On July 1, 2017, a new law went into effect in the state of Maryland. It sought to curb the number of defendants being held in Maryland jails for an inability to pay bail. Now, two and half years later, how much has bail reform helped the underprivileged and poor in Maryland? According to data obtained from Professor Colin Starger at the University of Baltimore School of Law, the percentage of defendants in pretrial detention has almost doubled since the passage of bail reform.[1]

Rising inequality amongst incarcerated defendants unable to pay bail was one of the reasons Attorney General Brian Frosh championed this bill. Now, as we can see from the data, this rule did not do as promised to help stop the rising number of pretrial incarcerations.

The Basics of Bail

After a person is arrested and booked, they go before a District Court Commissioner.[2] Through the use of risk assessment tools, the commissioner determines if the defendant poses a flight risk or a risk to public safety.[3] If the defendant is not released by the commissioner (i.e. the defendant is held without bail).[4] The next business day, the defendant will go before a District Court Judge for a bail review hearing.[5]

When the defendant is before either the commissioner or the judge, there are four possible outcomes: (1) the defendant will be detained in jail until their trial without being provided an option to pay bail as a condition of release (HWOB, Detained without Bail); (2) the defendant is allowed to pay bail as a condition to release, but is otherwise detained if the defendant does not pay bail, (HDOB, Offered Bail); (3) the defendant is released on recognizance, promising that they will appear in court (ROR, Released); or (4) the defendant is held on an unsecured personal bond, meaning they are released but sign a contract to appear in court. If they fail to appear, they promise to pay the agreed upon bail amount. (UPB, Released with Promise to Pay).[6]

A New Bail Rule

Maryland Rule 4-216.1 issued on July 1, 2017, was designed to “reduce the jail population and eliminate excessive cash bails for the poor in Maryland” following an opinion from Maryland Attorney General Brian E. Frosh (D) “that cash bail is unconstitutional because it unfairly keeps some people in jail for months until trial while others similarly charged can pay to go free.”[7]

The resulting data from cases between July 1, 2015 and July 1, 2019 reveal that the rule did not have the intended consequences. Specifically, after the rule, judges are more likely to order a defendant to be jailed without the option to pay bail and be released, and fewer judges are providing a bail option for defendants. More specifically, 25.4% more suspects are detained without the option to pay bail than they were before the rule, and 33.49% fewer suspects are provided a bail option after the rule. See the data summary below:

|

Bailment Option |

Instances Before Rule | Instances After Rule | % Instances Before Rule | % Instances After Rule | % Change After the Rule |

| Held Defendant on Bail | 28,906 | 7,755 | 47.23% | 13.74% | – 33.26% |

| Held Without Bail | 11,755 | 25,189 | 19.21% | 44.61% | + 25.40 % |

| Release on Recognizance | 18,523 | 19,688 | 30.26% | 34.87% | + 4.61% |

| Unsecured Personal Bond | 2,023 | 3,829 | 3.31% | 6.78% | + 3.47% |

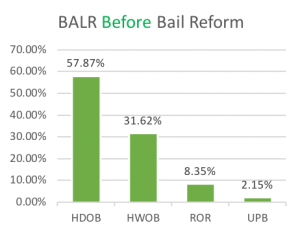

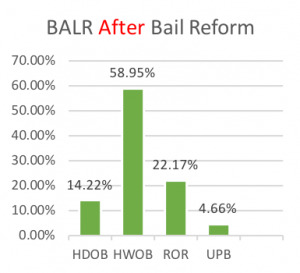

Although the data reveals a decrease in the use of cash bail after the rule change, it simultaneously shows an increase in defendants being detained in jail without a bail option. Judges are now completely eliminating any chance at even paying to get freedom. The attached charts show how much of a drastic change there has been in the time period before and after the rule change.

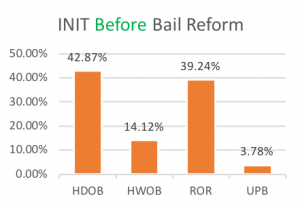

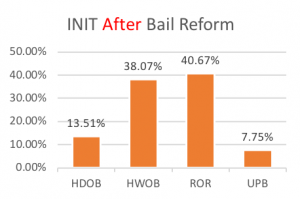

The Initial Decisions Made By the Commissioner (INIT)

Before the rule reform, out of 43,421 total defendants, 42.87% or 18,613 defendants were offered cash bail as a condition to release, and 14.12% or 6,131 defendants were jailed without an option of bail.

Yet, out of 38,760 total defendants, after the rule reform, the number of defendants held without bail more than doubled (38.07% or 14,754 defendants), and the number of defendants offered bail reduced by more than half (13.51% or 5,238 defendants).

Decisions Made By the District Court Judge (BALR)

Before the rule reform, out of 17,786 total defendants, 57.8% or 10,293 defendants were offered bail as a condition to release, and 31.62% or 5,624 defendants were detained without an option of bail.

Yet, out of 17,701 total defendants, after the rule reform, the number of defendants detained without the option to pay bail doubled (58.95% or 10,435 defendants) and the number of defendants offered bail as a condition of release reduced by more than half (14.22% or 2,517 defendants).

The Minority Report Effect

A question that should be is asked is, “Why are judges not releasing people?” Fear of crime is the answer. The fear of pretrial violence drives judges across the country to detain people who they fear are a risk. This can be seen as a way of protecting the community by stopping potential crimes. On the other hand, it keeps defendants in jail for crimes they have not and will never commit. Judges sometimes use algorithms to quantify a particular person’s risk of pretrial violence.[8] According to critics of algorithmic systems used to assess the risk of violence, Pretrial incarceration rates in America are extraordinarily high due to an inflated sense of the risk of pretrial violence.[9]

The 2002 hit movie Minority Report touched on the subject of predicting criminal activity using technology. Set in a dystopian future, police predict and stop criminal activity before it even occurs. While a proactive arrest scheme makes an ideal movie premise, it is not an ideal way to protect society with our limited technology, even ignoring the myriad of constitutional rights arguments raised by this practice. Predicting whether someone will or will not break the law if released is a complex question that cannot be predicted easily, even with the most sophisticated software available today.[10]

When a bail reform rule coupled with risk assessment tools fails to reduce the number of people being held in jail, it indicates that the bail reform rule did not work. The bail rule was meant to help defendants who were not able to afford bail. Instead it has led to defendants not even being offered bail, but instead to defendants being ordered into pretrial detention.

Bail in 2020 and Beyond

The increased numbers of defendants held without bail in Baltimore City illuminates the importance of considering the possible harmful unintended consequences of a policy decision. Judges are now holding more defendants without bail as is seen above, and it has evened out in the number of defendants being incarcerated.

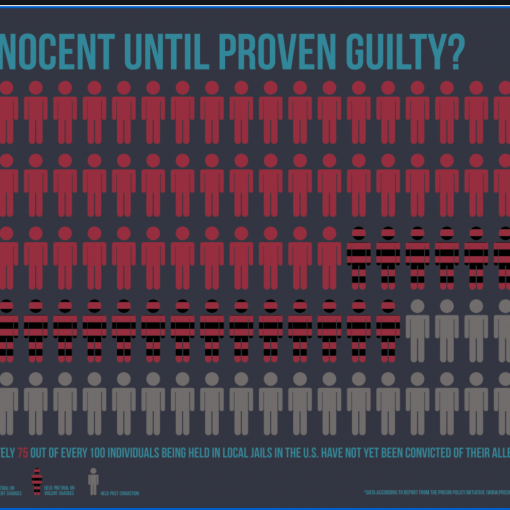

Pre-trial incarceration is a problem in Maryland and across the United States that still needs a lot of work to solve. As of March 2020, New York, New Jersey and California passed rules that will end cash bail. Six out of 10 people in U.S. jails—nearly a half-million individuals on any given day—are awaiting trial. These are people who are presumed to be innocent of the charges against them, yet they account for 95% of all jail population growth between 2000-2014.[11]

A system where the amount of money you have on hand dictates your freedom seems unconstitutional.[12] The intent behind the new bail reform rule in Maryland is a step in the right direction, but its implementation requires much more work in order to result in greater equality in pre-trial justice for Marylanders.

[1] See Chelsea Barabas, Karthik Dinakar, Colin Doyle, The Problems with Risk Assessment Tools, N.Y. Times, Jul. 17, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/17/opinion/pretrial-ai.html

[2] See id.

[3] See id.

[4] Why We Need Pretrial Reform, https://www.pretrial.org/get-involved/learn-more/why-we-need-pretrial-reform/ (Last visited on March 11, 2020)

[5] Roxanna Asgarian, The Controversy over New York’s Bail Reform Law, Explained, https://www.vox.com/identities/2020/1/17/21068807/new-york-bail-reform-law-explained (Last visited on March 4, 2020)

[6] An Analysis of the Application of the July 1, 2017 Cash Bail Rule Across Anne Arundel County, Baltimore City, and Prince George’s County 3 (2019)

[7] Lynh Bui, Reforms intended to end excessive cash bail in Md. are keeping more in jail longer, report says, Wash. Post, Jul. 2, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/public-safety/reforms-intended-to-end-excessive-cash-bail-in-md-are-keeping-more-in-jail-longer-report-says/2018/07/02/bb97b306-731d-11e8-b4b7-308400242c2e_story.html. (Last visited March 4, 2020)

[8] See Chelsea Barabas, Karthik Dinakar, Colin Doyle, The Problems with Risk Assessment Tools, N.Y. Times, Jul. 17, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/17/opinion/pretrial-ai.html

[9] See id.

[10] See id.

[11] Why We Need Pretrial Reform, https://www.pretrial.org/get-involved/learn-more/why-we-need-pretrial-reform/ (Last visited on March 11, 2020)

[12] Roxanna Asgarian, The Controversy over New York’s Bail Reform Law, Explained, https://www.vox.com/identities/2020/1/17/21068807/new-york-bail-reform-law-explained (Last visited on March 4, 2020)