By Matthew Liptak

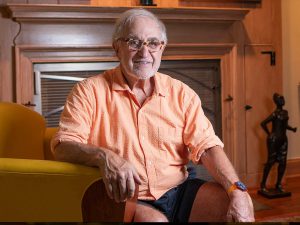

When he graduated from UBalt Law, Chris Sweeney, J.D. ’16, knew he wanted to serve the public, but he didn’t know that becoming workforce development manager at Maryland Volunteer Lawyers Service (MVLS) would lead him to a niche of the law that would be so rewarding: expungement.

Expungement is the legal process of removing the public record of someone’s involvement in a criminal matter. The records don’t even have to result in a conviction, they just have to involve law enforcement. Eliminating records may sound like a simple task, but it’s an act that can have far-reaching impacts on the lives of those who are exposed to public scrutiny.

“I didn’t know I was going to get into being an expungement guy, but I very quickly became passionate about this work because I saw how much it means to people,” says Sweeney. “To erase something that has been a stigma to them, and a ghost of something they did in the past – I’ve seen a lot of people get very emotional getting these forms signed, thinking, ‘This is finally gone from my life.’”

Sweeney says at least 80 percent of his work at MVLS involves expungement. He regularly makes presentations at Baltimore job-training sites, educating people on their legal rights. Many of those attending are formerly incarcerated individuals who are working to find a job or better housing. Public criminal records, which come up in background checks, can be a barrier to a better life for them.

He usually spends 10 to 20 minutes in person with his clients. The expungement petition is prepared beforehand, so they only need to confirm some vital information and sign it. Occasionally a prosecutor or judge may have questions or objections to the petition, which is normally taken care of in a court hearing.

“I think expungement is immensely important,” says Angus Derbyshire, J.D. ’14, director for pro bono at Maryland Legal Aid, the largest provider of free legal services in the state. “There’s a whole racial justice component to this, too. We have to be cognizant of the fact that we have overpoliced our Black and brown communities for so long.” Maryland Legal Aid offers regular expungement clinics throughout the state.

Michael Christopher Stone, J.D. ’13, is director of pro bono programs at the Homeless Persons Representation Project. Expungements are a large part of the workload for the roughly 400 attorneys, law students and paralegals who work for the organization. Like many other UBalt Law alumni, Stone is passionate about helping people in need.

“Every time expungement opportunities expand, we’re getting closer and closer as a society to recognizing that you can’t saddle someone with the ‘Scarlet letter’ forever, and still expect them to continue in society,” he says.

New laws make expungements easier

Expungements are expected to increase in Maryland. Thanks to Maryland’s Senate Bill 201 of 2021, many public criminal records will be automatically cleared by October 2024. And Maryland residents with cannabis possession convictions are now eligible to have those records expunged, now that simple possession of cannabis is legal in Maryland.

Stone said SB 201 will lead to much more work for attorneys. Expungement law has become much more complicated in recent years, as opportunities for the expungement process have grown, he says. [View a May 2023 training video on criminal record expungement in Maryland.] But he appreciates the new lease on life SB 201 offers to many Marylanders.

“It’s the only automatic expungement in the law, and it was hard-fought for,” he says.

In addition, as of Oct. 1, 2023, waiting periods shorten for filing a petition to expunge certain conviction records, including those for cannabis-related convictions. Under SB 37, known as the REDEEM Act of 2023, waiting periods for filing expungement petitions for a conviction eligible for expungement under § 10-110 of the Maryland Criminal Procedure Code are halved. This means the new waiting period is five years for a listed misdemeanor in general (formerly 10 years) and seven years for a listed felony in general (formerly 15 years).

To all three of these UBalt Law alumni, the expansion of expungement means the growth of justice in Maryland’s evolving legal system.

“People call it a second sentence, or a ‘street sentence,’” Sweeney says of public criminal records. “We always say people have to pay their debt to society. This person has done that. They’re still living with this record.

“I think that people should not be defined by the worst things that they’ve done, for the most part. Regular folks mess up and they can change. I absolutely believe that. People deserve a chance to succeed, so I think of clearing records as an investment in that person.”

Matthew Liptak writes from Severna Park, Md.