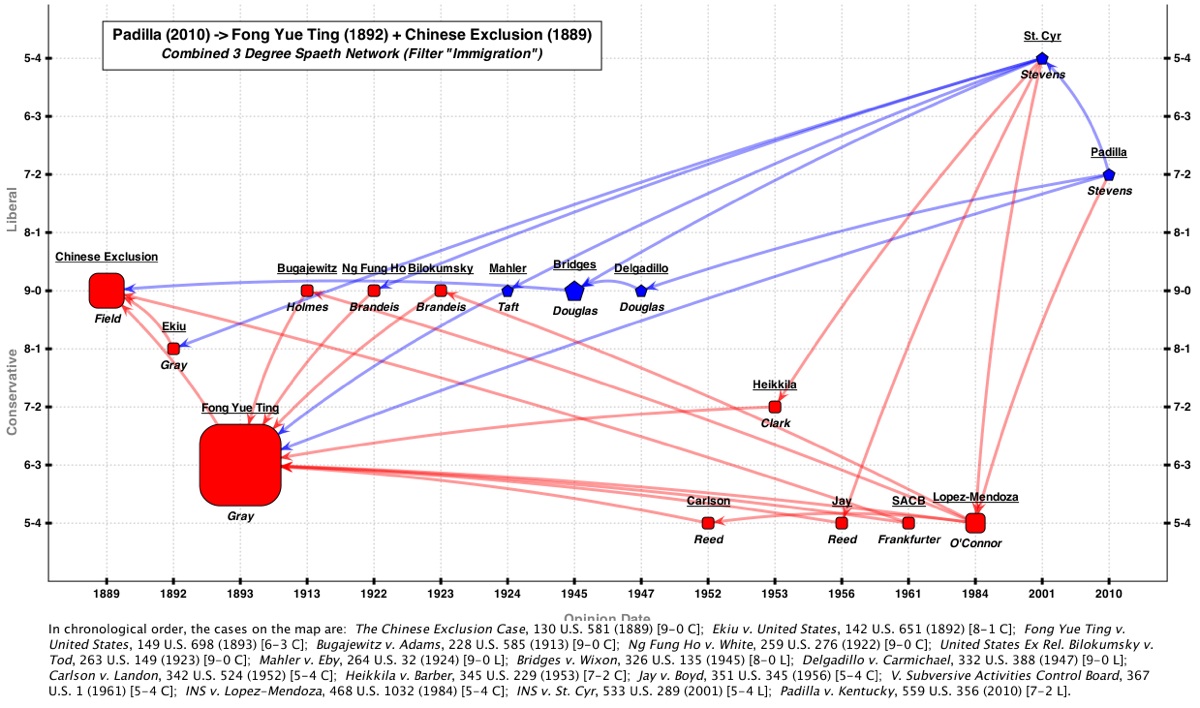

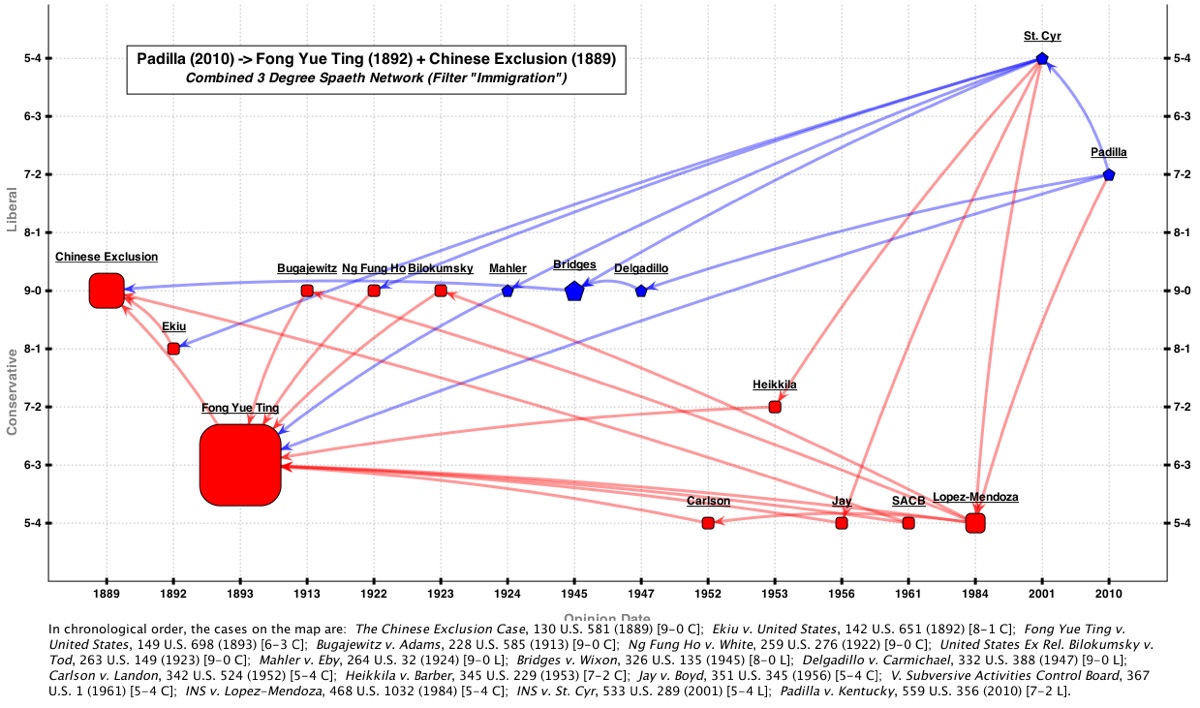

And then there was dissent! Over the past few posts (Part I here, Part II here), I’ve been modifying an automatically generated citation network map focused on immigration cases. The automatic network connected 2010’s Padilla v. Kentucky all the way back to 1889’s Chinese Exclusion Case and 1893’s Fong Yue Ting at 3 degrees. Today I switch the map’s look from a Spaeth visualization to a standard vote view (for more on “standard vote view” see Introduction to SCOTUS Mapper 1.0). Here’s the current draft image (click to see full size):

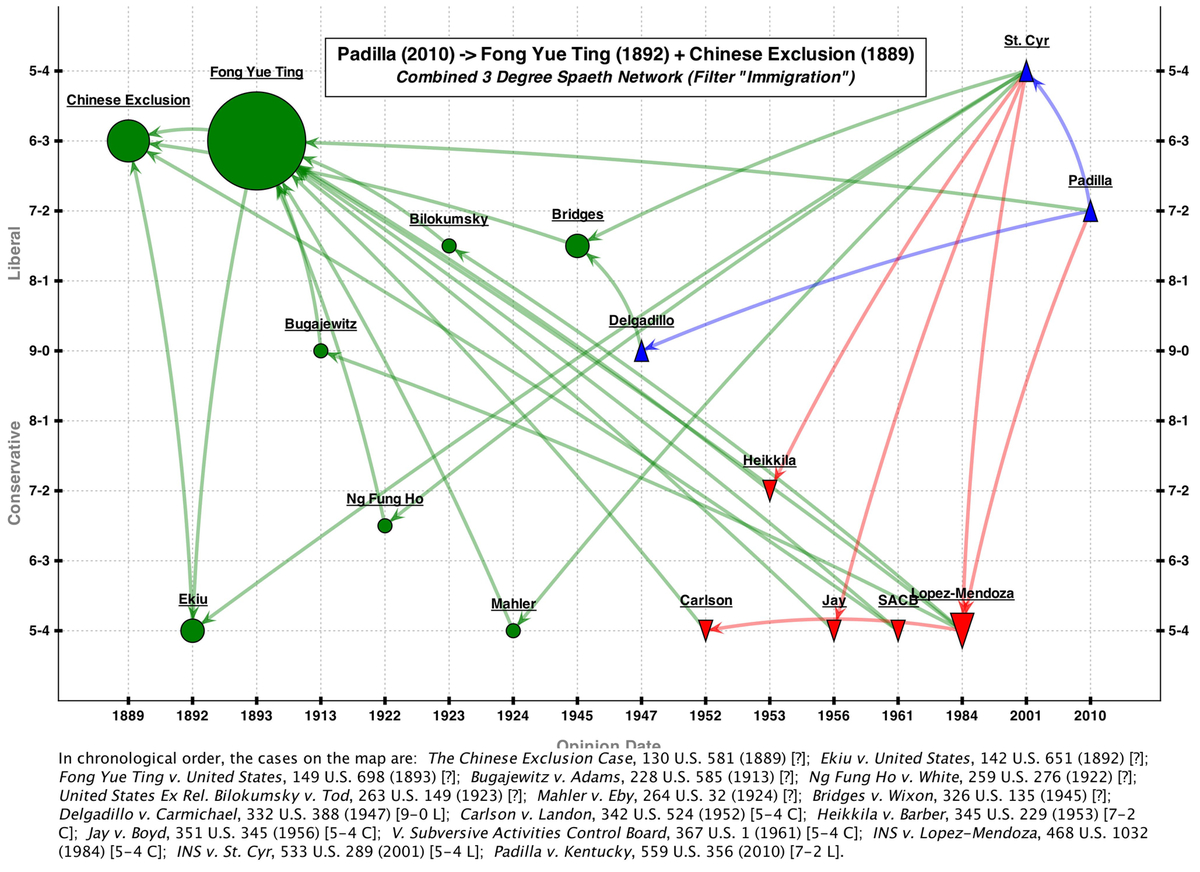

In this visualization, the Y axis represents the number of votes an opinion receives. All opinions above the dashed middle line are thus majority opinions. Dissents likewise fall below below the dashed line (as would concurring opinions were any represented). In contrast to Spaeth’s emphasis on vote coalitions for judgment, this perspective emphasizes the relative strength and weakness of particular opinions. To grasp this difference, compare this map with the original Spaeth view and contrast the relative placement of Padilla. Note how the Spaeth view represents Padilla as a 7-2 decision (the vote coalition) while the vote view represents Stevens majority opinion as only receiving 5 votes (Justice Alito and Chief Justice Roberts concurred in judgment only).

Though reclassifying existing data points like the Padilla majority opinion is useful, the most important change with the vote view is the creation of space for dissents. Going all the way back to Ekiu and Fong Yue Ting, we can immediately see that Justice Brewer promoted a different path for immigration doctrine — one that many advocates today might support. We also see an interesting cluster of dissents in the cases leading up to 1984’s Lopez-Mendoza. Justice Stevens manages to move from dissenting in that case to writing the majority opinion in St. Cyr and Padilla. (Technical note: Stevens dissent in Lopez-Mendoza and Douglas’ dissent in Jay both received 1 vote; I projected them at 1.5 votes in order to permit display of the other dissenting opinions).

Now this map is obviously incomplete. I have not attempted to integrate the pictured dissents into the existing “lines of opinions.” Doing this would allow me to trace the evolution of the competing jurisprudential schools with respect to immigration doctrine. Yet this is no easy task. Since dissents may exert influence without ever being cited, I would have to account for uncited dissents in constructing my competing lines. This requires careful reading of the opinions to parse out the essential ideas. Since I am not an immigration scholar, I am not inclined to do such heavy lifting at this juncture.

Instead, I offer the map above as proof of concept. The concept is that dissents belong in rich accounts of Supreme Court doctrine — and vote view maps provide a means to represent such accounts. If any reader of this blog wants to develop this map further, please let me know!