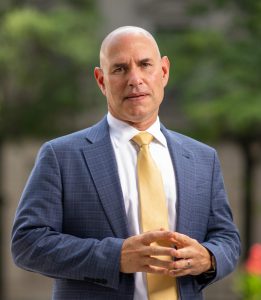

By Adam Stone

When the Key Bridge came down, Alexander Giles, J.D. ’97, got busy. He’s leveraging a broad range of legal skills to help multiple clients navigate their respective parts of that Mar. 26, 2024, disaster.

It’s perhaps not surprising that Giles should find himself in this position. Maritime law seems to have been his destiny.

“My dad was in the Coast Guard for 24 years. He served in Vietnam and retired in 1991, which was right before I went to law school,” he says. In his second year at UBalt Law, Giles took a maritime law class and knew he’d found his fit. “It was serendipity.”

His instructor introduced him to a maritime lawyer at Semmes, Bowen & Semmes, and he’s never looked back. Now at Tydings & Rosenberg, he’s one of the premier maritime attorneys in the nation.

Giles says he represents “the 800-pound gorillas in the Port of Baltimore, the most obvious one being Ports America Chesapeake.” The other emerging heavyweight is Tradepoint Atlantic.

Among these big players, maritime legal issues can run the gamut. “Think about all the laws that affect people on land. You have all of that in maritime law, you’re just dealing with ocean commerce. You’re dealing with incidents that happen on the water,” he says.

In practical terms, “it’s anything from corporate-type issues to personal injury to cargo damage,” he says. “You can have employment law issues, workers’ comp issues, wrongful death issues, personal injury issues, contract issues, theft of cargo, and criminal actions as well.”

With the collapse of the Key Bridge, Giles has had to bring all those skills to the table.

“I’ve got several clients that are involved. Ports America, for example, is where the ship that struck the bridge left from, and that’s where the ship had been docked. They don’t have any suspected liability, but with the NTSB and U.S. Coast Guard and FBI investigations, there were a lot of touchpoints in terms of what they knew, and what they didn’t know,” he says.

Tradepoint Atlantic stepped in when the bridge went down, paving lots to use as laydown space for all the steel that needed to be moved from the channel. They also agreed to take and unload numerous ships destined for other terminals located inside the Key Bridge. Another client, McAllister Towing, had two tugs guiding the M/V Dali, the massive container ship that struck the bridge, during the early morning hours in question.

“The tugs were released by the pilot about 20 minutes before the ship hit the bridge, so they should not have any liability or exposure,” he says. But with repairs estimated at $1.9 billion, “there’s a big delta there between what sort of money may be available from litigation, as opposed to what money is needed to rebuild the bridge.”

That means he has a lot of work to do to demonstrate that his client is not, and should not be, on the hook for any of that funding.

In an incident as big as this one, Giles says, “It could be its own bar exam in terms of all the legal issues that are involved,” he says. To succeed as a lawyer in this environment, “You have to have a broad knowledge of all the laws that could be implicated. You need to know all the issues, because the issues all impact each other.”

Water and Wind

The Key Bridge incident is only one of the things keeping Giles busy these days. He’s also deeply involved in the legal work needed to bring to life offshore wind farms off the Maryland coast. Here, too, complexity is a dominant theme.

“There are a lot of pieces that go into making offshore wind successful,” he says. “My involvement has been on the maritime side: In terms of assessing navigability, pathways for commercial vessels, and how the lease space affects or doesn’t affect those pathways.”

The U.S. Coast Guard is involved, and the Jones Act also comes into play. That’s a federal law requiring goods shipped between U.S. ports to be transported on ships that are built, owned and operated by Americans. The law will impact what vessels may be used for the anticipated construction and installation of offshore wind turbines.

Offshore wind power “is going to happen in Maryland, just like it will in all the other states up and down the East Coast. It’s just going to take a little time,” he says.

Giles says his University of Baltimore experience prepared him well for the demands of a career in maritime law.

“One of the reasons I chose University of Baltimore was because it had a reputation of looking at things from a practical standpoint: Here’s how you practice law, but here’s what really happens,” he says.

“In my three years of law school I learned what happens in court, what happens when you work up a case, how to achieve the best result for your client — both from a legal perspective and also a business perspective,” he says. That kind of education “really helped me understand how to be effective for my clients.”

Adam Stone is a writer based in Annapolis.

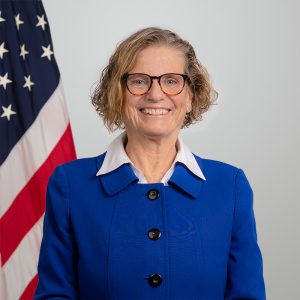

Photo by Larry Canner.

The idea for the series ignited when Chambers talked to best-selling crime novelist George Pelecanos, also D.C.-based, about the difficulty in telling a gritty story about a capital city that’s increasingly gentrified. “He said:

The idea for the series ignited when Chambers talked to best-selling crime novelist George Pelecanos, also D.C.-based, about the difficulty in telling a gritty story about a capital city that’s increasingly gentrified. “He said: