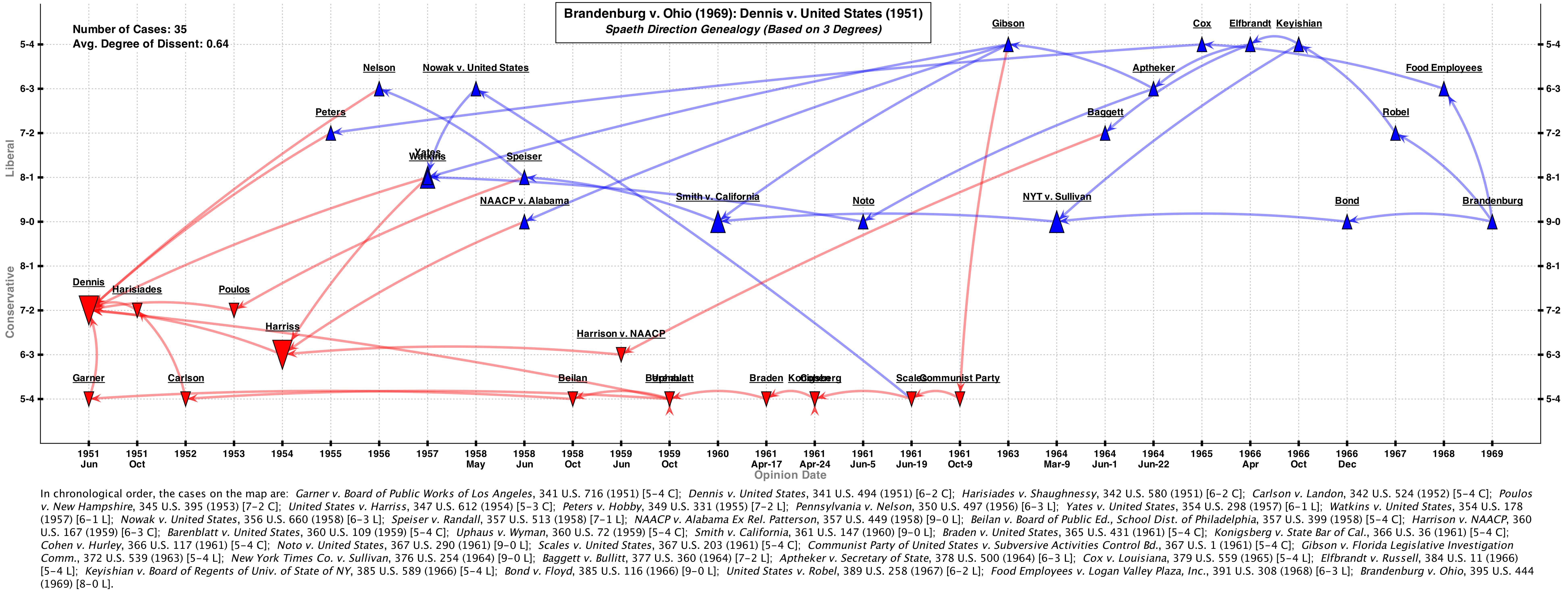

This semester I’m teaching First Amendment law for the very first time and it’s proving to be a wonderful experience. First Amendment cases have great stories behind them and the Supreme Court’s doctrine is complex and highly contested. To navigate this complexity, I’ve found doctrinal mapping enormously useful for my own learning. Yet I’ve also realized that automatically generated citation networks need editing. Today I want to discuss this editing process.

The example I’ll use is the Court’s “commercial speech” doctrine, which generally concerns acceptable versus unacceptable restrictions on advertising. The section on commercial speech spans 27 pages of our class textbook — the excellent (imho) Sullivan & Feldman First Amendment volume (5th Ed. 2013) — and it discusses 23 cases. There are three principal cases (Virginia Pharmacy (1976), Central Hudson (1980), and 44 Liquormart (1996)) and 20 squibs. The latest squib is the only Roberts Court decision — Sorrell (2011). For the purposes of this analysis, I’ll call these 23 cases the Sullivan & Feldman canonical cases.

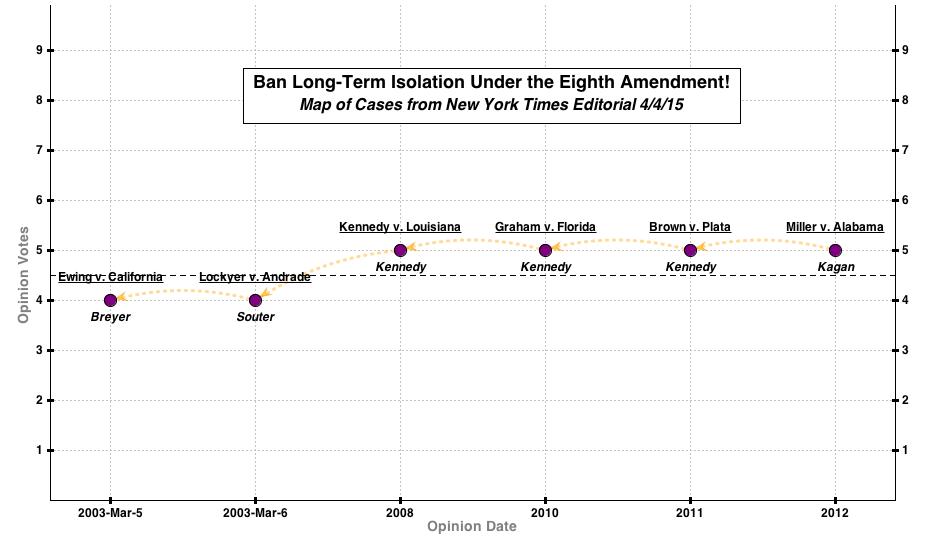

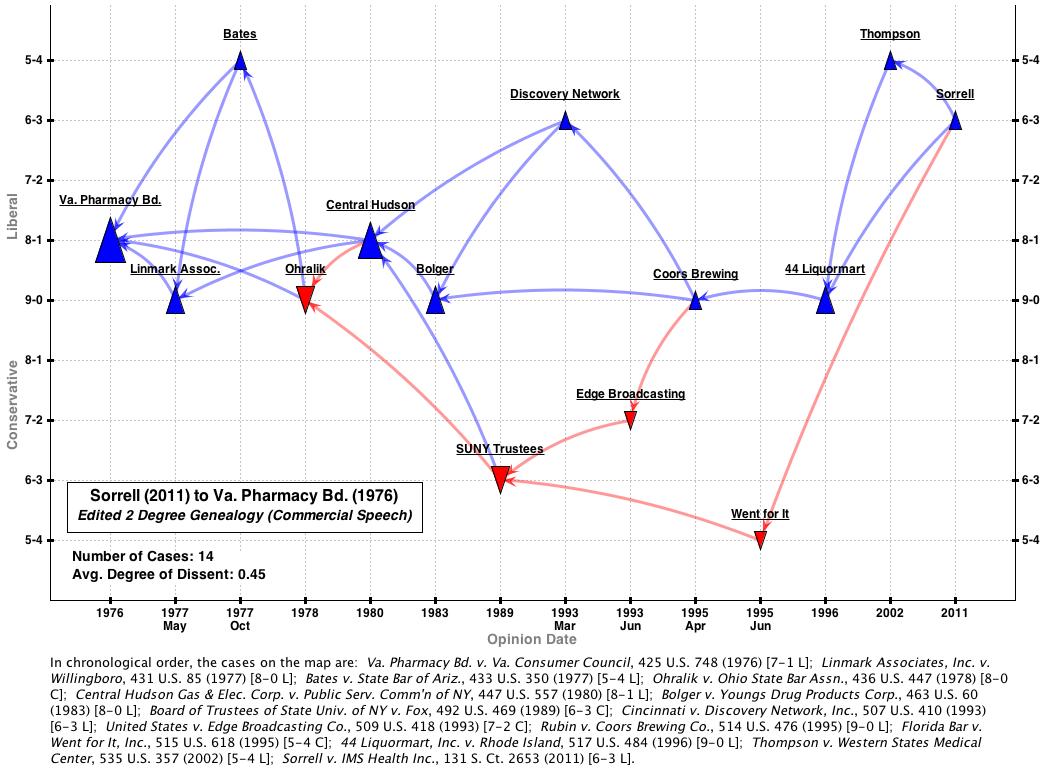

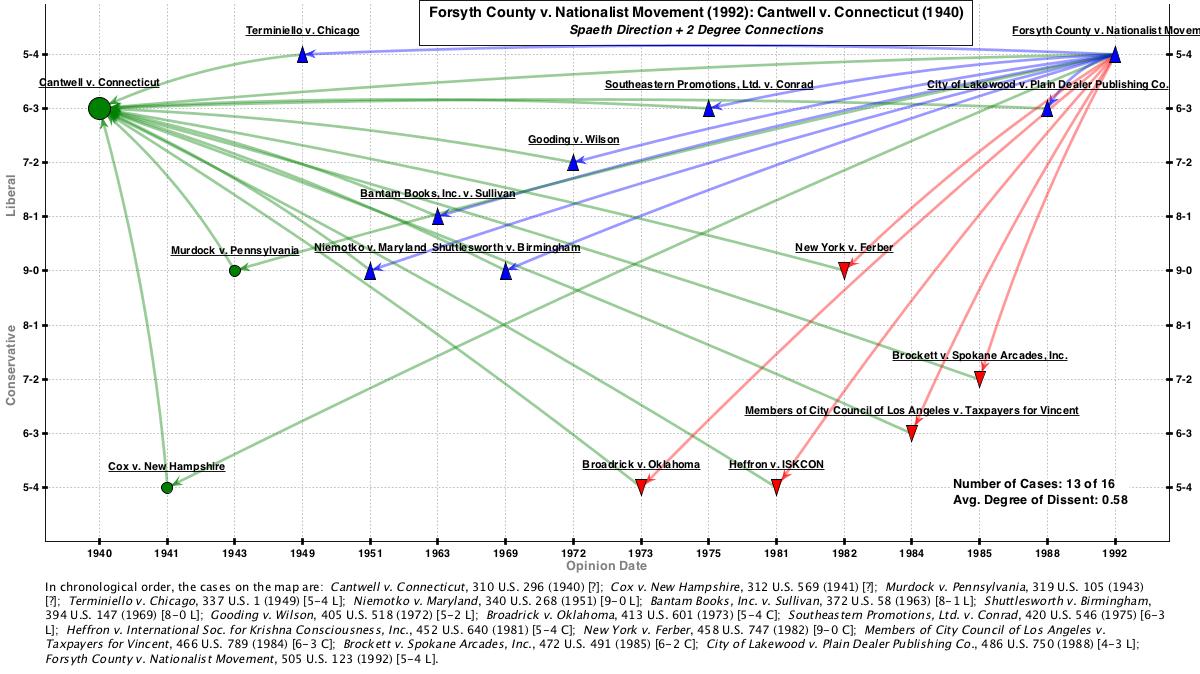

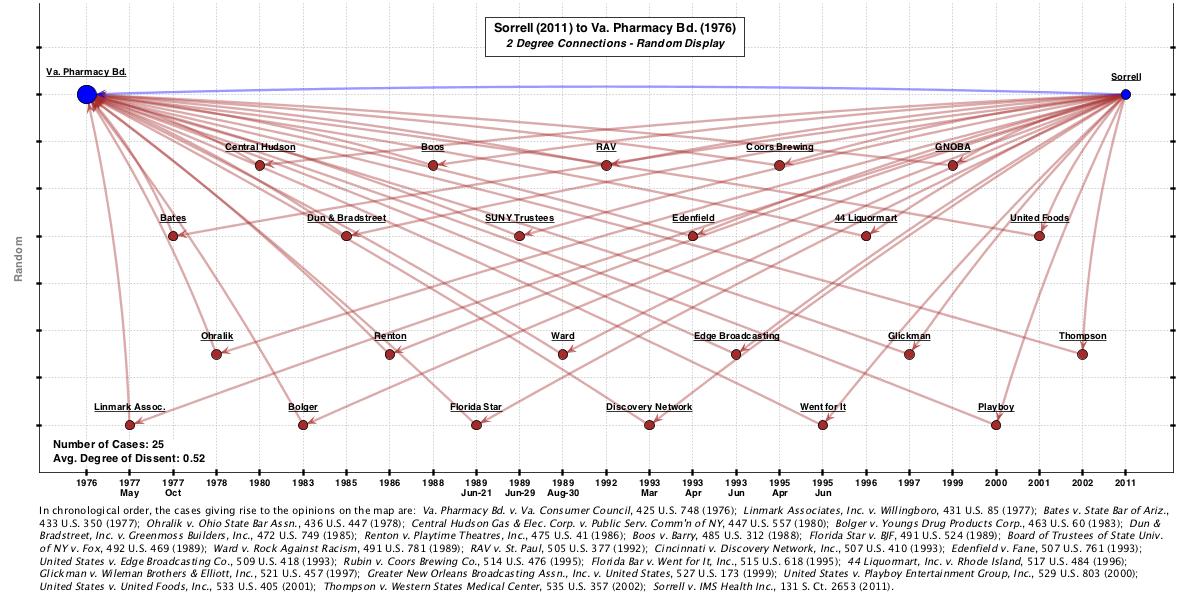

To create a machine-made competing map, I used SCOTUS Mapper to generate a 2-degree network linking Sorrell to Virginia Pharmacy. The program’s algorithm pulls into the network all the cases that Sorrell cites that in turn cite Virginia Pharmacy. This is what that network looks like (as with all the images in this post, click for full-size map).

Now this 2-degree network is actually quite rich. It contains 25 cases — including all three of the Sullivan & Feldman principal cases as well as 11 of the 20 squibs. While the 2-degree network thus picks up 14 out of the 23 canonical cases, it also picks up 11 “extra” cases not included in the canonical line.

Now this 2-degree network is actually quite rich. It contains 25 cases — including all three of the Sullivan & Feldman principal cases as well as 11 of the 20 squibs. While the 2-degree network thus picks up 14 out of the 23 canonical cases, it also picks up 11 “extra” cases not included in the canonical line.

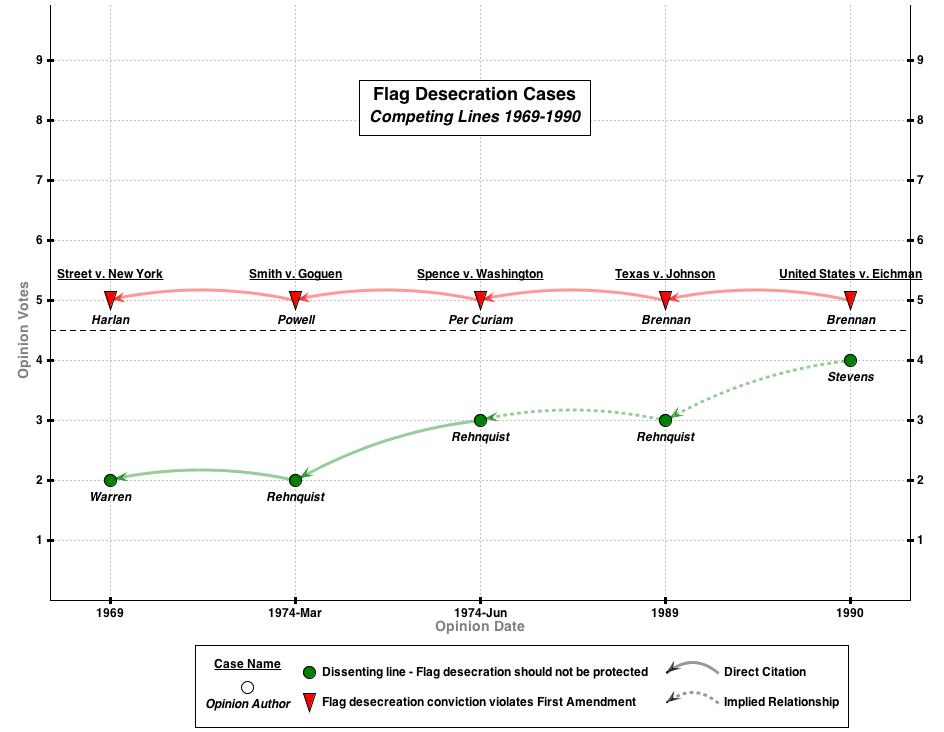

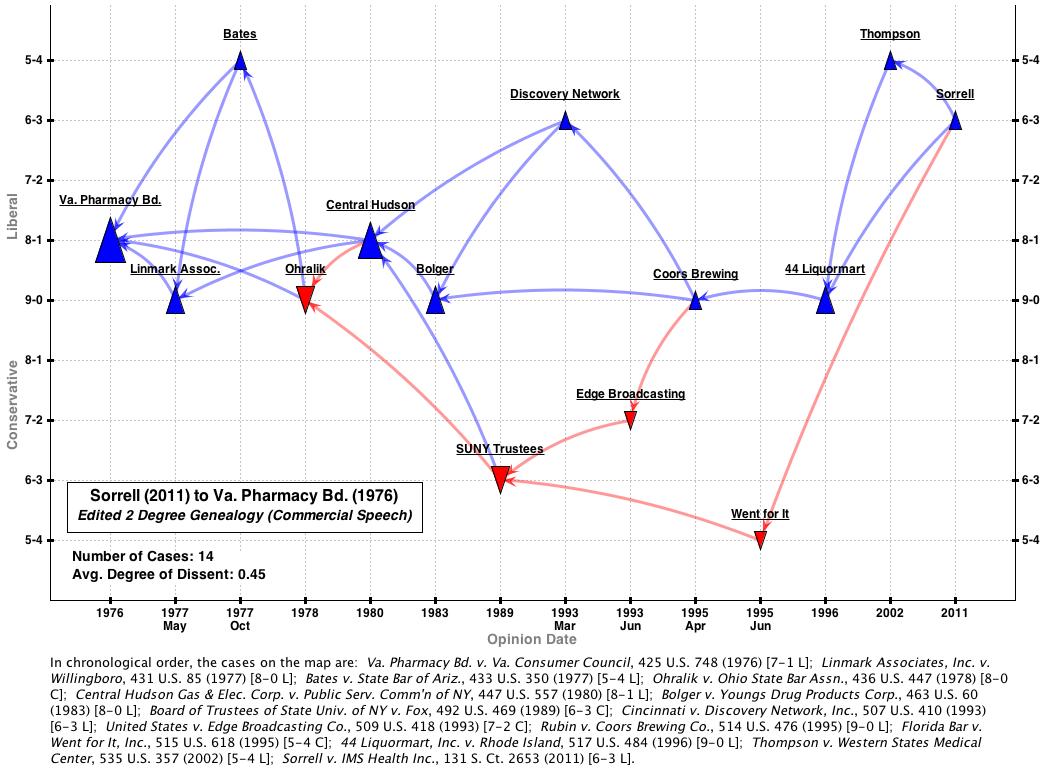

I wanted to edit out these extra cases so I ran the network through a text filter on “commercial speech.” This machine-based edit knocked out 4 cases (the remaining 21 cases all contained the phrase). From there, I had to edit out by hand the 7 cases that Sullivan & Feldman did not include in the canonical line. (Let’s call those cases “non-canonical 7” — I’ll return to them below). After that editing, I ended up with this map:

Note that this second map uses a “Spaeth projection.” The Y axis is no longer random — it represents that Supreme Court Database code for both outcome direction and judgment vote. Red cases are Spaeth-coded “conservative” — meaning the Court upheld a restriction on commercial speech. Blue cases are Spaeth-coded “liberal” — meaning the Court struck down a restriction on commercial speech.

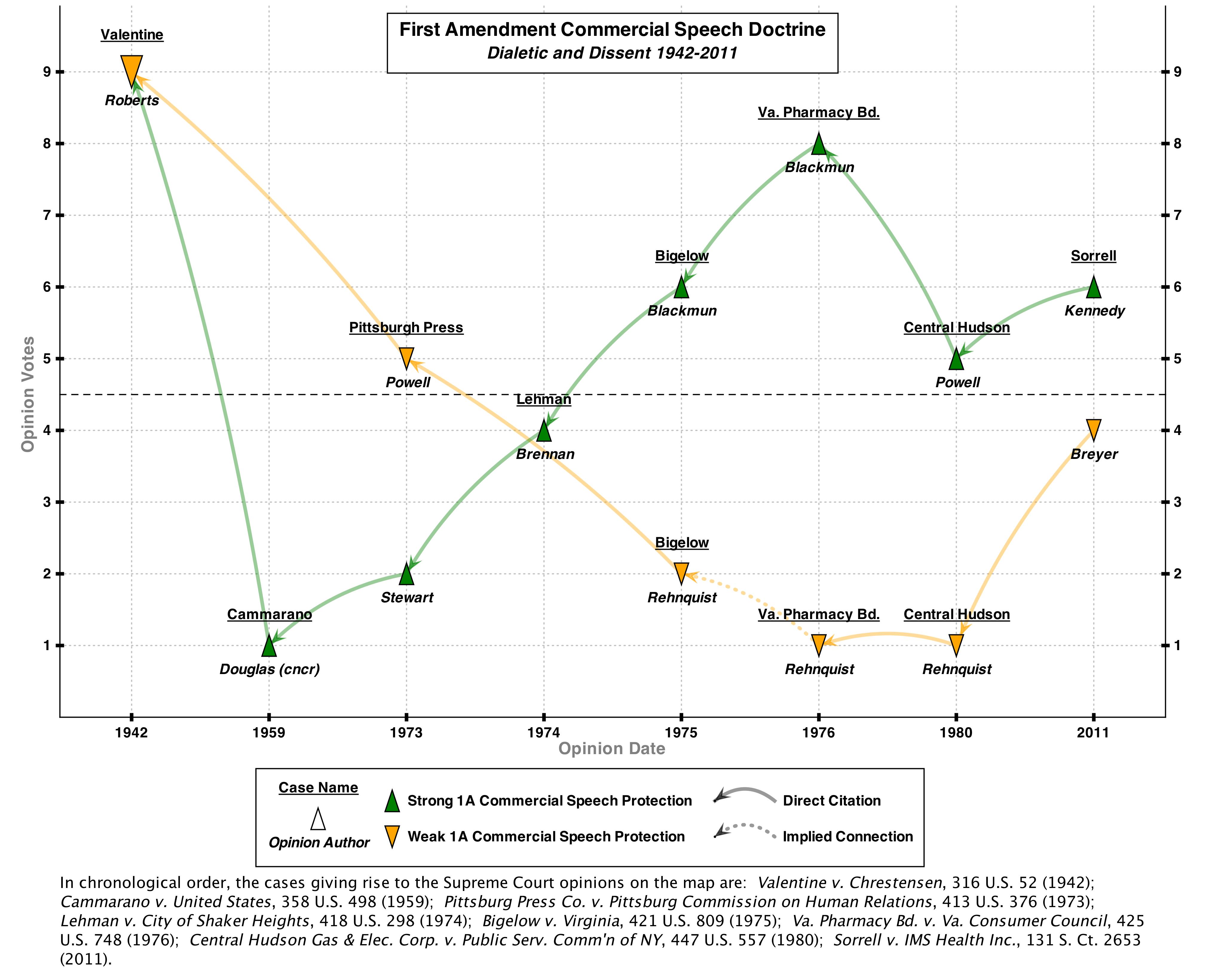

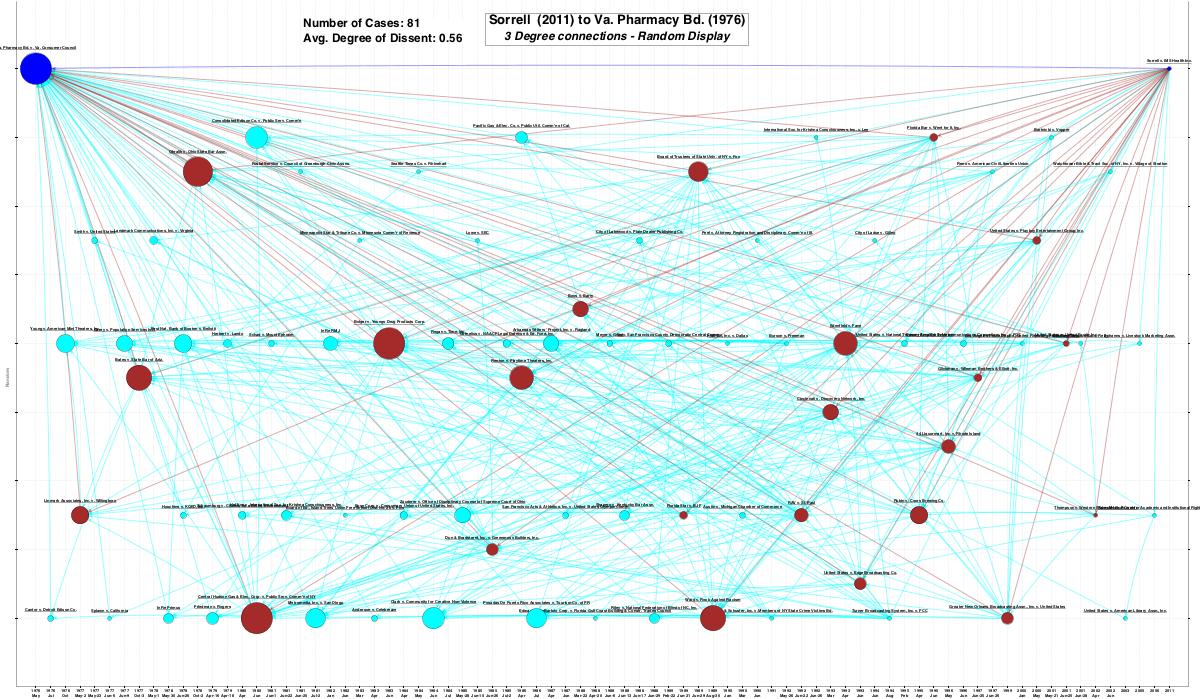

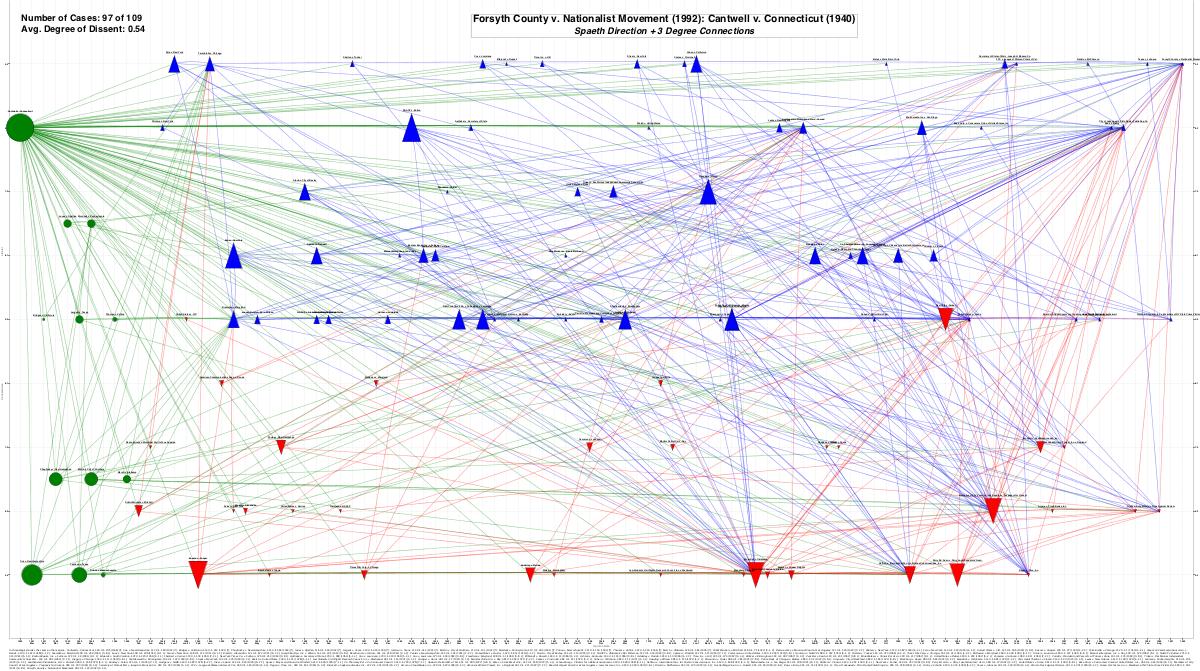

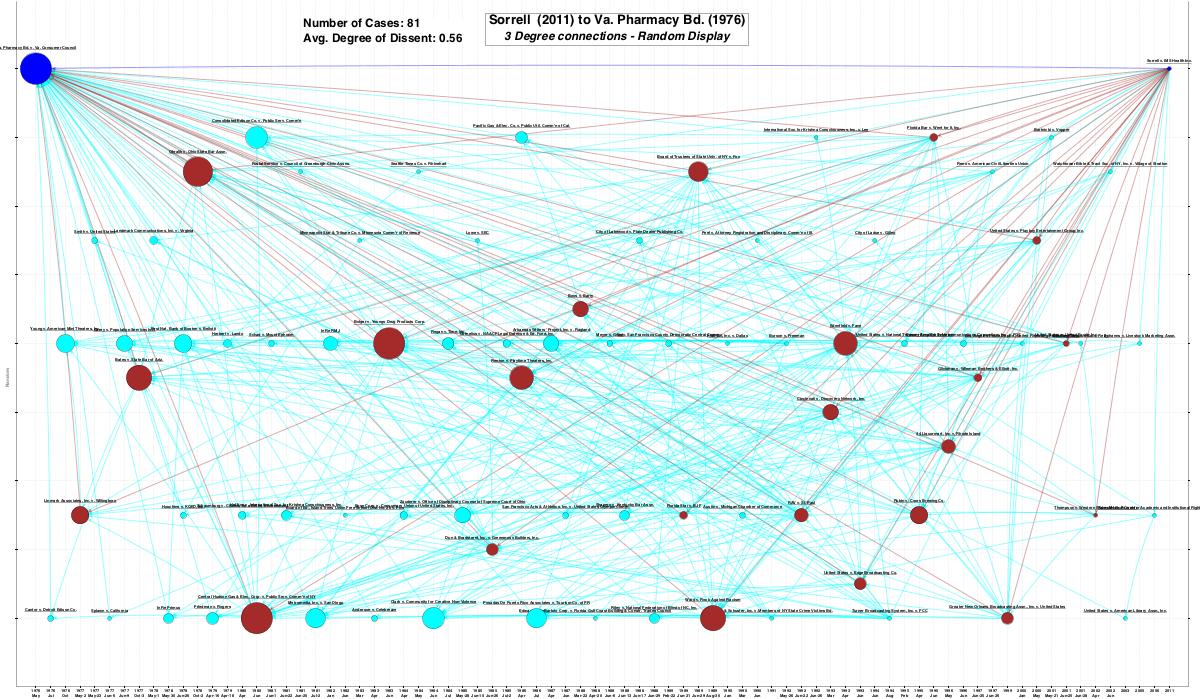

Now what does it take to automatically capture the remaining 9 squib cases from the Sullivan & Feldman canonical line? I tried generating a 3-degree network connecting Sorell to Virginia Pharmacy. So in addition to all the 2-degree cases, this network includes all the cases cited by 2-degree cases that in turn cite Virginia Pharmacy. Here’s what that network looks like on a random Y-axis projection:

Unsurprisingly, this network is very large — 81 cases. The good news is that the network easily picks up all 23 cases from the Sullivan & Feldman canonical line. The bad news is that it picks up 58 extra cases.

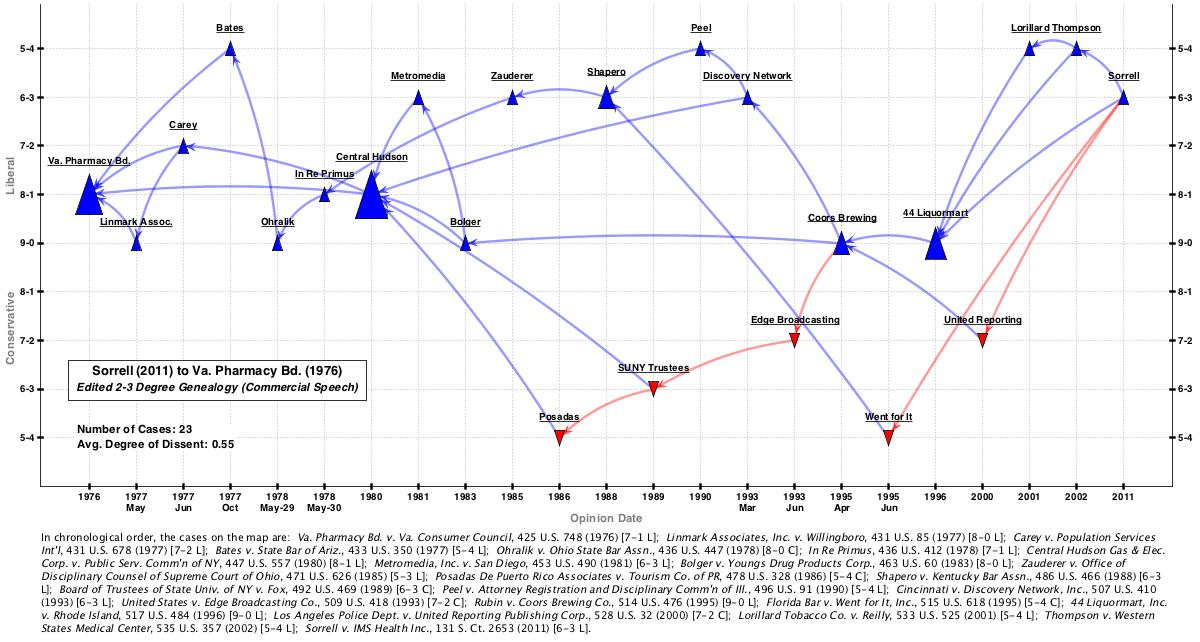

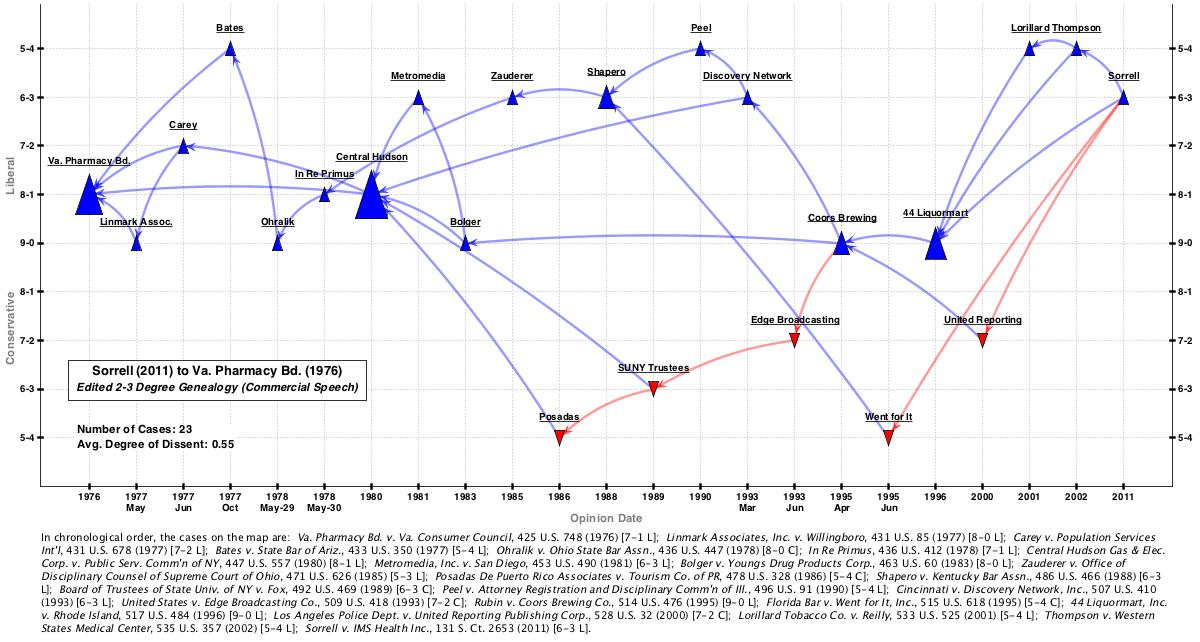

To get rid of these, I first tried the machine filter route. After automatically excluding cases without the phrase “commercial speech”, the network shrunk from 81 to 53 cases. Once again, that’s a good start but not nearly good enough. To get rid of the other 20 cases, I had to edit by hand. Upon completion of that edit, here’s what the new network looks like using a Spaeth projection:

This map represents all the Sullivan & Feldman canonical commercial speech cases. Getting those extra 9 cases in requires a healthy dose of editing of the 3-degree network.

This map represents all the Sullivan & Feldman canonical commercial speech cases. Getting those extra 9 cases in requires a healthy dose of editing of the 3-degree network.

So how important are those extra 9 cases? Are they really part of the core commercial speech line? All that we can conclude for certain is that none of the opinions in Sorrell cited those 9 cases. As far as the justices sitting in 2011 were concerned, none of those 9 cases was important in justifying their decisions. Of course, the diminished “2011 value” of the cases does not mean that “the missing 9” had no impact on the network’s development.

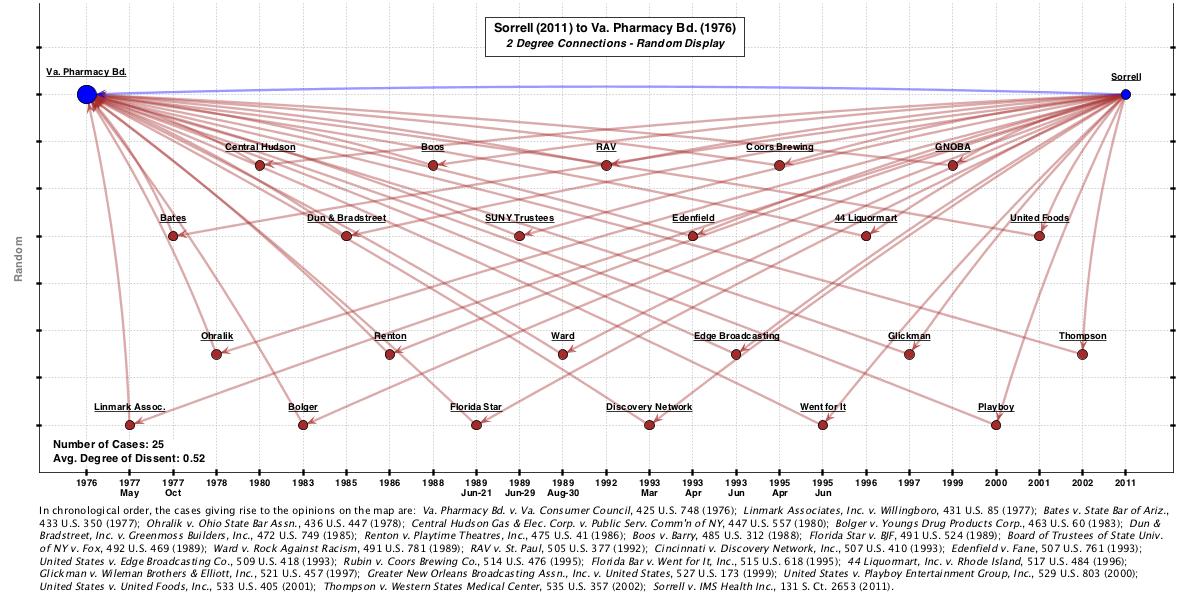

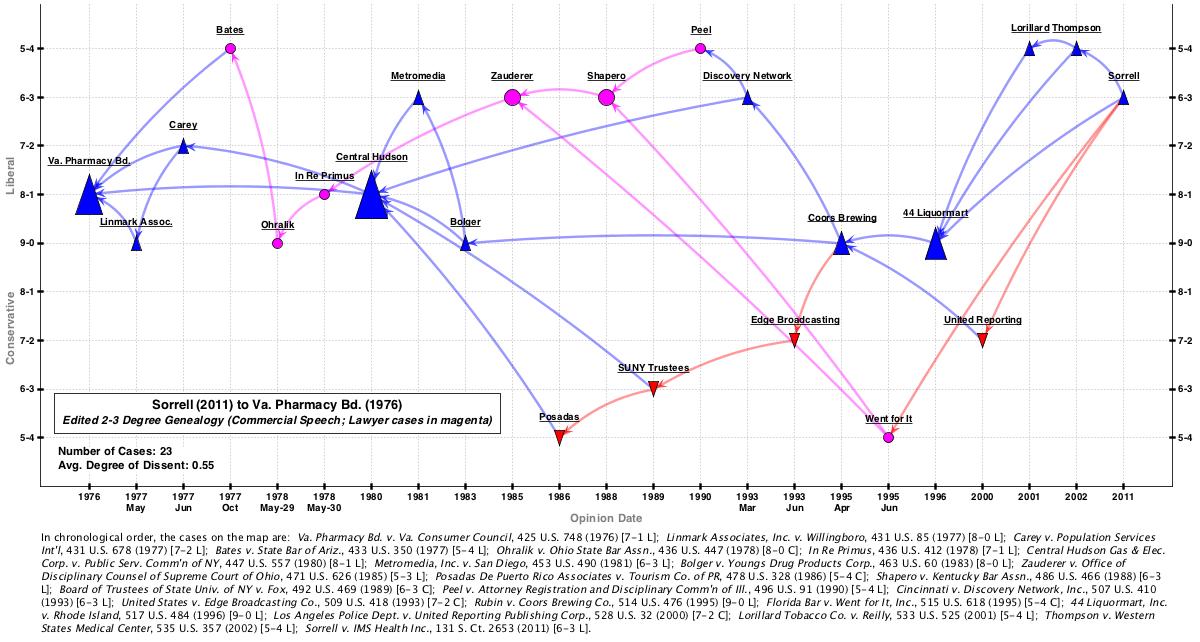

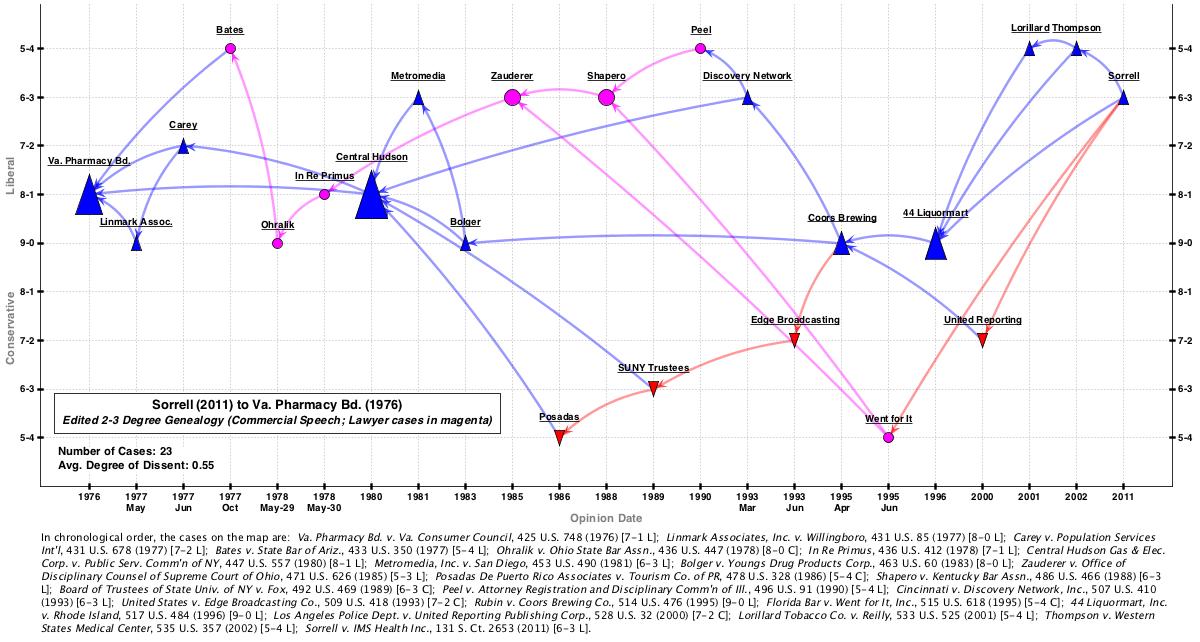

Comparing the 2- and 3-degree edited maps, one feature jumped out at me: almost half of the canonical cases missed by the 2-degree map concerned lawyer advertising (4 out of the 9 missed cases). With a little more editing, I modified the last map to highlight the lawyer advertising cases in magenta. This is the result:

With the benefit of this new visualization, we can easily appreciate how the Sullivan & Feldman text took a deeper academic dive into the lawyer advertising cases that the Sorrell opinions found necessary. It seems hard to fault Sorell for only citing 3 of the 7 cases in the magenta line.

The other 5 missed cases — Carey (1977), Metromedia (1981), Posadas (1986), United Reporting (1999), and Lorillard (2001) — are certainly important. But are they more important than the “non-canonical 7” cases referred to above? Recall those are the 7 cases included in the 2-degree network after applying the “commercial speech” filter. In other words, those are ostensibly commercial speech cases cited in Sorrell but not included in Sullivan & Feldman.

Forgive me as I dive deep into the First Amendment weeds for just a moment more and name the “non-canonical 7” cases: Dun & Bradstreet (1985), RAV (1992), Edenfield (1993), Glickman (1997), Greater New Orleans Broadcasting (1999), Playboy (2000), and United Foods (2001). Three of those cases (Dun & Bradstreet, RAV, and Playboy) certainly do not belong the main commercial speech line. But the other four do. And they are arguably as important as the 5 missed cases above.

Now let’s step back and review. Sullivan & Feldman have 23 cases in their (human created) canonical network. The machine generated 2-degree network (filtered for commercial speech) has 21 cases. 14 cases overlap between the networks and are clearly core to the line. Of the 9 cases captured by Sullivan & Feldman but not the machine, all are relevant and 5 are uniquely so. Of the 7 cases captured by the machine but not by Sullivan & Feldman, 3 are irrelevant and 4 are uniquely relevant.

All in all — Sullivan and Feldman’s editing fares better. This is as you would hope and expect. But the 2-degree network is still remarkably efficient at identifying relevant cases. (The 3-degree network, on the other hand, is far too large and unwieldy.) And the machine-generate network approach suggests potentially fruitful doctrinal angles for further reading outside of the Sullivan & Feldman line.

In the end, it bears emphasis that identifying relevant cases is very different from reading and understanding those cases. And in that department, the human editing of a casebook is completely indispensable. It would probably take 100s of extra hours to read unedited versions of cases identified by the 2-degree network. So thank your stars for human editors!