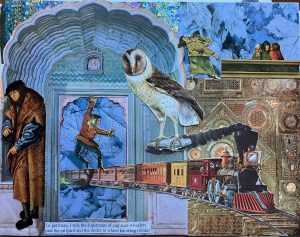

Where Knowing Resides by Devon Balwit

Newton’s Orbit

Tarik James Ghiradella

It was in a place where silence had weight and memory was conditional. Sometimes it went missing without a sound. But then he saw it again. A small, pulsing blur near the edge of the belt. Moving just enough to notice.

He adjusted the lens. Logged the position. Faint. Faster than last week. Different. Inside, a light blinked on. Then off. She was awake.

He hadn’t named it after her. Too obvious. Too much like begging for a miracle. Or worse—a sign. But sometimes he wondered if it knew her name anyway.

He waited, but she didn’t come to the door. Didn’t call his name.

Last year she’d sit with him on clear nights. Wrapped in the quilt her mother made. She’d name the stars wrong on purpose, just to make him laugh. Now she wandered. Mostly inside. Sometimes out.

He’d found her barefoot in the snow once, looking up, whispering under her breath.

The object blinked again. JD472-b. He had cataloged it before she started fading. It had strayed slightly from its pattern. Suddenly un-anchored, as if it had forgotten what it was.

He scribbled a note beside the coordinates. Then scratched it out, looked back through the lens and then again at his notes. The numbers kept shifting. Faster. And that was wrong. Movement like this should take months, even years. Not days. Not like this. It should have been steady, predictable. Yet each time he returned to the lens, the rock had stolen another fraction of speed—sliding closer to the rim, as though some hidden hand were tugging it outward.

Frost curled up the deck rail, the boards silvering under the moon. His breath clouded the eyepiece as he leaned in again. Still there. Dimming. Speeding away. Wobbling just slightly.

He heard the rustle of her slippers on the kitchen tile. The light switched on again.

“Can you turn it off, please?” he said, his eye still fixed to the scope. “I need it as dark as possible.”

It was almost too faint now. Falling up and behind the belt, like a child slipping out to the yard when no one noticed. Still visible. But barely.

He reached for his pencil, then stopped. Let his hand rest above the page.

In the quiet, he thought of the first time he saw it. Late October. She’d been falling off to sleep on the couch, a candle burning on the sill. The scent of cedar and wax.

He’d shouted then. Loud enough to wake her. Loud enough to feel like something had been discovered, named and claimed.

She woke and smiled, got up and walked out to kiss him on the cheek.

“What is it?” She whispered, her voice so soft and delicate. “You found something?”

He just nodded, eyes still fixed on the lens. She waited but after a moment went back inside. That was before the forgetting. Before he stopped calling out.

He picked his hand up off the notebook, leaned back and peered to his side.

She stood in the doorway now, quilt around her shoulders.

“You’re still out here?” she said.

He turned and spoke calmly, as if talking to a toddler. “I’m tracking something.”

Her eyes found the sky. For a moment she looked like herself again. The half-smile. The reflex to play.

He waited for her to call Orion “the saucepan,” or to insist the Pleiades were “just a bunch of scattered crumbs someone spilled.”

Instead, she said: “It’s drifting, isn’t it? You can see it but you can’t stop it.”

He froze. He hadn’t told her. She couldn’t know.

When he looked up, she was already walking back inside. Only a faint warmth remained where her hand had rested on the rail.

* * *

Three rows out he cut the engine and stared into the woods. Not because there wasn’t a space closer, but because he wasn’t ready to walk through those doors just yet. He sat and thought.

The doctor, he remembered, had said the word last week. Softly. As if laying down a folded blanket: “Have you thought about hospice?”

He nodded like he understood. Like they were just talking next steps. But the truth was, he hadn’t heard much after that. Just the hum of fluorescent lights and the way his wife sat quietly staring down at her shoes, as if she already knew.

Hospice. It echoed in his ears. It lingered and thinned leaving only the woods and space in front of him.

But today wasn’t a decision. That’s what he told himself. Just information. Just learning.

Inside, the air smelled of hand sanitizer and wood polish. A small fountain burbled in the corner. A bowl of peppermints sat by the sign-in sheet.

The woman at the desk had a soft perm and a voice like a nurse who loved to sing.

“Is this for your mother?” she asked, reaching for a clipboard.

He shook his head. “No. It’s for my wife.”

That gave her pause. Her hand stilled. Something flickered in her eyes—surprise, sympathy, recalibration.

“Of course,” she said, and offered him the clipboard.

He sat, staring at blanks: Diagnosis (if known), Mobility Level, Allergies. The pen didn’t write at first. He pressed harder until the tip tore the paper. He thought of her handwriting, her lists on the fridge—neat rows of groceries and errands. He couldn’t imagine her name on these lines.

A moment later, he slid it back across the desk, empty. She looked at him carefully.

“Okay.” She said, “Then would you like to sit down with one of our nurses? She can walk you through what care here would look like.”

“Not today, I’m sorry.” He said quickly. “This was just … to see what it involves.”

She nodded, though her eyes lingered. “I understand. We’re here whenever you’re ready.”

In the hallway, someone was humming Frank Sinatra. A door opened, and he caught a glimpse of a bed, a tray of untouched soup, a woman staring at the ceiling. He looked away quickly.

Three Coins in a Fountain, he thought.

He didn’t stay long. Just enough to say he’d come. Just enough to tell himself it was premature. When he got up to leave, the peppermint bowl was still there, waiting, as though it hadn’t noticed anything at all. He folded the pamphlet before reaching the car.

* * *

He had first logged JD472-b five years ago. A minor Kuiper Belt object on a slow, erratic path beyond Neptune.

Most of the rocks out there moved like clockwork, locked in ordered resonance with the outer planets. Tugged predictably by gravity and time.

But this one kept sliding. Not wildly. Not alarmingly. Just… off. As if nudged once, long ago, and never corrected.

Some will blame Neptune’s interference, he thought. Others will whisper Planet Nine, that brute hiding in the dark, exerting invisible force.

Or maybe it was venting. Trace gases shifting its aim, too faint to see, just enough to matter. He didn’t know. It didn’t matter.

He only knew that every so often JD472-b blinked where it shouldn’t. And once—only once—it disappeared entirely. Not gone. Not vanished. Just…unaccounted for. As if space had swallowed it, then released it again.

He’d watched it for years. Not because it was important, but because it wasn’t. Because it behaved like something fragile. Because even out there, past the maps, something could still slip.

That night, he stayed at the telescope until his eyes burned. It didn’t return. The scope gave him only stars in their endless obedience, sharp as nails in the black.

Inside, the kitchen light flickered on again. He didn’t call out. Didn’t ask her to turn it off. He only sat there. Waiting. Just in case. Because sometimes, things come back around.

Tarik Ghiradella is a composer, drummer, and storyteller whose work bridges sound and narrative. A graduate of the Manhattan School of Music, he has recorded for Grammy-nominated artists and co-hosts The Composer’s Studio podcast, where he explores the creative lives of fellow artists. Newton’s Orbit marks his debut as a fiction writer.

When not making art, Devon Balwit walks in all weather and edits for Asimov Press, Asterisk Magazine, and Works in Progress.