On Wednesday, September 27, 2023, CFCC hosted an important day-long symposium focused on The Harm of Removal to Children, Parents, and Communities at the University of Baltimore School of Law. This blog is one in a series of four posts about the CFCC 2023 Symposium.

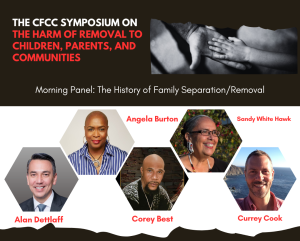

The morning’s first panel, “The History of Family Separation and Removal,” powerfully discussed the history of family separation and child removal within the context of child welfare systems. Superbly moderated by Angela Burton, the panel featured Corey Best, Currey Cook, Alan Dettlaff, and Sandy White Hawk.

The conversation explored how the history of child removal has influenced contemporary child welfare practices and called for a change in language, policies, and mindsets. Panelists discussed the need to shift the focus from preventing entry into the foster care system to preserving family integrity. They also discussed the importance of respecting the natural flow of life and encouraging change.

The panelists framed their discussion by first acknowledging that many among them have experienced the harm of removal and are healing from that harm. If not for the sake of our own integrity, we owe it to the survivors of this harm to use language that accurately reflects the past and current practices of what is known as the child welfare system. In recognition of the experiences of those impacted by the harm of removal, this summary will refer to what is known as the child welfare system as the family regulation system.

Burton explained that the stated purposes of the family regulation system, which includes ensuring safety, stability, and well-being, do not align with the practice of removal, which forcibly separates families. The family regulation system encompasses laws, policies, and practices designed to separate families and is rooted in an ideology aimed at maintaining oppression of poor, Black, Indigenous, non-heteronormative families. Burton also highlighted the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act of 1974 (CAPTA) as a key legal framework that involves surveillance and investigations of families that often lead to the state separating children from their parents, siblings, and families.

Dettlaff provided historical context to CAPTA, explaining how the identification of a new trauma diagnosis called the Battered Child Syndrome in 1962 led to mandated reporting laws and an explosion of child abuse and neglect reports, from 600 reports in 1962 to 11,000 reports in 1968.

The stats are alarming but even more sinister is how our language sterilizes the family regulation system’s racist impacts on Black and Native American children and parents. Burton challenged attendees to consider how the word “removal” sanitizes the actions of government agencies. Children aren’t removed. They are forcibly separated from their families by the state. Detltaff said there has never been a moment in our country’s history where white children were forcibly separated from their families by the state. During slavery, enslaved Black children were sold away from their families. Even after the Emancipation Proclamation, Black children continued to be separated from their families and forced into indentured servitude by their former enslavers through apprenticeship. White Hawk reflected on the long history of removal faced by Indigenous peoples. European colonizers killed Native American children and parents during acts of war, forced relocation, and genocide. Later the colonizers deliberately separated Indigenous children from their families, community, and culture by forcing them into Indian Boarding schools and targeted adoptions.

Responding to the question of what “removal” means to him, Best, who has experienced child removal as a parent, shared that child removal perpetuates fear, terror, and continued oppression and segregation that can be traced back to the arrival of the first enslaved Africans on this continent in 1619. Best pointed to the radical demographic shift in the U.S. prison population between 1861 and 1870, when the penitentiaries in southern states changed from being 90% white to 95% Black. After the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, slavery was no longer the predominant tool for separating Black children in the south from their families. Instead, racially disproportionate levels of mass incarceration effectively continued to destroy Black children’s connection to their parents. Modern day separation via the family regulation system continues the transatlantic slave trade’s legacy of terror and oppression for Black families.

Knowledge about the harms of removal has been readily available but rarely listened to. Resistance to and revelation of the harms of removal and family separation have existed since the first screams of enslaved African children and parents. Best called for the next movement in the conversation about abolition and the harm of removal to center on white people’s self-examination of their history. Best pointed out that for white folks, “there is some serviceability to this separating families. There is some serviceability to segregating bodies. There is some […] serviceability to how we continue to police Black and Brown bodies because it stems from how we love power and economics to commodify; to fill our pockets and empty our damn souls.” Best explained that we must examine the creation of whiteness to understand how to break the systems that continue to separate children and families.

Having worked in the child welfare and juvenile system, Currey exemplified the type of reflection that system actors need to engage in so that the harm of removal can be prevented, mitigated, and healed. Currey revealed that he caused a lot of harm as a young attorney who did not have lived experience in the systems in which he was working. However, he also witnessed a lot of harm that young LGBTQ+ youth experience after removal. Approximately 34% of children and youth in foster care are LGBTQ+ young people, and research shows that being in affirming homes helps LGBQ+ children thrive across a variety of domains. Currey explained that homophobia and transphobia continue to go unaddressed at the systemic level of child welfare systems. This is evidenced by the Administration for Children and Families failure to establish a nondiscrimination rule in its most recent Notice of Proposed Rulemaking. The continued cycles of misinformation and oppression have culminated in the largest number of anti-LGBTQ bills in history, with over 500 bills attempting to enshrine hate and disinformation in law.

Hope and change were the closing theme of the panel discussion. Despite the long history of family separation, change is happening now. Dettlaff said that “hope is a discipline” and that small acts of abolition are happening all around us. He shared about the initiation of the “Dads on Duty” program at a high school, which started when a school wanted to bring more police into the school because of student fights. Instead of an increased police presence, more fathers began spending time at the school. There has been a significant reduction in fighting due to the dads’ presence. “Abolition is about the presence of safety,” remarked Dettlaff.

White Hawk spoke directly to those in the social work profession who are working under supervisors and policies that hold them back from making their best decisions. She pulled from her observation of nature and how one red leaf can tell all the other leaves on a tree that it is time to change. She encouraged the audience, “Be that red leaf. Those that are called to change will follow you.” White Hawk encouraged folks to change the language they used, to encourage one another, and to lead in compassion. White Hawk closed the discussion with an invocation for reconciliation, an ancient song, and a prayer. The song said, “I want to live with my relatives, so I will pray first.”