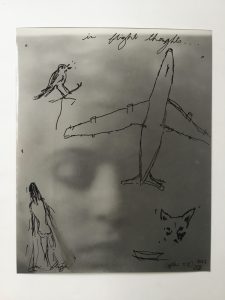

by Grant Beran

The Time I Evaded An Unwanted Marriage Proposal

Sura K. Hassan

There’s a photograph of me, aged eighteen months. My mother dressed me in the crimson pink dupatta and the blouse of her wedding dress along with the jewelry, from the heavy golden necklace she’d worn to the big pearl earrings my grandfather had gifted her. My hair’s done up in a Diane-esque hairstyle, complete with red lips and dark eyes.

Growing up, I detested this picture while my mother, grandmothers, aunts, and older cousins all smiled gleefully. “Any day now,” they’d say, and I’d swear it wouldn’t come to that.

After all, who gets married at sixteen in the twenty-first century?

The women in my family, apparently. Even though my cousin’s marriage to her long-term boyfriend at twenty-nine caused quite the scandal in the family, it never truly reached the level of accelerated modernity I had hoped for. After all, immediately after the affair, the news of cousins, a mere year or two older than me, tying the knot spread. Jasmine’s victory at a “late” marriage seemed to have encouraged the rest of the family to correct themselves. No longer were girls allowed to pass the late age of twenty. If you were old enough to get a driver’s license, you were old enough to have a child.

Yet, between my academic achievements and science competition-winning streaks, I’d sincerely hoped that my mother wouldn’t set her eyes on me. When sixth form came by, along with a scholarship, I took a deep breath. Surely, my mother wouldn’t want me to get married if I was doing well at school. Right?

Unfortunately, even the heavy burden of giving five A Level subjects wasn’t enough to deter my mother. As I traveled around the country, winning competitions and establishing my ground in the attempt to woo an Ivy League university, my mother was sharing the rare picture of me dressed in our traditional attire, looking distinctly feminine and not me.

So busy was I with my academic and extracurricular activities that I failed to notice the gradual change in my wardrobe. My predominantly black wardrobe of hoodies and ripped jeans was slowly replaced with flowery kameezes. When I came from school one day to see that my favorite Enrique Iglesias limited edition sweatshirt was missing, I knew something was amiss.

My sisters were called into my bedroom, and we spent the next few hours rummaging through my wardrobe, trying very, very hard to disprove the obvious. “You guys need to keep your ears open,” I told them as we made a solemn pact to ensure that neither of us got married before our twentieth birthday.

Months went by, but we heard nothing. I almost lulled myself into a false sense of security when it happened. Two days before my departure to Lahore to participate in the Intel ISEF National Competition, my sisters pulled me into our study.

“You’ve got a rishta,” my youngest sister, Masooma, informed me.

“The proposal’s from one of Mumma’s friends’ nephews,” Abeeha told me.

“What?” I was surprised. Having passed my sixteenth and then seventeenth birthday without any mention of a proposal, I thought-

“He’s an electrical engineer in Melbourne,” Masooma went on, “I heard Khala Amma and Mami talk about it.”

“Mummy’s seriously considering it,” Abeeha continued, “she says it’ll be good for you. She says you can study aerospace engineering in Melbourne.”

“What?” I was at a loss for words. “How?”

“The family’s quite affluent. The boy- well, man, he’s twenty-six- went to Australia for his undergrad and got a job there,” Masooma relayed the story with the precision of a gossipmonger who could only be born out of the socioeconomic environment of our family. “His family immigrated last year. He’s going to finish his graduate degree in May, and they want you to get married in July, just in time for your graduation.”

“What?” I repeated once more. “I don’t plan on going to Australia. I haven’t thought about-”

“They’re coming to see you on Saturday evening,” she cut in. I felt the air knocked out of my lungs. This wasn’t part of the plan. I had never, ever thought of Australia, much less marriage.

“On the bright side, he’s offered to pay for your education,” Abeeha piped in.

That seemed to do it. I regained my composure and narrowed my eyes. “If I get married, you’re next,” I hissed and watched the color leave her face.

“What? No!” she howled, and I snickered.

Then, it came to me.

“I have a plan,” I whispered, and the three of us stepped closer. The next day, I found myself in my head teacher’s office, informing her of the situation. “But- but you’re just seventeen!” she exclaimed in horror. “What about your education?”

I sighed. One of the downsides of studying at the most prestigious school in the country was the collective assumption that everyone there was going to achieve academic excellence. Even though most girls in Pakistan do end up getting married before the age of eighteen, in the metropolitan city of Karachi and my immediate social circle, thanks to my school, the practice is considered archaic. Taboo, even. Girls married fresh out of A Levels had often been treated as social pariahs. Granted, there had only ever been one or two cases in the senior years. Still, when you’re the only person in your senior class in such a situation, you tend to attract quite a bit of sympathy.

And that was precisely what I was counting on. As I collapsed into the chair closest to my teacher’s, I thought of everything in my life that drove me to tears: people comparing Stephen Hawking to Albert Einstein (he’s a great scientist, but he’s not on the same level as Einstein), Enrique Iglesias renewing his relationship with that tennis player, my father’s outright refusal to let me be a pilot and NASA’s policy of only hiring American citizens. When that didn’t work, I vividly imagined a rejection from MIT and the floodgates opened. My teacher was horrified.

“Please, Miss,” I pleaded between my hysterical sobs, “I can’t go home on Saturday.” And that’s exactly what my dear teacher did. Instead of coming home on Saturday afternoon, my teacher rescheduled our flight to Sunday morning. It was perhaps the most self-indulgent week of my life. After the competition was done for the day, our teacher would take us around the old city, and my competition partners would treat me to Lahori treats unavailable in Karachi. We even went on a shopping spree to calm my nerves. I’d never experienced shamelessness before that day, but at that moment, as everyone fawned over me for something other than my academic achievements, I felt decidedly shameless. And I loved every moment of it.

#

Back in Karachi, my sisters had begun the second phase of our plan. All texts and information pertaining to the change in my itinerary had been deleted. Only Abeeha and Masooma knew when I was really coming home. Everything was set. My sisters were secretly delivering me morsels of information about the proposal. That evening during tea, when the adults retreated to my grandmother’s bedroom to discuss the intricacies of the meeting with the man’s family, my sisters stood outside the door, listening to the conversation.

“Masooma will make the tea,” Khala Amma said, “and Sughra will take it to his family. I’ve taken out the blue porcelain set for the occasion. Toto, make sure that Sughra doesn’t wear anything too overwhelming that would cause her to slip and drop the tray.”

“Don’t worry, baaji,” my mother assured her, “I’ve picked out the khushali kameez for her.”

“The father’s still in Melbourne,” my youngest uncle advised, “so you ladies better do the talking.”

“Who’s coming to see her?” my eldest uncle’s wife, my Mami, asked.

“His mother and his sister are,” Khala Amma informed her, “and their eldest phuppi.”

“I don’t like the phuppi’s involvement,” my mother chimed in, “I’ve already had a tough time with the girls’ phuppis. I don’t want her to have a hard time like me.”

“Don’t worry. The phuppi’s in Karachi. Only the boy’s immediate family is in Melbourne,” Khala Amma continued. Unfortunately for my sisters, we never got to learn more. At that very instance, our youngest uncle’s wife, our Choti Mami, entered the hallway.

“What’re you two doing?” she questioned my sisters.

“Nothing,” they said in unison and knocked on the door, putting an end to all talks of the match. The next day, my sisters woke up to the sound of my Khala Amma yelling at the household staff. Bed sheets were changed for the designer ones, all our finest cutlery and china were taken out and washed, the furniture was dusted and then dusted again, and the chandelier in the formal sitting room was polished to perfection. In the kitchen, our chef prepared an abundance of savory treats and sweet delights. My grandmother oversaw the baking of our famous nankhatai, an almond sugar cookie whose recipe was perfected in the court of the Mughal Emperor Akbar himself (or so she claims). Our gardener was mowing the lawn, picking the best tulips and roses from our garden to put as the centerpiece at the dinner table. Our driver was running errands all around the city, getting mithai and other assorted delicacies from Decca Sweets, nimco from Nimco Corner, and rose water from Saeed Ghani to brighten my skin and achieve that innocent, dewy look that is considered to be the epitome of beauty and youth in our part of the world.

By the time lunch rolled by, my mother was very concerned. I had not called her at all. As per schedule, I should’ve called her by then, requesting the driver to pick me up from the airport or one of my fellow competition goer’s houses. When the clock struck two, my mother finally turned to my sisters, who were oddly silent while scarfing a whole plate of biryani.

“What time is your sister coming?” she asked them. Without skipping a beat, Masooma spoke up.

“She’s coming tomorrow at one. Why?”

The expression on my mother’s face, I’m told, was one for the history books. She was stunned for a moment, followed by disbelief and then denial.

“We thought she was coming today!” she exclaimed, causing my sisters to shrug.

“She was always coming tomorrow, Mummy,” Masooma added. When the realization hit her, I was later informed; there was a momentary bout of silence. Even our rowdy cat, Mica, who’s in the habit of disrupting meal times, was quiet.

And then-

“This girl doesn’t tell me anything!” My mother wailed, rushing out of the dining room. In the distance, they heard plates clattering, followed by our Khala Amma’s cry.

“Batao zarra!”

Then, an emergency session was held in my dear grandmother’s house. This time, my sisters were more successful in listening to the entire conversation.

“Didn’t she say Friday?” Khala Amma wanted to know.

“I always thought it was Friday,” Mami confirmed.

“Yes, it was definitely Friday,” my eldest uncle, our Mumma, agreed.

“So, how did we get the date wrong?”

“Perhaps the girls are confused,” offered my Choti Mami.

“But the boy’s family is coming in an hour!” announced my grandmother.

My sisters had to make a run for it as the adults marched out of the room, making the necessary changes. Chaos erupted in our household. My Khala Amma walked about the entire perimeter of our house as she tried to explain to the boy’s family that they couldn’t possibly come over today; the intended bride was in another city.

My grandmother was in the kitchen, instructing our overworked kitchen staff to make a less fancy variation of the treats they’d spent all day preparing. As my mother frantically rushed up the stairs to somehow contact me (my phone was switched off, as it always is whenever I’m asleep), my sisters settled into the kitchen stools, munching on nankhatai. If the boy’s family wouldn’t eat it, they would. “What’s wrong, Nunna?” Masooma asked our grandmother, who sighed in defeat before sitting with them.

“Your mother and Khala have no idea how to handle these things!” she grumbled before grabbing a cookie for herself as well.

#

Ultimately, my would-have-been husband’s family came home for a lovely little tea party. They loved our house, loved the garden and what we’ve done with the patio, as well as how much our household staff seemed to love and respect us. My sisters tell me that they were particularly taken by a photograph of me that had been provided to them by some matchmaker. Still, regretfully, they couldn’t revisit us. They had a flight to Melbourne in two days; they had only come to Pakistan to see me. Unfortunately, my commitment to my education had created a bit of a wedge between our families, even before they’d met me. So, as much as they liked the idea of an educated daughter-in-law- a bahu, as we call it in Urdu- it was clear to them that my priorities were elsewhere.

My mother was devastated at the loss of such an amazing marriage proposal. But my sisters say it took her twenty minutes to recover from the blow, instead focusing on how my would-be mother-in-law’s eyes kept drifting towards our chandelier.

“They must be one of those people,” she would later say to Khala Amma, who nodded immediately. “Probably think we’re going to hand them a big dowry.”

“And the way they looked offended when they found out that Sughra was in Lahore!” Khala Amma agreed. “Those people were never going to let her study.”

“They’re probably just modern on the surface,” my Mami provided her insights.

Overall, by the time I returned to Karachi, my entire family was convinced that the date mix-up was divine intervention. As I showed off my award to the rest of my family, I swear I caught my grandmother and mother tearing up in relief. If it weren’t for my inside knowledge of what had transpired a few hours ago, I would say that my mother was proud of me. But later that evening, after the adults were all asleep, while my sisters and I smoked a cigarette on our balcony, we decided that proud or not, our mother should be happy that she’d raised three resourceful girls. If we could get out of a marriage proposal, we could get out of any jam in life.

Sura K. Hassan is a technical writer from Karachi who lives, works and studies in Istanbul. Her work has appeared in The Minison Project. Find her on Twitter: twitter.com/notsurakazan.

Grant Beran is interested in exploring what a photograph can express and finding ways, through experimentation, for this expression. He has been working with photography since he was thirteen and began exhibiting in 1985, aged 17. From the beginning, he has had an experimental approach to photography. Drawing equally from art-historical and contemporary influences and aspects of pop culture, such as music and fashion, he has exhibited widely in solo and group presentations throughout the world including New York, London, Paris, New York, Japan, China, Sydney, Melbourne and New Zealand. His photographs are in private collections around the world.