As a third-year law student, I have spent much of my last three years improving my writing skills; however, I still find that I express myself better orally. Perhaps this is because of tone, enunciation, or other aspects unique to the oral verbalization of words. It may also be due to my own individual thought process, in which I find it easier to learn through listening and to read back things aloud. Whatever the reason, I thought that exploring this through technology would be an interesting topic. Speech-to-text software gives us the ability to speak our words to the page, so I have spent the past few weeks using this software as part of this exploration. This all being in an effort to answer the titular question: is speech-to-text software an effective tool for legal writing?

The software in which I chose to use is Nuance Dragon Professional Individual. This software was chosen primarily because of its popularity, but also due to recommendations from colleagues. The software was relatively easy to install and provided a brief tutorial upon installation. This tutorial informed you of the syntax needed in order to have commas, periods, new lines, etc. My initial impression of this was that saying things like “comma” or “new line” was not very intuitive; however, over time this became something I got used to. The tutorial also provided you with menus that you could open for editing purposes, quick correction tools, and various other ease-of-access resources that were all accessible through pre-set oral commands.

After I had completed the tutorial, I began testing the software in detail. I was thoroughly impressed with the accuracy given my first initial tests were in a loud room while using a relatively inexpensive microphone. Since then, I have exclusively used the software in a quiet setting with a more professional microphone and have not had any significant issues with accuracy, although it is far from perfect.

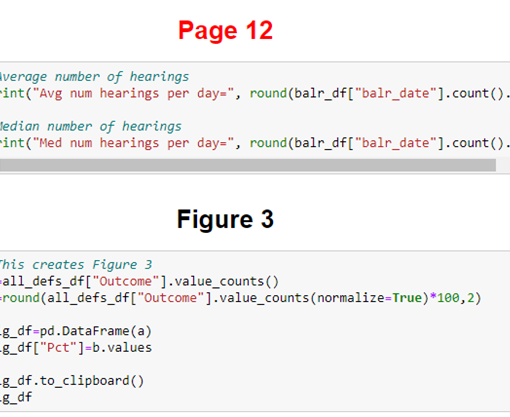

In order to best show you the accuracy of the software, this entire next paragraph, including the current sentence will be written using the software. I started writing this paragraph at 8:15 PM and will tell you the exact time it took me to complete it, including using the software to make edits to any mistakes that were made. I also wish to show you in this paragraph that words can be underlined, bolded, italicized, etc. This first part of the sentence is underlined, while the second part of this sentence is bolded, and the third part of this sentence is italicized. It is also possible to create -hyphens-, :colons:, (parenthesis), and so forth. It is currently 8:27 PM, so the total time that it took me to “write” this paragraph, and make all applicable edits was 12 minutes.

One other test that I wish to provide for the purpose of this exploration is the reading of a court opinion. As a law student, much of my time is spent doing legal writing, so how would the software fair in that setting? Given this, I thought there would be no better opinion than one from Justice Cardozo himself: Palsgraf v. Long Island Railroad Co.

Below is the last paragraph from the majority opinion as written:

“The law of causation, remote or proximate, is thus foreign to the case before us. The question of liability is always anterior to the question of the measure of the consequences that go with liability. If there is no tort to be redressed, there is no occasion to consider what damage might be recovered if there were a finding of a tort. We may assume, without deciding, that negligence, not at large or in the abstract, but in relation to the plaintiff, would entail liability for any and all consequences, however novel or extraordinary (Bird v. St. Paul F. & M. Ins. Co., 224 N. Y. 47, 54; Ehrgott v. Mayor, etc., of N. Y., 96 N. Y. 264; Smith v. London & S. W. Ry. Co., L. R. 6 C. P. 14; 1 Beven, Negligence, 106; Street, op. cit. vol. 1, p. 90; Green, Rationale of Proximate Cause, pp. 88, 118; cf. Matter of Polemis, L. R. 1921, 3 K. B. 560; 44 Law Quarterly Review, 142). There is room for [*347] argument that a distinction is to be drawn according to the diversity of interests invaded by the act, as where conduct negligent in that it threatens an insignificant invasion of an interest in property results in an unforseeable invasion of an interest of another order, as, e. g., one of bodily security. Perhaps other distinctions may be necessary. We do not go into the question now. The consequences to be followed must first be rooted in a wrong. The judgment of the Appellate Division and that of the Trial Term should be reversed, and the complaint dismissed, with costs in all courts.”[1]

Now below is a reading of the above paragraph using the software, with no edits having been made:

“The law of causation, remote or proximate, is thus foreign to the case before us. The question of liability is always anterior to the question of the measure of the consequences that go with liability. If there is no tort to be redressed, there is no occasion to consider what damage might be recovered if there were a finding of a tort. We may assume without deciding, that negligence, not at large or in the abstract, but in relation to the plaintiff, would entail liability for any and all consequences, however novel or extraordinary (Bird V. St. Paul F. & M. INS. Co., 224N. Y. 47, 54; ergo Mayor, etc., Of N. Y., 96 and. Y. 264; Smith V. London & S. W. RY. Co., L. R. 6C. P. 14; 1 Beven, negligence, 106; Street, OP. CIT. The OL. One, P. 90; Green, rationale of proximate cause, PP. 88, 118; cf. Matter of hollowness, L. R. 1921, 3K. B. 560; 44 Law quarterly review, 142). There is room for argument that a distinction is to be drawn according to the diversity of interests invaded by the act, as were conduct negligent and that it threatens an insignificant invasion of an interest in property results in an unforeseeable invasion of an interest of another order, as, E. G., One of the bodily security. Perhaps other distinctions may be necessary. We do not go into the question now. The consequences to be followed must first be rooted in a wrong. The judgment of the Appellate Division and not of the trial term should be reversed, and the complaint dismissed, with all costs in all courts.”

As one can see, the general language remained relatively intact, but the legal citation ended up with many mistakes that would have normally needed editing. This seems like a fair outcome given that legal citations can be difficult when written normally regardless. However, it is clear that this is far from perfect.

Once again, I ask the titular question of: is speech-to-text software an effective tool for legal writing? Like many answers in the legal world, my answer is that it depends. The tools that the software provide are useful and do not take long to grow accustomed to; however, taking 12 minutes to produce a relatively simple paragraph is certainly less than ideal. While the software ran into trouble in replicating an accurate legal citation, it did succeed in articulating the complex and intricate language that Justice Cardozo is known for in his opinions. Overall, I do believe that speech-to-text software does have a place in the legal writing world, but mostly as an adequate alternative for those that may need it.

[1] Palsgraf v. Long Island R.R. Co., 162 N.E. 99 (N.Y. 1928).