By Matthew Liptak

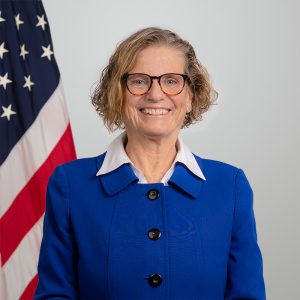

If you ask Michelle McGeogh, J.D. ’07, why she does so much pro bono work, she has a quick answer.

“There are a lot of reasons why I do pro bono work, but to me the harder question is, why would anyone not do pro bono work?,” McGeogh says. “It’s fairly obvious that there’s unequal access to justice in our community, and across the country, and across the world.”

McGeogh is married with two daughters, but the Baltimore lawyer said integrating pro bono work into her 16-year career as an attorney has helped keep her grounded. Her parents are U.S. Army veterans and medical doctors, so service was part of her life from a young age.

Recently she brought her young daughter to court to observe a sentence modification hearing for a pro bono client who had received a life sentence. And pro bono work is often a big part of everyday conversations with her family, she says.

McGeogh was named co-chair this year of Maryland Legal Aid’s Equal Justice Council. That’s just a year after joining the board of directors of the Maryland Volunteer Lawyers Service (MVLS). She is just one of the graduates of UBalt Law who are devoting much of their careers to advancing the cause of equity in our justice system.

“I went to law school to make a difference,” she says, “and it’s really pro bono work that allows me to make an impact.”

McGeogh is a partner at Ballard Spahr, where she focuses on real estate and construction litigation and employment law. She praises the firm for allowing all pro bono work to count toward attorneys’ billable hours budget, with no cap. “In short, pro bono work is treated like billable work at Ballard Spahr,” she says.

“I think there’s a trend toward more firms offering policies like that,” she explains. “Every law student I interview will ask about the pro bono program. I’d like to see other firms follow suit. It’s a recruiting tool.”

As champions of pro bono, McGeogh, along with UBalt Law alumnae Susan Francis, J.D. ’11, and Vicki Schultz, J.D. ’89, recognize the importance of attorneys giving their time and talent to those in need.

Schultz is executive director of Maryland Legal Aid, the largest provider of free legal services in Maryland, with 12 offices around the state.

“It’s very important that people have representation,” she says. “When they don’t, there are often dire consequences. They may lose their home. They may end up homeless. They may not be able to eat. They may lose their jobs. When you step in as a pro bono lawyer, you can help someone meet their most basic needs.”

“If the legal system is only is going to work for those who have money to hire an attorney, then it really goes to the heart of the credibility of our justice system,” says Francis, who is executive director of MVLS. “It diminishes our system of justice, and as attorneys and legal services providers, that’s what we seek: an equitable judicial system.”

According to the Maryland Access to Justice Commission, there are over 10,000 unserved low-income clients in need in our state for every 1½ legal services attorneys, Schultz says. Maryland is listed as one of the better performing states in the nation.

“Pro bono is hugely important,” Schultz says. “There is an incredible need for civil legal aid for people who can’t afford a lawyer.”

The disparity is huge, and, although some pro bono lawyers are giving their time and talent, many other Maryland attorneys volunteer little or not at all. “I think if everyone chipped in a bit more, we would get closer to meeting that need,” McGeogh says.

According to Francis, McGeogh is an example to firm partners and associates about prioritizing pro bono while excelling in your career. “Michelle, despite her very successful and busy career, makes time to do pro bono herself, mentors numerous associates in her firm to do pro bono, and consistently provides her limited time and numerous talents to further the important work of the MVLS board,” Francis says.

Pro bono advocates say that time constraints are one of the reasons attorneys don’t donate more of their time. Pro bono work is included in the code of ethics for Maryland lawyers, but many don’t prioritize it. The Maryland Pro Bono Resource Center, in partnership with the Maryland State Bar Association, has issued a Pro Bono Call to Action, with a simple signup form to encourage lawyers to give their time.

There are plenty of ways for a lawyer to give back. And the benefits of volunteering are also abundant. McGeogh, Schultz and Francis all say heartfelt appreciation from clients is a real motivator for pro bono attorneys to continue volunteering their time.

And the experience one can get is hard to match in the legal field. “I think doing pro bono work makes you a better lawyer,” McGeogh says. “You can take on pro bono matters as a very junior lawyer and get to take the lead on it.”

Francis noted one recent example, where a new associate in a large firm had the opportunity to argue a pro bono case in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. After the argument, this associate was approached by a partner in the firm, who was seeking advice because the partner hadn’t argued before that court before. “It was great experience for the associate,” says Francis, “and it helped her build recognition within the firm.”

But for McGeogh and her fellow UBalt Law alumni, the best reward remains serving neighbors while contributing to the justice system they are working to improve.

“You’re not necessarily changing the world,” McGeogh says, “but it’s one little step toward making the world a little more fair for someone else.”

Matthew Liptak writes from Severna Park, Md.

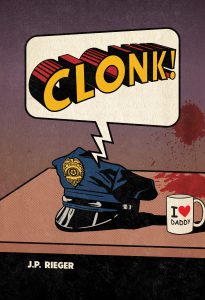

The idea for the series ignited when Chambers talked to best-selling crime novelist George Pelecanos, also D.C.-based, about the difficulty in telling a gritty story about a capital city that’s increasingly gentrified. “He said:

The idea for the series ignited when Chambers talked to best-selling crime novelist George Pelecanos, also D.C.-based, about the difficulty in telling a gritty story about a capital city that’s increasingly gentrified. “He said: