By Hope Keller

In 2017, on the day the consent decree between the U.S. Department of Justice and the city of Baltimore and its police department was filed in court, then-U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch spoke at the University of Baltimore School of Law.

She began by noting that she took her oath of office on the day Baltimore erupted over Freddie Gray’s death in police custody.

“It was clear that here in Baltimore – as in so many American cities – deep-seated feelings of mistrust and hostility had gone unaddressed for too long,” Lynch said on Jan. 12, 2017. “And it was clear that in order to repair the social fabric, those issues had to be dealt with honestly, comprehensively and immediately.”

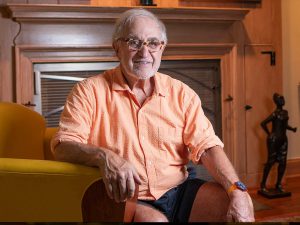

Against this backdrop, the UBalt School of Law this year launched the Center for Criminal Justice Reform (CCJR). Created with a $3 million gift from alumnus Samuel G. Rose, LL.B. ’62, the center supports community-driven efforts to improve public safety and address the harm and inequity caused by the criminal legal system. (A companion Criminal Defense and Advocacy Clinic, which begins in Spring 2023, was also created thanks to Rose’s bequest.)

Heather Warnken, executive director of the center, said it is engaging in a range of programming meant to address the mass incarceration crisis, and to reimagine public safety across the country. Part of this work means rethinking the definition of “crime victim” to build a more inclusive infrastructure of care.

“Historically, the idea of ‘crime victim’ [conjures] certain images and does not include the experience of Black men and youth who, by exponents, experience the most homicide and nonfatal gun violence in this country, including in Baltimore,” Warnken says, “yet are more likely to be criminalized than supported in the aftermath of that violence.”

Prof. David Jaros, the center’s faculty director, said he and Warnken sought to break down the “false dichotomy” between crime victims and the defendants who disproportionately wind up enmeshed in the criminal legal system.

“In fact, these are all the same people,” Jaros says. “Our system tends to divide [people] up into communities worthy of protection and respect for their rights and communities that don’t get the resources or protection of the legal system.”

Moreover, trauma begets more trauma, notes Warnken. “For people who experience violence and harm in their communities, especially in the absence of meaningful, humane, dignified responses that support them — the likelihood that they will be a victim or they will harm others is greater,” Warnken says. “Being serious about public safety means embracing what we know actually works in interrupting cycles of harm — and the systemic racism that perpetuates it.”

‘The Web of disparities’

Warnken and Jaros say the CCJR will regularly convene community and government stakeholders to identify challenges and recommend solutions to the deeply entrenched inequities in the national and local criminal legal systems.

Before coming to the law school, Warnken spent five years as a visiting fellow at the U.S. Department of Justice, where she was co-affiliated with the Bureau of Justice Statistics and Office for Victims of Crime in the first-ever position dedicated to bridging the gap between research, policy and practice to improve the response to individuals and communities impacted by crime victimization.

In that role, Warnken led an assessment of how people impacted by violence are treated in Baltimore. The report authored by her and her team — which examined the experiences of underserved survivors, focused on Black men and youth affected by gun violence — was released by the City of Baltimore in August, along with a formal response.

The report made clear that to improve public safety in Baltimore, the legacy of racism in policing must be confronted head-on.

The historical role that law enforcement played in maintaining slavery through slave patrols came up in multiple interviews, according to the report.

“It is obvious to many that Black and brown bodies have been historically viewed as a threat by law enforcement and, in society more broadly, less worthy of compassion in the wake of harm if worthy at all,” the report said in its first chapter. “These persistent attitudes undergird the web of disparities found throughout public life, including a sense of continued impunity for disparate or dehumanizing treatment from BPD.”

At a center event in February, former DOJ Inspector General Michael Bromwich, who led a two-year investigation into the Baltimore Police Department’s disgraced Gun Trace Task Force, presented his team’s findings. The video of the event had been viewed more than 11,000 times as of late October, no doubt thanks to “We Own This City,” the HBO series about the GTTF adapted from Baltimore crime reporter Justin Fenton’s book of the same name.

For years, members of the elite police unit robbed Baltimore residents and planted guns and drugs. They were arrested in 2017 and ultimately convicted on charges of racketeering, robbery, extortion and overtime fraud.

Saying the scandal was emblematic of deeper, systemic challenges in policing, Warnken says the CCJR will look into the role of judges and other key actors in responding to police misconduct.

“We’re really interested in the role of judges, who make decisions every day in their courtrooms — interpreting evidence and [determining] the truthfulness and reliability of officers — reliability that is often given great weight,” Warnken says.

The center is also involved in projects examining equity in public safety grantmaking, including how federal criminal justice grants are spent, Warnken adds.

“State and local governments get a tremendous amount of money from the Department of Justice and other federal agencies,” says Warnken. “Are they relying on police and prosecution, or are they meaningfully investing in community-based programs and alternatives to incarceration? There’s so much discretion at the state and local levels, but not enough support or transparency on how those dollars get spent.”

Benefactor Samuel Rose said in a University of Baltimore School of Law news release that the center would benefit reform efforts locally and nationally.

“It’s both exciting and gratifying to support efforts to improve the lives of individuals — the wrongly accused and the excessively punished — while working more broadly to influence local and national policy around violence prevention, mass incarceration, juvenile justice and more,” he said.

Dean Ronald Weich said the Center for Criminal Justice Reform was a logical outgrowth of the law school’s longstanding involvement in criminal justice matters.

“Some of the best defense lawyers are UB graduates, half of the state’s attorneys in Maryland are UB graduates,” Weich said. “This is a more comprehensive way of addressing issues related to criminal justice, from policing to sentencing to victims’ rights.”

And, he said, the law school is a perfect place for such a center.

“If you want to work on improving criminal justice, the University of Baltimore is the place to do it,” Weich says. “We are proud to support community-driven reform efforts in Baltimore and beyond.”

Hope Keller is a writer based in Connecticut.