Retired Judge Richard O. Motsay, J.D. ’52, didn’t know he was starting a dynasty when he graduated from UB Law 68 years ago.

For starters, four of his eight surviving children earned their law degrees at UB. And it didn’t stop there. The latest Motsay to graduate from UB Law is his grandson, Philip Motsay, J.D. ’16.

While the Motsays aren’t alone among multi-generational families of UB Law alumni, they lead the pack at three generations.

How does the judge, now 95, explain it?

“I wanted to be a lawyer since I was in third grade,” says Judge Motsay, who retired from the District Court of Maryland for Baltimore City in 1995 (and continued sitting in senior judge status until 2013). “I guess the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. I took my children to the various jobs I held, and we’d talk about it at dinner while eating spaghetti and meatballs.”

The judge’s oldest daughter was the first to follow in her father’s footsteps.

“When I was in college I helped him in the State’s Attorney’s Office, interviewing women held in pretrial detention,” says Rosemary Motsay Ranier, J.D. ’76.

Like her father, Ranier attended law school at night while working full-time as a law clerk in the Maryland Office of the Public Defender. After passing the bar, she served as an assistant public defender until retiring last year.

James W. Motsay, J.D. ’81, an independent administrative law judge in Baltimore, was the next family member. “I’d say, what choice do I have?” he quips. “I was never pushed by my dad. But he did say to consider it.”

Not that he needed a push. “I had been a deputy clerk in the city courthouse before law school. All the attorneys said to hire a UB graduate as a trial lawyer. And I wanted to do trial work.”

The third generation, Philip Motsay, J.D. ’16, is an assistant state’s attorney in Baltimore County. While growing up, his plans never included following in his father’s and grandfather’s footsteps.

“After graduating from college, I was looking for something that would give me multiple career opportunities and decided on law school,” Philip Motsay says. “I applied to UB first — after all, it’s a family tradition. But before I could send applications to other law schools, I got accepted. So I figured, this is the place to go.”

MEET THE MOTSAYS

The Motsay clan’s devotion to the University of Baltimore goes beyond the law school. Here’s the complete list, including other family members who went to UB and earned different degrees.

- Judge Richard Motsay, J.D. ’52

- Rosemary Motsay Ranier, J.D. ’76

- James Motsay, J.D. ’81

- Sharon Tobin, J.D. ’88

- Patrick Motsay, J.D. ’89

- Philip Motsay, J.D. ’16

- Lucy Rutishauser, MBA ’87

- Joan Brown, MBA ’91

- James P. Motsay, B.A. ’10

Other alumni families shared similar reasons for choosing to carry on the UB Law tradition.

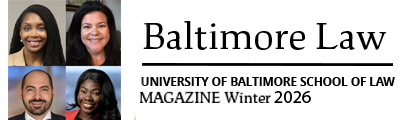

Marilyn Harris-Davis, J.D. ’83, has worked as a Baltimore media and political strategist since earning her law degree. “UB has always been service-oriented,” she says. “It’s where I came to understand the importance of legislation.”

From working on the political campaigns of retired U.S. Sen. Barbara Mikulski and former Baltimore Mayor

(and later Governor) Martin O’Malley, Harris-Davis served in roles as varied as legislative aide, director of Baltimore’s Office of Cable and Communications, and director of the State Office of Cemetery Oversight.

“It’s the nature of service that I learned at UB Law,” Harris-Davis says. “My son Marrio and I both went to Friends School, so we had a service-oriented mentality. But I always told him, you can’t go to law school for me. You need your own reasons.”

Her son, however, had been indoctrinated in politics, starting when he and his older brother were carried on their mother’s hip during political campaigns, Harris-Davis says. Law school was a natural choice. But which one?

“The fact that I’m from Baltimore, live in Baltimore, and my parents are from Baltimore is the reason I chose UB,” Marrio Davis, J.D. ’19, says. “It was also a draw that my mother went there.”

He now works at the Baltimore County state’s attorney’s office while waiting for his bar exam results.

‘A Sense That I Belonged’

Margaret A. Mead, J.D. ’89, was 29, a mother of two and married to an Air Force officer when she began applying to law schools.

“I felt like I fit in better at UB,” Mead says. “There was a sense of camaraderie, not cut-throat competitiveness. I had a sense that I belonged.”

Her law school experience also instilled an awareness of right and wrong, which launched her career as a criminal defense attorney.

“I love the practice of law,” says Mead. “I don’t know that I would have had the success I’ve had if it weren’t for UB — especially Professor Byron Warnken. He helped me get my first clerkship that led to so many other things.”

Her son, Brandon Mead, J.D. ’09, is a partner in his mother’s criminal defense firm.

“Brandon was seven when I started applying to law schools,” Margaret Mead says. “‘Mom, you can do it,’ he told me. I took him to classes a couple of times when I couldn’t get a babysitter.”

UB Law prepares future lawyers for the real practice of law, Brandon Mead adds: “All the supports are there, like mentorships. It’s a challenging place, but ‘good’ challenging if you’re willing to do the work.”

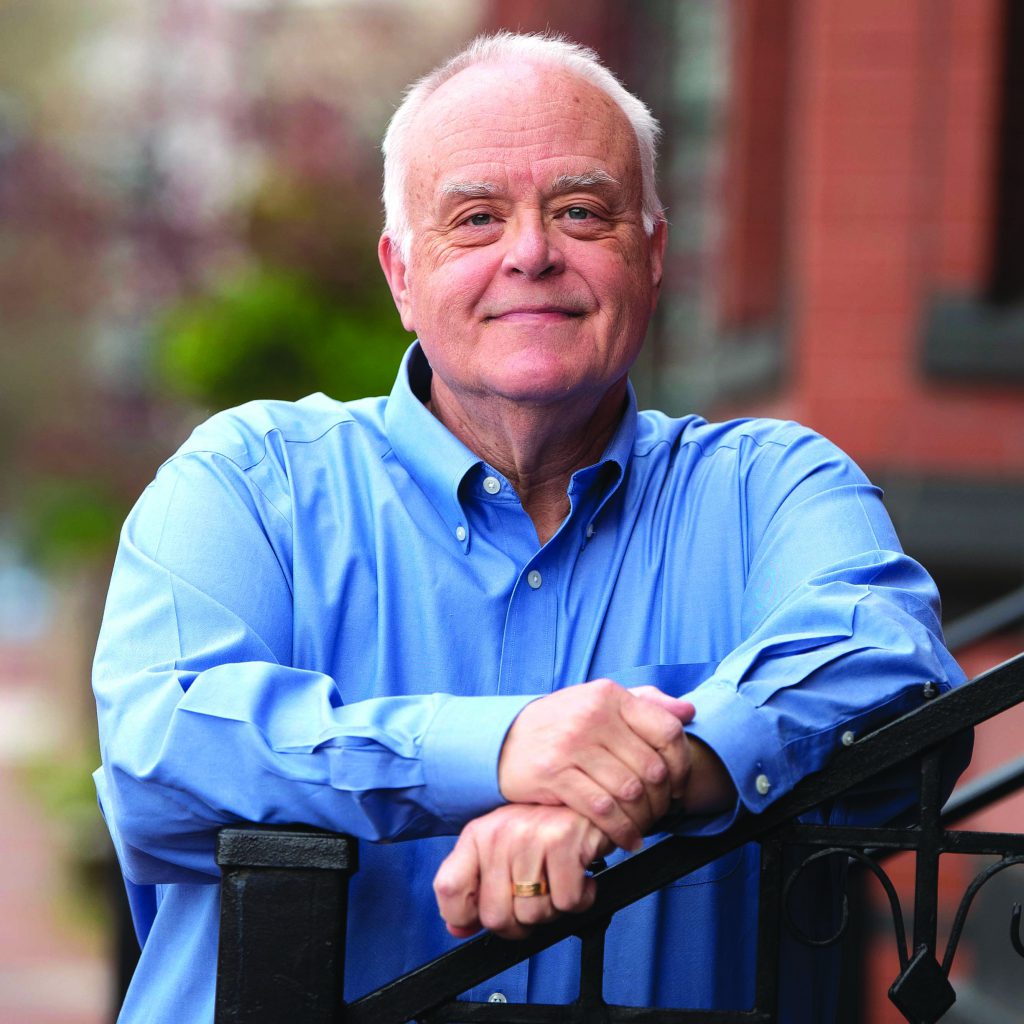

Barry M. Chasen, J.D. ’80, remembers when he first wanted to be a lawyer. “By about age 12, I had read 40 Perry Mason novels,” he recalls.

Yet his parents’ modest background — his father had an eighth-grade education and drove a cab — meant there was no money for college. “I started working full-time and went to school at night,” Chasen says. “Then I got admitted to UB Law. It was a great experience.”

He was nearly 33 when he started practicing law. Almost 40 years later, the firm he founded employs 26 lawyers.

“I realized if I take care of the clients, money takes care of itself,” Chasen says. “It’s one of the firm’s core values. My opportunities at UB Law changed my life and gave me the opportunity to do something I like.”

Chasen’s success allows him to give back and to help others from modest backgrounds. His philanthropies include the World Central Kitchen, So Others May Eat and UB Law’s clinical program, to which he and his wife Lyn recently made a very generous gift. “We support these causes because there’s a lot of injustice in the world,” he says.

His son, Ben Chasen, J.D. ’14, remembers wanting to be a superhero as a kid.

“As I got older and started understanding what my dad did for a living, I saw that he was helping people, which is what a superhero does,” he says. “But I distinctly remember my dad not pushing me toward law.”

The realization in college that doctors and lawyers are the most powerful people in society made Ben Chasen think about law school. “I wanted to practice locally, so UB Law was the way to go,” he says.

As a practicing lawyer, he keeps in mind his father’s sayings about the profession. “Especially, ‘It’s not the perfect of law, it’s the practice of law,’ he says. “It keeps me focused.”

Joe Surkiewicz is a writer based in Baltimore.