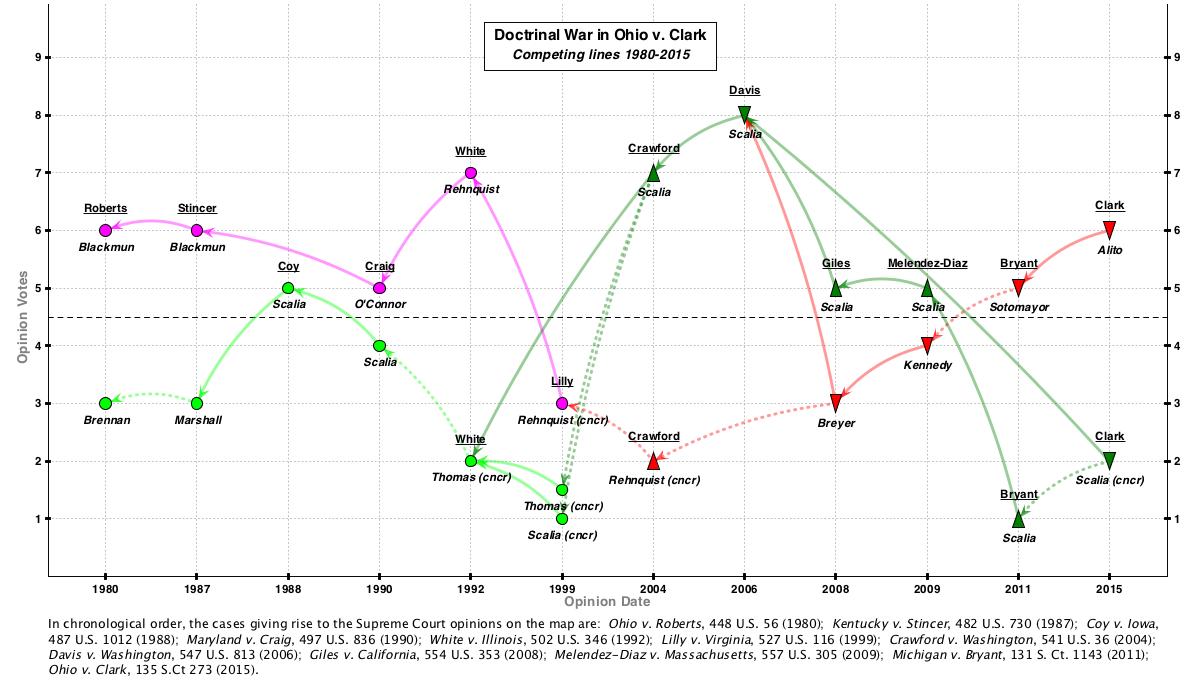

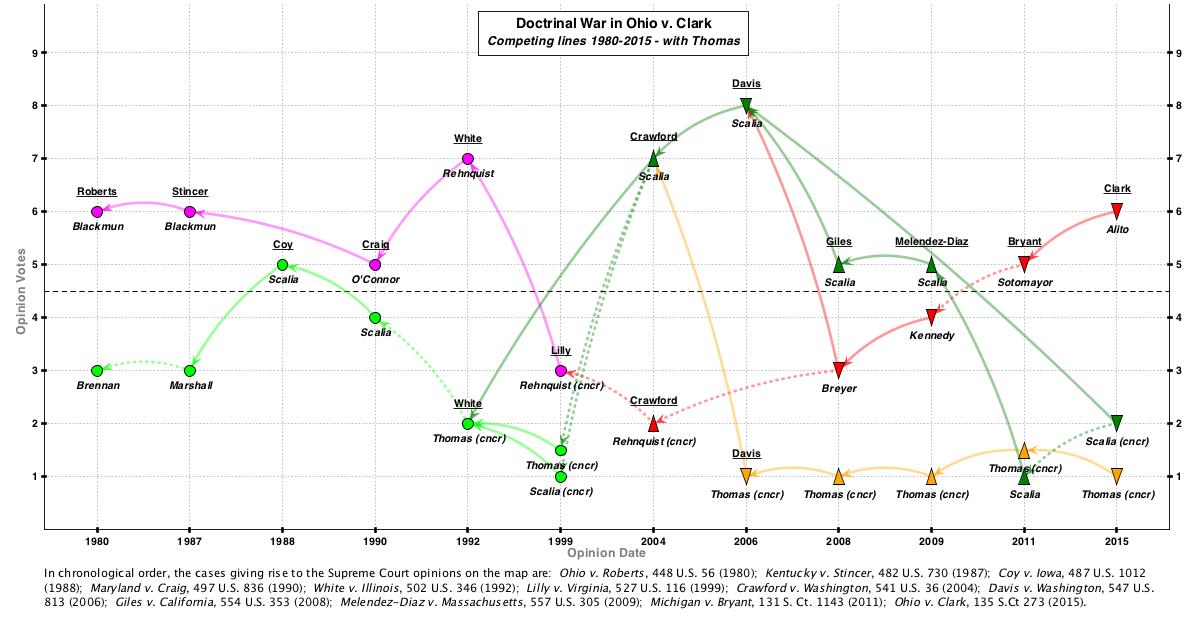

The map above sketches out our basic argument regarding modern doctrine. (As usual, click the map for full-sized image with links to underlying cases). Four contemporary Court majority decisions — City of Boerne (1997), Morrison (2000), NFIB (2012), and Shelby County (2013) — directly descend from cases like Harris (1883) and the Civil Rights Cases (1883). In addition, Chief Justice Roberts’ dissent in Obergefell (2015) also falls within this tradition. All these opinions embrace a Confederate narrative by articulating a contestable understanding of the Constitution. These opinions all embrace the proposition that the States’ sovereign power severely limits the federal power to protect civil rights under the Reconstruction Amendments.

This map presents a deliberately limited sketch rather than an exhaustive survey. It shows a loose network of conceptually related cases all advancing a consistent perspective on federalism, civil rights, and the meaning of of Reconstruction. Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion in City of Boerne typifies this perspective. His opinion undertook a highly questionable reading of the 14th Amendment’s ratification history to justify the conclusion that the Enforcement Clause is remedial rather than substantive.

In Morrison, Chief Justice Rehnquist elaborates on this perspective. His majority opinion explicitly cites Harris and the Civil Rights Cases as justification for limiting Congressional power to prevent violence against women. Rehnquist considered this interpretation necessary “to prevent the Fourteenth Amendment from obliterating the Framers’ carefully crafted balance of power between the States and the National Government.”

Finally, Chief Justice Roberts’ opinions in NFIB v. Sebelius, Shelby County, and Obergefell incarnate the latest expression of this narrative. Collectively, Roberts’ opinions advocate an ideal of “equal sovereignty” for States. This ideal effectively deprives the federal government of power under the Reconstruction Amendments. The power deprived is the to enforce human rights like the rights to vote, marry or receive health care.

Of course, we recognize that not all on the Court agreed with the opinions we criticize in City of Boerne, Morrison, NFIB, Shelby County, and Obergefell. Yet we lament the contrary opinions in those cases as lost opportunities. This is because these opinions tragically failed to invoke the People’s narrative. Though on the right side of history (in our view), these competing opinions missed the opportunity to explain how and why the Reconstruction Amendments actually expanded the federal government’s constitutional power to enforce human rights. They failed to invoke Justice Harlan’s Civil Rights Cases dissent or Senator Pool’s defense of the 1870 Force Act, for example.

Yet Harlan’s dissent and Pool’s defense should be invoked.Those treasure troves of analysis should not sit idle in the pages of the US Reports; they beg for re-reading and exposition. Ultimately then, the bottom line of our argument is that a true understanding of human rights and dignity require us to rediscover lost treasures such as these and reclaim the People’s perspective on Reconstruction and its Amendments.

Readers interested in the fine details of this argument can read our entire article. Meanwhile, our genealogical project is ongoing and we would love to engage with scholars and activists keen on such conversation. Together perhaps we can reawaken the People’s narrative from its doctrinal slumber and move beyond the Confederate narrative.