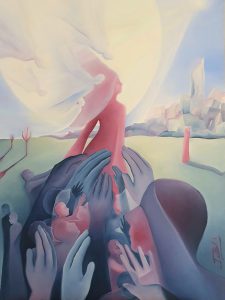

Verso la Luce by Delta NA

Mommy-I-Mean-Aunt

Katherine Varga

The first time I told my mom “I don’t want kids”, she encouraged me to want them anyway.

I didn’t mention climate change or fascism. I didn’t explain that I already spend enough time terrified people I love will die without adding a child to my roster of anxieties.

Nor did I remind her that when I learned how babies are made in 8th grade health class, 13-year-old me told her it sounded awful, and she told me, “You’ll change your mind when you’re older,” but almost-30-year-old-me has the same mind. Everything from buying new clothes to scheduling doctor appointments to vomiting in the morning— not to mention the reproductive act itself, which my body doesn’t intuitively desire— sounds to me like more trouble than it’s worth.

But I didn’t go into details with her. I just told her I didn’t want kids.

“Think of all the material for writing having kids would give you!” As if it were reasonable to create an entire human for the story ideas.

My older sister has two children. When her first was born three years ago, I saw how eager Mom-as-Grandma was to change diapers, to put him to sleep, to put a towel on her shoulder and let him spit on it—anything to be close to this new person who looks like our family. I saw what I’m denying her.

“Are you Mommy or Aunt Katherine?” my sister’s 3-year-old, Noah, asked her as she buckled the belt in his car seat.

My sister and her husband were going to Maine for the week, just the two of them. I drove from upstate New York to Connecticut to help our parents babysit. I hadn’t seen my sister’s family since Christmas. Her 1-year-old was a stranger, peering up at me from his stroller with an entire torso and legs that hadn’t been capable of carrying him last time I saw him.

On Monday, my parents and I brought the kids to a nearby park. Noah and I played racecars and ran throughout the playscape. After what felt like all day, we went home. It wasn’t even 10:30am. Noah still had smudges of sunscreen on his face that I hadn’t been able to fully rub in, due to his squirming. Now he wanted to stack wooden blocks and knock them over with his fire truck, over and over again.

“Why do people do this?” I asked my mom.

For a second my mom seemed delighted, like I had said what she was thinking. But she kept a straight face and said it’s easier when you’re working full time. You’re away from the kids all day, so you enjoy them when you do see them in the evening and weekends.

“I can’t imagine doing this on top of my job,” I said.

Not that I didn’t love reading Noah book after book at bedtime, asking him to name trucks and animals. Or hoisting baby Eli into the booster seat and cutting his watermelon into bite-sized pieces. I didn’t even mind dumping the urine and poop out of the kid’s potty into the flushable one. I loved taking care of them so much that it took up all my energy.

Throughout the week, Noah accidentally called me Mommy. I kept correcting him, until by Friday, he would catch himself: “Mommy-I-mean-Aunt-Katherine.”

Whenever the kids napped and I had a moment to myself, I curled up with In Defense of Witches by Mona Chollet and read about how society demonizes women who don’t want children. A happily single woman must be dangerous. She must hate children. If a woman doesn’t want or is unable to give birth, what is even the point of her existence? Throw her in the oven!

“The kids like you. I don’t think they like me,” my mom said. Then she caught herself. “Well, I guess kids tend to gravitate towards younger people in the room.”

“Plus I look like their mom,” I pointed out.

“And sound like her,” Mom said. “Earlier today, I thought you were her.”

I didn’t have much practice talking to 3-year-olds so I imitated my sister’s kind, patient tone. If I didn’t know better, I would have mistaken myself for her too.

On Thursday, while the kids were sleeping, my mom and I relaxed in the living room and talked about books we were reading. I told her about In Defense of Witches. Once again, I told her that I didn’t think I wanted kids. This time, with her grandkids in the house, she accepted it. She even made the profane confession:

“Growing up, I was like your aunt. I never pictured myself wanting children.”

As she left the room to check on Eli in his cradle, and return to the kitchen to start cooking dinner for the family, I basked in the rare acknowledgement that if my sister and I didn’t exist, my mom would still have a fulfilling life. Just like her younger sister does, the one who always goes to the movies with her husband on Halloween rather than stay home to give candy to kids because they deserve a treat, too.

When my sister returned on Friday, her kids ran to her. She took Eli in her arms and Noah clung to her leg. I felt a hollowness in my chest. Noah demanded she read him a story – nobody else, he wanted Mommy to read it – and as I noticed this sudden physical longing to snatch them up, I could understand wanting my own children. I marveled at my body’s peculiar witchcraft, a stirring of hormones and heartbeats for me and me alone.

Katherine Varga is a writer and theatre critic living in Rochester, NY. Her plays have been performed in 8 states. Her creative prose has appeared or is forthcoming in Passengers Journal, Qu Literary Magazine, Arasi, The Evermore Review, and The Paper Crow.

Delta N.A. (@delta_na) are a couple in life and art, working together by painting in unison. They learn from each other and share a creative flow poured into their artworks, a common language that makes each artwork realized by two pairs of hands look like a single artist’s creation. In love and collaboration they find the key to face and accept differences, crumbling the boundaries separating human nature from freedom. The artworks signed by the duo are present in numerous public and private collections and have been exhibited in solo and group shows across Europe, U.S.A., and Asia.