Much of the early work of the firm was learning by experience and bootstrapping. Silverman’s first real civil case was on behalf of a guard at the courthouse whose son died in a tragic accident. He figured out how to prepare the case and recovered damages for the client. If he ended up in a case where he was out of his depth, he would read a book or take a weekend seminar — and then call the instructor with questions.

“For years, we called ourselves ‘the firm with no adult supervision,’” he quips. “We work hard but we try to be human about our hours. We don’t tolerate jackasses or people who don’t play nice in the sandbox.”

That sort of straight talk is what distinguishes Silverman. Kathleen “KC” Murphy is director of the criminal division in the Office of the Attorney General for Maryland. She’s known Silverman since the ’90s, when she was a law clerk in Baltimore City and he was a public defender. Since that time, they’ve had cases opposite each other, most recently in her role as an assistant attorney general.

“As an attorney, Steve is consistent, he’s a straight shooter who gets to the real issues and cuts to the chase,” she says. “He’s always collegial and a pleasure to work with, even when we disagree,” she continues. “In the courtroom, his style has always been more charm than bluster, and he’s professional and respectful of everyone in the courtroom. He doesn’t need to demean people to be assertive.”

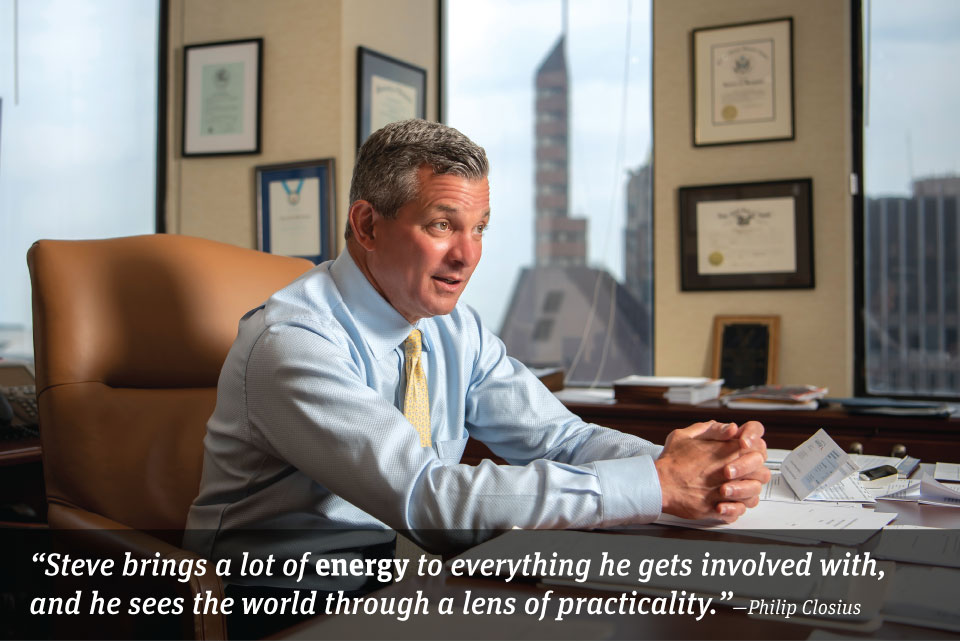

As dean of The University of Baltimore School of Law from 2007 to 2011, Phillip Closius appreciated Silverman’s keen insight as a member of his advisory council, particularly when Closius was securing funds for the new law school building.

“Steve brings a lot of energy to everything he gets involved with, and he sees the world through a lens of practicality,” says Closius.

Now a professor at the law school, Closius is of counsel at STSW in the area of sports law. He’s closed a case against the National Hockey League related to concussions, and he continues to work on a case against the National Football League on the abuse of prescription drugs. Closius says the humane hours and collegial atmosphere at STSW are real and come from the top down.

“Steve has something I try to talk to my law students about,” says Closius. “It’s good to be a good lawyer, but you need to be personable to appeal to a jury and to get clients. You can relate to Steve as a person, not just as a lawyer.”

In 2016 Silverman founded the Silverman Thompson Slutkin White fellowship for first-year law students at The University of Baltimore. The inaugural recipient, Greg Waterworth, J.D. ’18, says the fellowship was a unique opportunity to work directly with Silverman and other partners.

“A lot of opportunities for law students early on are ‘safe’ or administrative. It’s a coddled experience,” says Waterworth, now a litigation associate at Saul Ewing. “[At STSW] you were treated as a member of a team, so you got over any fear of the unknown and realized that if you don’t know something, you can learn it. I was treated as a colleague, not an intern.”

Ethan Nochumowitz, J.D. ’14, had a position as a law clerk at STSW in 2012 and is now an associate there. He explains that the partners select their associates based not only on their GPA, but also on whether they will fit into the culture of the firm, which Nochumowitz says is very much directed by Steve and very much outside the norm of a typical firm.

“It’s not high-stress. You’ll see Steve skating around on his skateboard in the office, and associates are encouraged to plan events like pool parties and ping pong tournaments,” he says.

Yet the experience of a young lawyer at STSW is not all fun and games.

“Steve got his start in the public defender’s office, and that shaped his view on shaping young lawyers,” says Nochumowitz. “He was thrown into court, and he believes the best way to become a savvy lawyer is to be thrown into the ring. [The partners] make it a priority that you get substantive experience early on. You’re not sitting in a cubicle doing research.”