The past year has been a pretty good one for cinephiles. Not great. But good. While the caliber of movies coming out of Hollywood is on average very, very, very low (and yes I did need three verys. Did you see Battleship? No? Good. Hopefully you like yourself more than that), the big movie houses still producing a lot of what resembles repackaged, empty calories than anything worth the mind to think about ten seconds after the credits. Yet there have been enough inventive and affecting foreign and indy movies to give some sliver of hope that culture, especially US culture, hasn’t once and for all fallen into some dark and strangely reflective pond, happily swimming in their own narcissism and consumerism (which are pretty much the same thing). And while some of these good art-house/indy/foreign movies have gotten some small dose of praise (The Master and Beasts of the Southern Wild, two truly excellent films, were both nominated for Best Picture), there have been a few others that have flown a little low of the media hype machine.

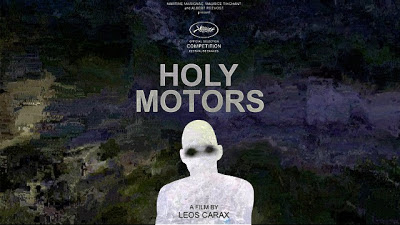

Holy Motors is one such movie that has been passed over not just by critics and award committees, but by

the public as well. I will warn you here: it is not a movie that everyone will like. It has no over-arching

narrative (per say), and at times doesn’t even make logical sense. The main character, Monsieur Oscar, is not even a typical protagonist (or antagonist). He is no one really. At the beginning of the movie we see him leaving for a day’s work, seen off by his wife and kids. To apply the normal kinds of symbolic interpretation to this film seems unreasonable. True enough, he is going on a journey. But that doesn’t make this a prototypical quest or pilgrimage movie. Even Oscar’s leaving home seems peculiar. He walks down a long driveway in suit and tie, away from his large, blazing white modernist home, waved on by wife and kids, followed down the driveway (very slowly) by a BMW flanked by two men both with some kind of large machine gun. Why doesn’t Oscar get into the car? What kind of procession is this? Down the street he finally gets into another car, a limo, and from there moves on to his “appointments.” His appointments are more like roles. He plays actor to real life. His limo acts as backstage where he changes into character. An old gypsy woman begging for change in Paris. A troll who eats the flowers in graveyards and steals fashion models from photo shoots, carrying them without protest or noticeable emotion into the sewers. He plays an old man dying in a hotel. A mobster. An motion-capture actor for video games who flips and swings and runs in front of a screen that couldn’t be a setting anywhere, even in the fictional world of video games. All of which is visually stunning and absolutely absurd.

A brief suggestion: Don’t tear your hair out over meaning. It will probably come from seemingly nowhere, in little blips and drops. Things like, “Oh, so this is some kind of manic, rambling comment on commercialism,” or “Maybe he’s saying something about voyeurism, about social media, about masks and contrived personas, about exhibitionism and … What? … I don’t know.” Be assured, your brain will short circuit if you try to intellectualize this movie too much.

But, if you must find a meaning in the chaos, my advice would be to keep it simple. Something like: This movie is a movie about movies. It has something to do with repetition, with movement, with the photographer who found out that horses float a little when they run, with the restrictions of a frame, with watching a movie, with habit and loops and what is beyond them.

Samuel Beckett said once, “Habit is the ballast that chains a dog to his vomit,” and this is a movie that does really cool things with that chain.

By Adam Shutz

**All the movies mentioned above (except Battleship) are available at Langsdale.